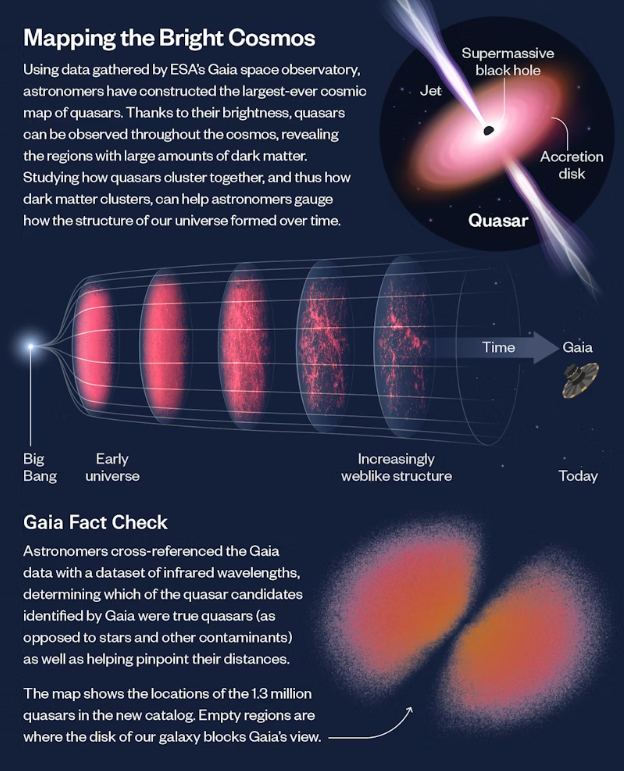

Quasars are the brightest objects in the Universe. The most powerful ones are thousands of times more luminous than entire galaxies. They’re the visible part of a supermassive black hole (SMBH) at the center of a galaxy. The intense light comes from gas drawn toward the black hole, emitting light across several wavelengths as it heats up.

But quasars are more than just bright ancient objects. They have something important to show us about the dark matter.

Large galaxies have supermassive black holes at their centers. Even those only casually familiar with space know that black holes can suck everything in, even light. But as black holes draw nearby gas towards themselves, the gas doesn’t all go into the hole, past the event horizon and into oblivion. Instead, much of the gas forms a rotating accretion disk around the black hole.

SMBHs aren’t always actively drawing material to them, an act known as ‘feeding.’ But when an SMBH is actively feeding, it’s called an active galactic nucleus (AGN.) When the material in the disk rotates, it heats up. As it heats, it emits different wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation. It can also emit jets.

When astronomers first began to detect this light, they only knew they were seeing objects that emitted radio waves. The name quasar means quasi-stellar radio source. But as time went on astronomers learned more, and the term active galactic nucleus was adopted. The term quasar is still used, but they’re now a sub-class of AGN that are the most luminous AGN.

