NASA's Juno spacecraft has been getting closer and closer to Jupiter's volcanic moon Io with each recent orbit. Juno is in its 57th orbit of Jupiter, and on December 30th, Juno came to within 1500 km (930 miles) of Io's surface. It's been more than 20 years since a spacecraft came this close.

The Galileo spacecraft travelled over the moon's south pole in 2001, coming to within 181 km (112 miles.) Galileo showed us a lot about the nature of Io's surface.

But Juno is a different spacecraft with more modern instruments and cameras that will fly by Io multiple times. One of the mission's specific goals is to determine if Io has a magma ocean or not. And while the spacecraft's suite of scientific instruments can shed light on that question, Juno also carries a powerful camera that rides shotgun: Junocam.

Junocam was included with the spacecraft primarily to satisfy us, the interested public around the world. It takes high-resolution visible light images that are available for anyone to process and share. Two other imagers were also busy during the Io flyby. One is the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), which takes images in infrared. The other is the Stellar Reference Unit, which usually takes images of stars for navigation.

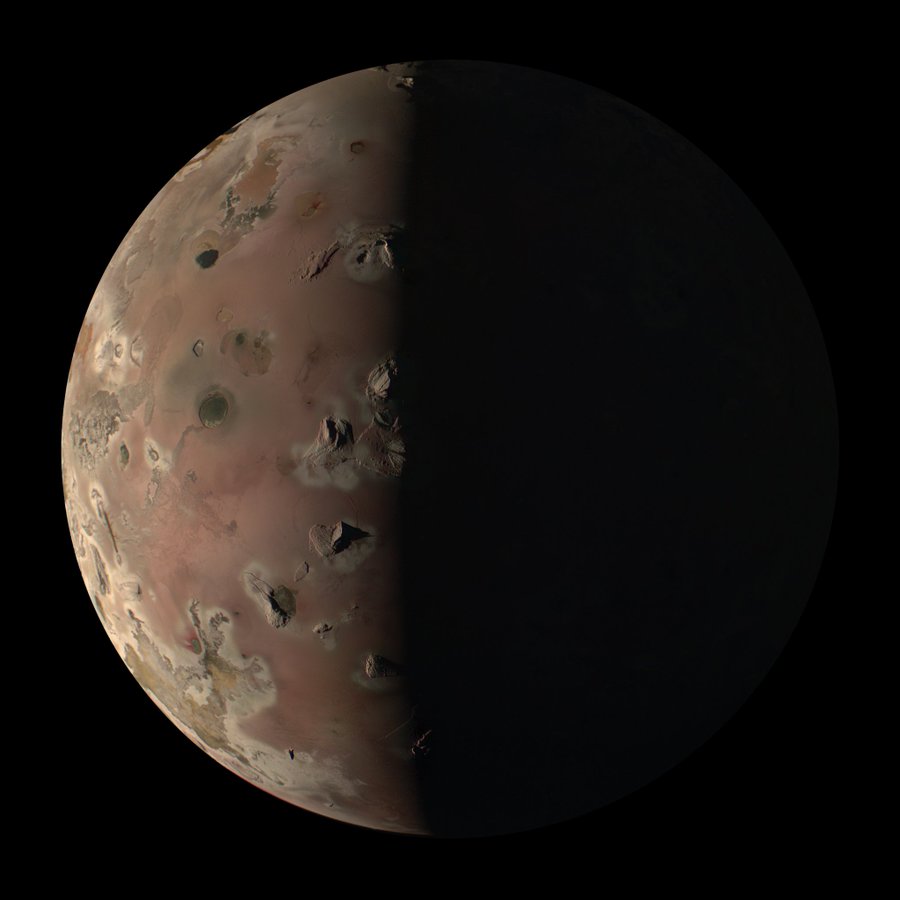

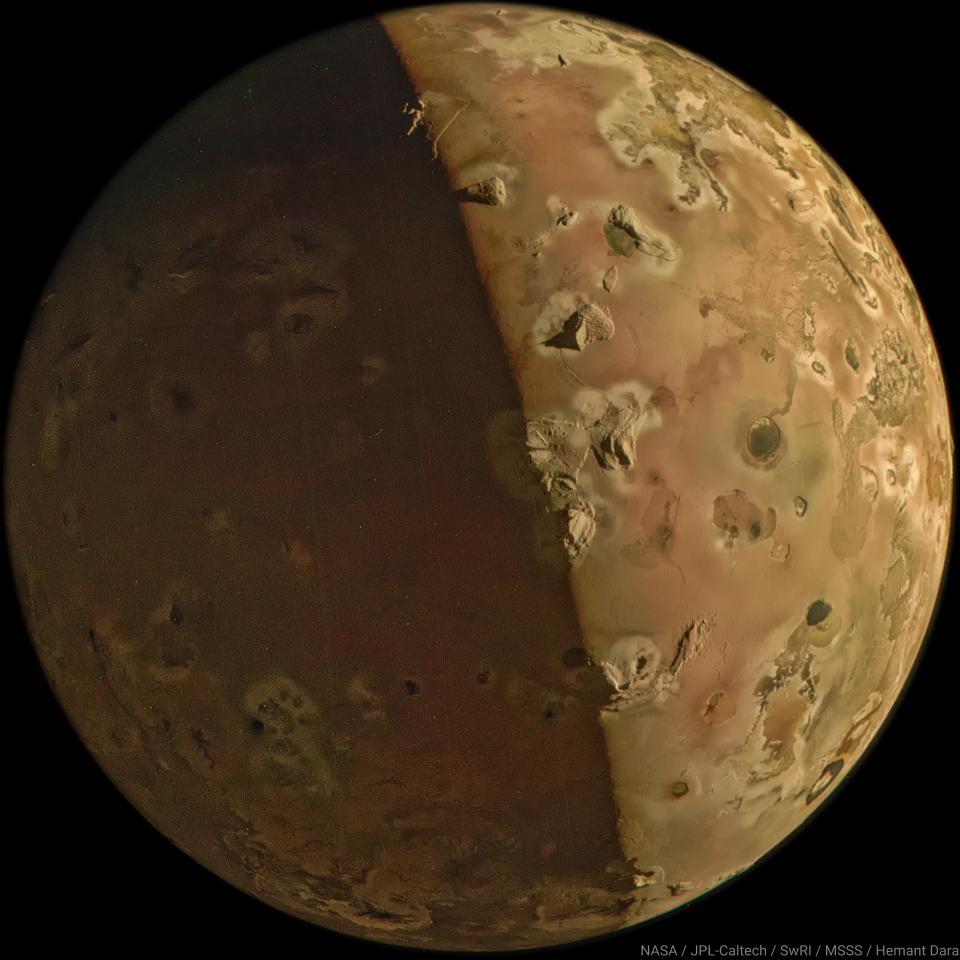

Junocam images get the most attention because NASA makes them available for anyone to process and post. Junocam captured six separate images of the volcanic moon, including black and white and colour. The image below is a composite showing the lit and shadowed sides of Io, processed by Hemant Dara.

Scientists know that Io is the most volcanic body in the Solar System by far. But they hunger for more detailed knowledge of its interior. Juno's series of flybys will allow researchers to watch its volcanoes over time, which will help lead to some new understandings.

"By combining data from this flyby with our previous observations, the Juno science team is studying how Io's volcanoes vary," said Scott Bolton, Juno's principal investigator and a scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, in a statement issued before this most recent flyby. "We are looking for how often they erupt, how bright and hot they are, how the shape of the lava flow changes, and how Io's activity is connected to the flow of charged particles in Jupiter's magnetosphere."

