Earth is the only life-supporting planet we know of, so it's tempting to use it as a standard in the search for life elsewhere. But the modern Earth can't serve as a basis for evaluating exoplanets and their potential to support life. Earth's atmosphere has changed radically over its 4.5 billion years.

A better way is to determine what biomarkers were present in Earth's atmosphere at different stages in its evolution and judge other planets on that basis.

That's what a group of researchers from the UK and the USA did. Their research is titled " The early Earth as an analogue for exoplanetary biogeochemistry," and it appears in Reviews in Mineralogy. The lead author is Dr. Eva E. Stüeken, a professor in the School of Earth & Environmental Sciences, University of St Andrews, UK.

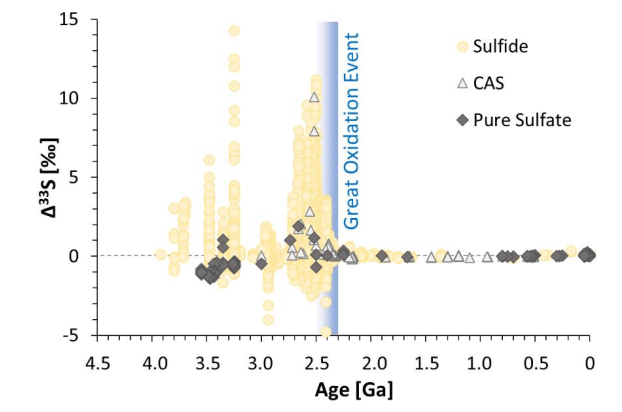

When Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago, its atmosphere was nothing like it is today. At that time, the atmosphere and oceans were anoxic. About 2.4 billion years ago, free oxygen began to accumulate in the atmosphere during the Great Oxygenation Event, one of the defining periods in Earth's history. But the oxygen came from life itself, meaning life was present when the Earth's atmosphere was much different.

This isn't the only example of how Earth's atmosphere has changed over geological time. But it's an instructive one and shows why searching for life means more than just searching for an atmosphere like modern Earth's. If that's the way we conducted the search, we'd miss worlds where photosynthesis hadn't yet appeared.

In their research, the authors point out how Earth hosted a rich and evolving population of microbes under different atmospheric conditions for billions of years.

"For most of this time, Earth has been inhabited by a purely microbial biosphere albeit with seemingly increasing complexity over time," the authors write. "A rich record of this geobiological evolution over most of Earth's history thus provides insights into the remote detectability of microbial life under a variety of planetary conditions."

It's not just life that's changed over time. Plate tectonics have changed and may have been 'stagnant lid' tectonics for a long time. In stagnant lid tectonics, plates don't move horizontally. That can have consequences for atmospheric chemistry.

The main point is that Earth's atmosphere does not reflect the solar nebula the planet formed in. Multiple intertwined processes have changed the atmosphere over time. The search for life involves not only a better understanding of these processes, but how to identify what stage exoplanets might be in.

It's axiomatic that biological processes can have a dramatic effect on planetary atmospheres. "On the modern Earth, the atmospheric composition is very strongly controlled by life," the researchers write. "However, any potential atmospheric biosignature must be disentangled from a backdrop of abiotic (geological and astrophysical) processes that also contribute to planetary atmospheres and would be dominating on lifeless worlds and on planets with a very small biosphere."

The authors outline what they say are the most important lessons that the early Earth can teach us about the search for life.

The first is that the Earth has actually had three different atmospheres throughout its long history. The first one came from the solar nebula and was lost soon after the planet formed. That's the primary atmosphere. The second one formed from outgassing from the planet's interior. The third one, Earth's modern atmosphere, is complex. It's a balancing act involving life, plate tectonics, volcanism, and even atmospheric escape. A better understanding of how Earth's atmosphere has changed over time gives researchers a better understanding of what they see in exoplanet atmospheres.

The second is that the further we look back in time, the more the rock record of Earth's early life is altered or destroyed. Our best evidence suggests life was present by 3.5 billion years ago, maybe even by 3.7 billion years ago. If that's the case, the first life may have existed on a world covered in oceans, with no continental land masses and only volcanic islands. If there had been abundant volcanic and geological activity between 3.5 and 3.7 billion years ago, there would've been large fluxes of CO2 and H2. Since these are substrates for methanogenesis, then methane may have been abundant in the atmosphere and detectable.