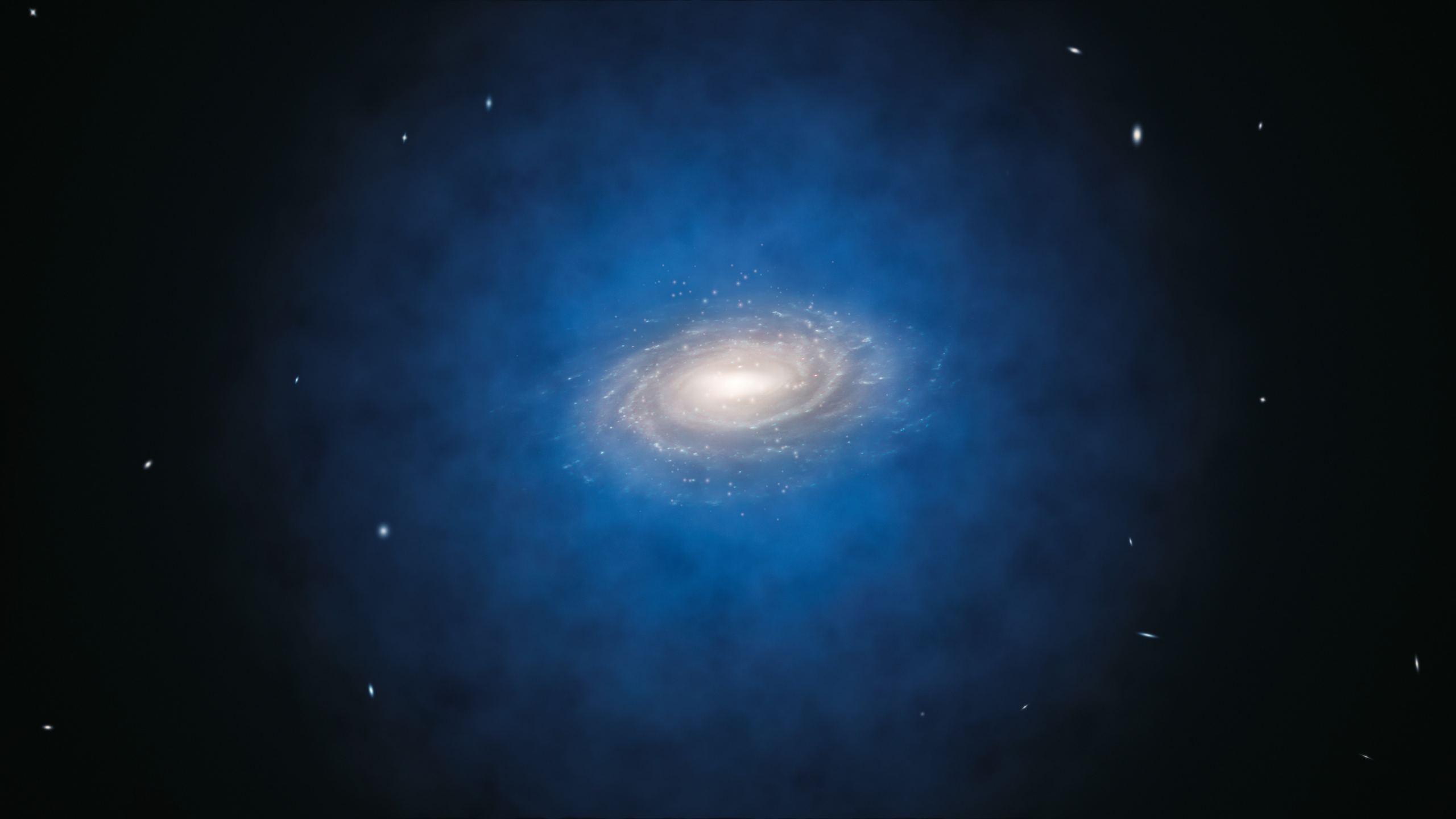

Quasars inhabit galaxies that are surrounded by enormous haloes of dark matter. Astronomers think there’s a link between the dark matter haloes (DMH) and the quasars. The DMH may direct more matter toward the center of the galaxy, feeding the SMBH and igniting a quasar, and even aiding the formation of more massive galaxies.

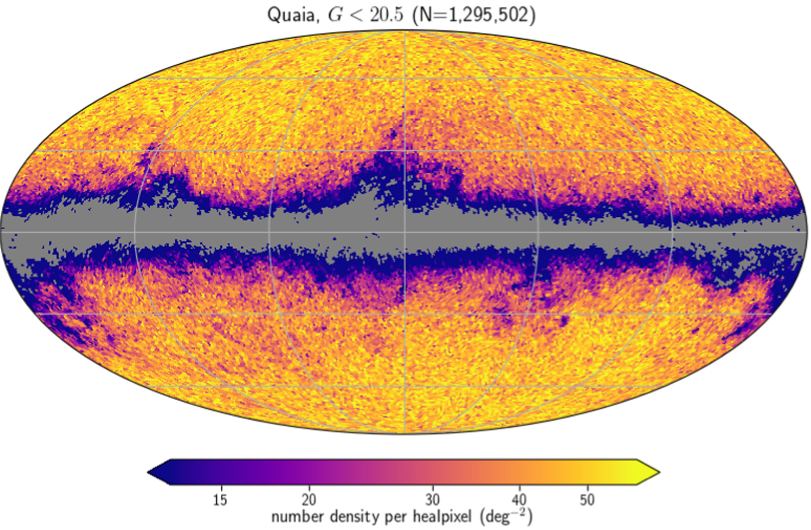

A team of researchers has created a new catalogue of quasars that will be a powerful tool for probing quasars, DMHs, and SMBHs. Their results are in a new paper in The Astrophysical Journal titled “Quaia, the Gaia-unWISE Quasar Catalog: An All-sky Spectroscopic Quasar Sample.” The lead author is Kate Storey-Fisher, a postdoctoral researcher at the Donostia International Physics Center in Spain.

“This quasar catalogue is different from all previous catalogues in that it gives us a three-dimensional map of the largest-ever volume of the universe,” said map co-creator David Hogg, a senior research scientist at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York City and a professor of physics and data science at New York University. “It isn’t the catalogue with the most quasars, and it isn’t the catalogue with the best-quality measurements of quasars, but it is the catalogue with the largest total volume of the universe mapped.”

The fact that the new catalogue captures the largest total volume of the Universe mapped and all the quasars in that space is key to understanding its purpose. It’s not meant as a survey that captures the largest number of quasars. The catalogue is meant to be a tool astrophysicists can use to understand the relationships between quasars, dark matter, black holes, and galaxies.

They call their catalogue Quaia because the data comes from the ESA’s Gaia spacecraft. Gaia’s mission is to map about one billion objects in the Milky Way, mostly stars. And it’s going about its mission with extreme accuracy. But among the multitudes of stars Gaia has mapped is a large number of quasars well beyond the Milky Way. That generated the name “Quaia.”

“We were able to make measurements of how matter clusters together in the early universe that are as precise as some of those from major international survey projects — which is quite remarkable given that we got our data as a ‘bonus’ from the Milky Way–focused Gaia project,” Storey-Fisher says.