Io remains volcanic to this day because of its eccentric orbit around Jupiter. Jupiter's mass squeezes Io, and the squeezing generates heat that drives its volcanoes. The other Galilean moons add to the effect. The tidal force is so strong that Io's surface can rise and fall by as much as 100 meters.

Io is about the same size as Earth's Moon, yet it's covered in hundreds of active volcanoes. Eruptions can launch lava dozens of kilometres above the moon's surface. There's so much volcanic activity on the surface of Io that some lava flows are hundreds of kilometres long. These voluminous eruptions are like the ones that triggered mass extinctions here on Earth.

Juno's next Io flyby will be on February 3rd. During that visit, Juno will also approach about 1500 km (930 miles) above Io's surface.

"With our pair of close flybys in December and February, Juno will investigate the source of Io's massive volcanic activity, whether a magma ocean exists underneath its crust, and the importance of tidal forces from Jupiter, which are relentlessly squeezing this tortured moon," said Bolton.

Loading tweet...

— View on Twitter

Juno is nearing the end of its mission in 2025. One of the hazards that's bringing its end is Jupiter's intense radiation. The spacecraft's orbits are designed to protect it from Jupiter's radiation, except when it approaches the planet for closer looks. It has to remove itself from the intense radiation to both extend the life of its electronics and allow it to send data back to Earth.

Juno was designed to withstand only 17 orbits of Jupiter but has so far survived 57. With a few more to come, the mission still has lots to teach us about Io and the Jovian system. No doubt we'll be gifted more stunning images and science as it completes its mission.

"Io is only one of the celestial bodies which continue to come under Juno's microscope during this extended mission," said Juno's acting project manager, Matthew Johnson of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. "As well as continuously changing our orbit to allow new perspectives of Jupiter and flying low over the nightside of the planet, the spacecraft will also be threading the needle between some of Jupiter's rings to learn more about their origin and composition."

Io's primary mission ended in July 2021, and its current extended mission will end in September 2025. At that time, the spacecraft will be sent plunging to its destruction in Jupiter's atmosphere, ending its nine-year mission.

But these pictures of Io will always be part of its legacy.

Universe Today

Universe Today