The third lesson the authors outline is that a planet can host oxygen-producing life for a long time before oxygen can be detected in an atmosphere. Scientists think that oxygenic photosynthesis appeared on Earth in the mid-Archean eon. The Archean spanned from 4 billion to 2.5 billion years ago, so mid-Archean is sometime around 3.25 billion years ago. But oxygen couldn't accumulate in the atmosphere until the Great Oxygenation Event about 2.4 billion years ago. Oxygen is a powerful biomarker, and if we find it in an exoplanet's atmosphere, it would be cause for excitement. But life on Earth was around for a long time before atmospheric oxygen would've been detectable.

The fourth lesson involves the appearance of horizontal plate tectonics and its effect on chemistry. "From the GOE onwards, the Earth looked tectonically similar to today," the authors write. The oceans were likely stratified into an anoxic layer and an oxygenated surface layer. However, hydrothermal activity constantly introduced ferrous iron into the oceans. That increased the sulphate levels in the seawater which reduced the methane in the atmosphere. Without that methane, Earth's biosphere would've been much less detectable. Complicated, huh?

"Planet Earth has evolved over the past 4.5 billion years from an entirely anoxic planet

with possibly a different tectonic regime to the oxygenated world with horizontal plate

tectonics that we know today," the authors explain. All that complex evolution allowed life to appear and to thrive, but it also made detecting earlier biospheres on exoplanets more complicated.

We're at a huge disadvantage in the search for life on exoplanets. We can literally dig into Earth's ancient rock to try to untangle the long history of life on Earth and how the atmosphere evolved over billions of years. When it comes to exoplanets, all we have is telescopes. Increasingly powerful telescopes, but telescopes nonetheless. While we are beginning to explore our own Solar System, especially Mars and the tantalizing ocean moons orbiting the gas giants, other solar systems are beyond our physical reach.

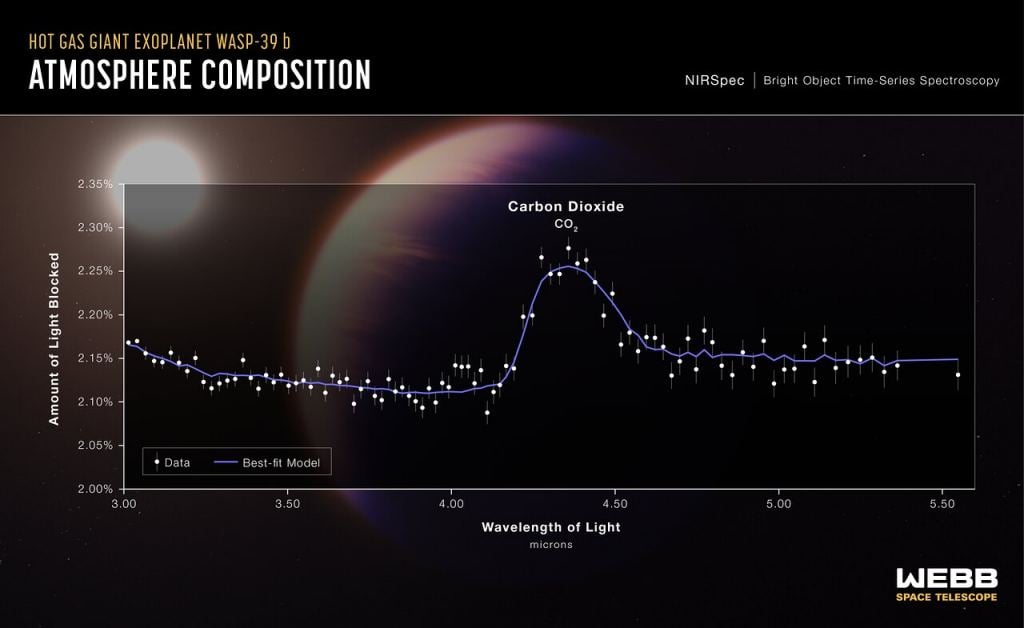

"We must instead remotely recognize the presence of alien biospheres and characterize their biogeochemical cycles in planetary spectra obtained with large ground- and space-based telescopes," the authors write. "These telescopes can probe atmospheric composition by detecting absorption features associated with specific gases." Probing atmospheric gases is our most powerful approach right now, as the JWST shows.

But as scientists get better tools, they'll start to go beyond atmospheric chemistry. "We might also be able to recognize global-scale surface features, including light interaction with photosynthetic pigments and 'glint' arising from specular reflection of light by a liquid ocean."

Understanding what we're seeing in exoplanet atmospheres parallels our understanding of Earth's long history. Earth could be the key to our broadening and accelerating search for life.

"Unravelling the details of Earth's complex biogeochemical history and its relationship with remotely observable spectral signals is an important consideration for instrument design and our own search for life in the Universe," the authors write.

Universe Today

Universe Today