Like a pilgrim seeking wisdom, NASA's MSL Curiosity has been working its way up Mt. Sharp, the dominant central feature in Gale Crater. Now, almost 12 years into its mission, the capable rover has reached an interesting feature that could tell them more about Mars and its watery history. It's called the Gediz Vallis channel.

Gediz Vallis channel appears to have been carved by ancient water. But if that's the case, it happened billions of years ago. The channel has since filled with rock.

Mt. Sharp's upper regions are beyond Curiosity's reach. It's simply too difficult for the rover to get there. But Nature is playing nice with MSL Curiosity. Rocks have come tumbling down from the mountain, creating a ridge and filling up a channel. Those rocks are within reach, and they could hold clues to Mars' watery past.

Mars' ancient history, especially as it concerns surface liquid water, is a gigantic puzzle with lots of pieces. We know there are hydrated minerals on Mars that date back millions of years. We know there are sulphates, which are minerals left behind when water evaporates. We have orbiter images clearly showing river channels and deltas.

Gediz Vallis is a tiny part of Mars, but it could make an important contribution to our understanding of this once warm and wet world.

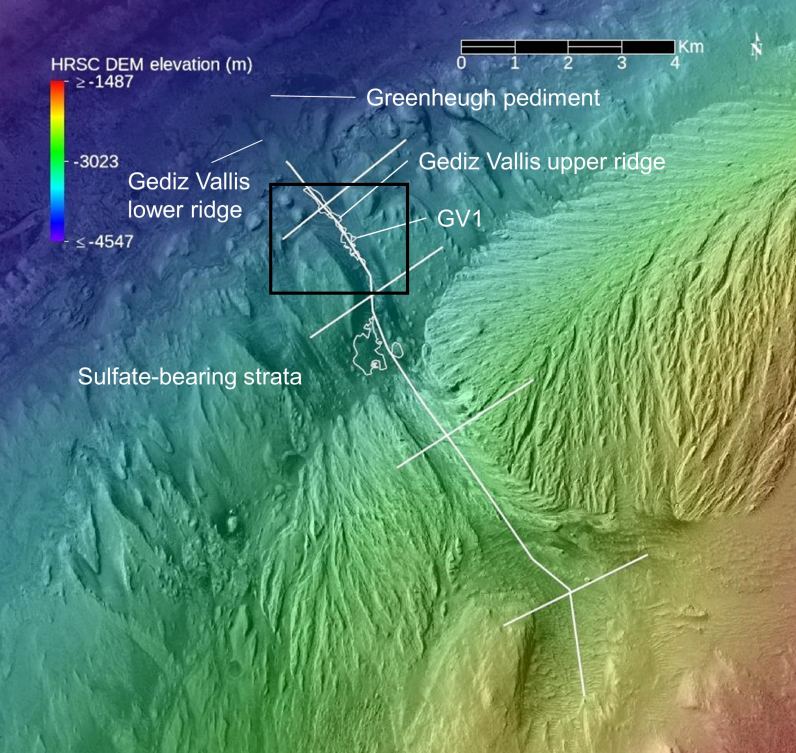

Understanding Gediz Vallis and what it could tell us begins with Mt. Sharp. Mt. Sharp was built up over long periods of geological time by the deposit of sediments into layers. Over time, some of this material was eroded away, presenting us with what we see today. The Gediz Vallis channel formed after all that had happened.

Because the channel has steep walls, scientists say water had to carve it. Wind erosion is ruled out because it creates shallow, wide walls. Sometime after it formed, it was filled with rocky debris. That debris probably came from high up Mt. Sharp, beyond Curiosity's reach. The rock will give the rover a look at the upper reaches of the mountain that it would otherwise never obtain.

Ashwin Vasavada is the Project scientist for NASA's Curiosity rover at JPL. "If the channel or the debris pile were formed by liquid water, that's really interesting," he said in a press release. "It would mean that fairly late in the story of Mount Sharp – after a long dry period – water came back, and in a big way."

This agrees with other evidence Curiosity found. Instead of disappearing once and for all, water seems to have come and gone in phases, confounding our attempts to understand Mars' history.

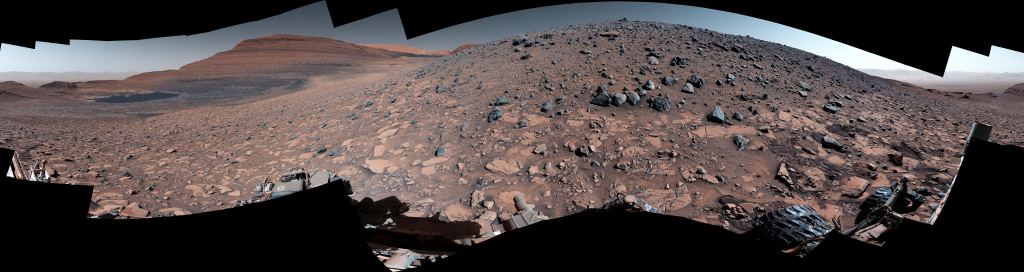

A year ago, the rover ascended the Gediz Vallis ridge, a sprawling debris pile that appears to grow out of the end of the channel, to get a closer look. Since the debris looks like it flows out of the channel, it indicates that both are results of the same geological process.

Even though MSL Curiosity is an engineering marvel, the rover will still need months to study the Gediz Vallis Channel. What it uncovers over the following months could give scientists a lot more detail about the history of Mars' water.

Recently published research based partly on Curiosity's data also shows that Mars had episodes of water and that it didn't all disappear at once. That research showed that the bulk of Mt. Sharp was formed by waterborne sediments and that after that happened, another layer made of windborne sediments formed on top of it. But images of the windborne layer show that the sedimentary rock is deformed by the later presence of water.

How Gediz Vallis fits into Mars' story is unclear. But getting a closer look will start to untangle the planet's complex history. Was the channel carved by water? If Curiosity can confirm that, then it's more evidence that Mars had surface water more recently than though. Did water carry the boulders and debris that filled it, or did dry avalanches?

Curiosity needs months to explore the region. Once researchers have had time to digest and interpret the rover's data, we'll get more answers.

Universe Today

Universe Today