Dark matter tends to clump in haloes around galaxies, and studying the distribution of quasars can help explain the distribution of dark matter. In the large scale of the Universe, dark matter is organized as a web, and the catalogue of quasars helps map that web.

The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), a strong piece of evidence for the Big Bang, is also part of this. As the light from the CMB travels toward us through space, the dark matter web’s massive gravitational power bends the light. Scientists can compare the CMB light we receive with the map of quasars and compare the two. The comparisons will them about the relationship between dark matter and quasars and how matter clumps together in the Universe.

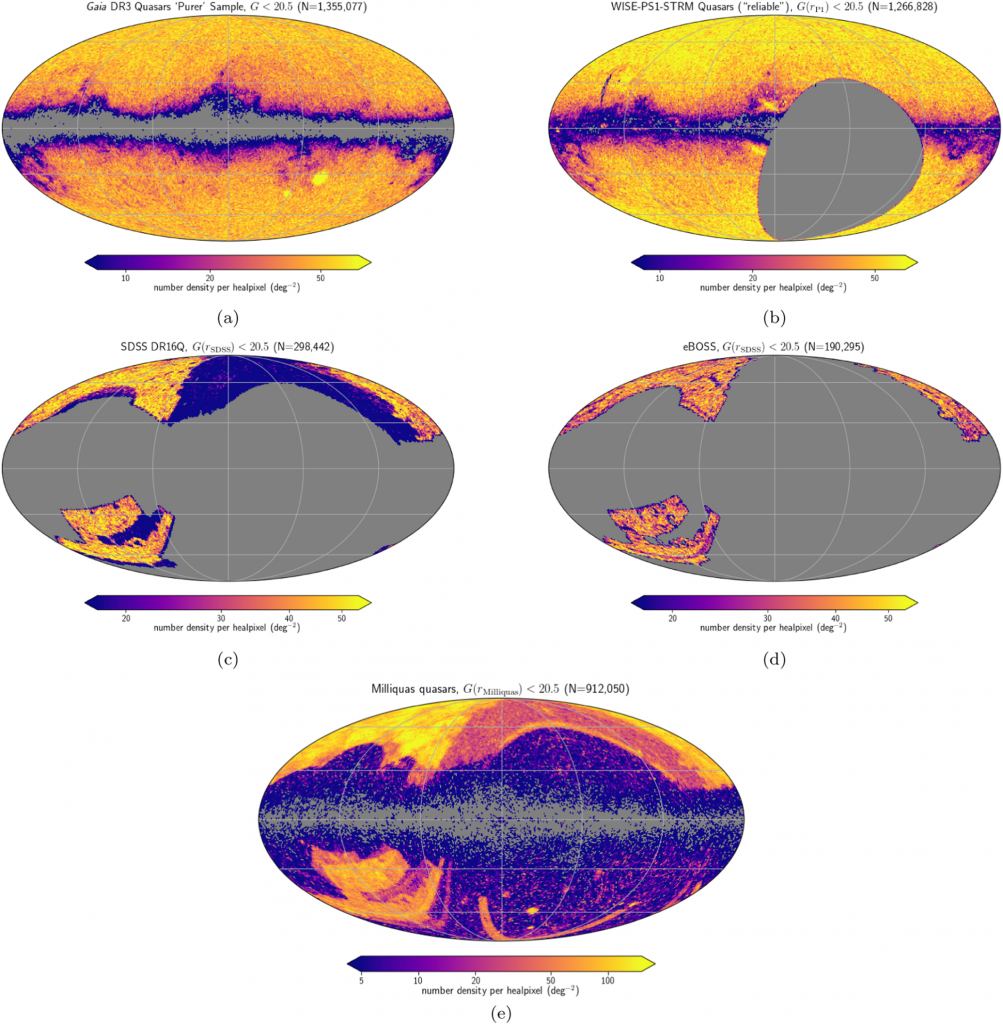

Since quasars trace the cosmic web, their distribution gives information about the web that other sources can’t. For example, it can trace the distribution of matter at higher redshifts than galaxies can. And since it’s space-based, it avoids some of the data contamination that other quasar surveys suffer from, such as the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS.)

This is not the first quasar map/catalogue to be created. There are several others, including one from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

As the animation below shows, Quaia is more complete than the SDSS’s DR16Q, the SDSS’s quasar catalogue that accompanied its data release 16.

Though the Gaia mission itself doesn’t generate many of its own headlines, it’s at the foundation of modern space science. Its data is behind lots of published research.

“This quasar catalogue is a great example of how productive astronomical projects are,” says Hogg. “Gaia was designed to measure stars in our own galaxy, but it also found millions of quasars at the same time, which give us a map of the entire universe.”

Now, the new Quaia catalogue is playing a similar role. The data it contains is already being used by other researchers.

“It has been very exciting to see this catalogue spurring so much new science,” Storey-Fisher says. “Researchers around the world are using the quasar map to measure everything from the initial density fluctuations that seeded the cosmic web to the distribution of cosmic voids to the motion of our solar system through the universe.”