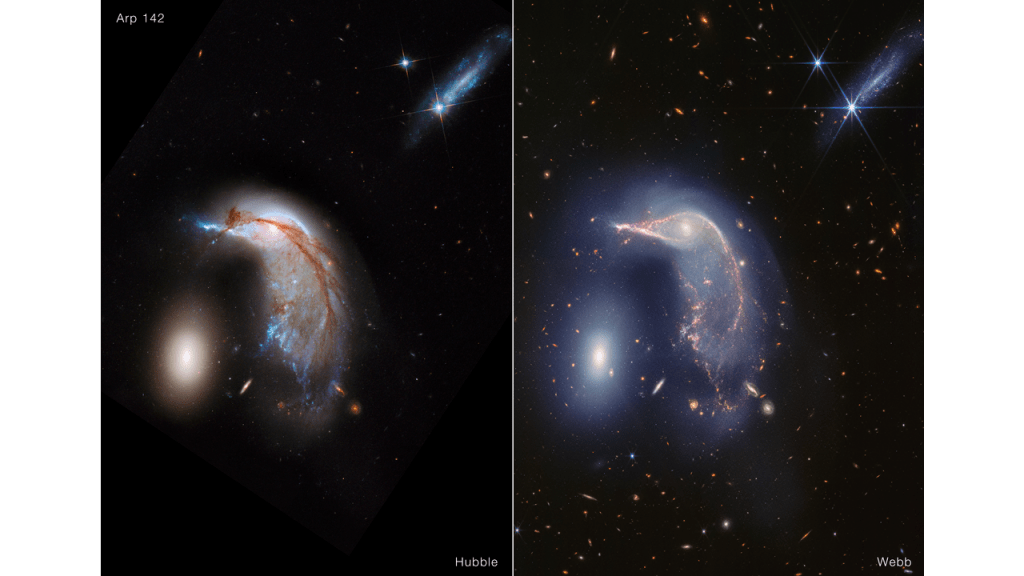

What happens when a spiral and an elliptical galaxy collide? To celebrate the second anniversary of the "first light" for the Webb telescope, NASA released an amazing infrared view of two galaxies locked in a tight dance. They're called the Penguin and the Egg and their dance will last hundreds of millions of years.

"In just two years, Webb has transformed our view of the universe, enabling the kind of world-class science that drove NASA to make this mission a reality," said Mark Clampin, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. "Webb is providing insights into longstanding mysteries about the early Universe."

Webb Witnesses a Galactic Dance

The telescope targeted a collision scene named Arp 142 containing both galaxies—a scene that the Hubble Space Telescope has also explored. They lie about 326 million light-years away. Their first close encounter began somewhere between 25 and 75 million years ago. That's when two partner galaxies had the first of many passages that will distort their shapes more than they already appear here.

Webb's observations, which combine near- and mid-infrared light from Webb's NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), respectively, clearly show that a hazy cloud of gas and stars (blue) links them together. The close approach also set off tremendous bursts of star birth in the colliding clouds of gas and dust.

Eventually, after several close approaches in their cosmic dance, these two galaxies will merge completely. Observers hundreds of millions of years in the future will look at Arp 142 and see one massive elliptical galaxy.

Interestingly, Webb's sharp infrared eyes also picked out very distant galaxies. Some lie beyond this cosmic collision, although at least one lies about a hundred million light-years closer to Earth. It bristles with hot, young, newborn stars.

How The Arp 142 Galaxies Experience a Merger

The Penguin and Egg galaxies lie about 100,000 light-years apart but they affect each other. The Egg's gravitational pull distorts the spiral and that interaction is "sculpting" the Penguin. The core makes up the eye of a penguin. The slowly unwinding spiral arms form a beak, head, backbone, and tail.

Webb's infrared view reveals otherwise unseen activity between the two. For example, the Penguin is rich in dust. Webb's view shows us how gravitational interactions pull that dust away from the Penguin. There are also scads of new stars in the galaxy, surrounded by what looks like smoke. Webb's view shows this hydrogen cloud. It's rich in carbon-based molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These are incredibly abundant in the Universe and astronomers find them just about everywhere they point a telescope.

By contrast, in Webb's view, the Egg looks like it's hardly been touched—it's still an egg-shaped elliptical. It has much older stars than the Penguin. Past epochs of star birth have pretty much used up the available star-making material. So, even though the two galaxies have about the same mass, the Egg just doesn't have as much material to get stretched out or turned into stars.

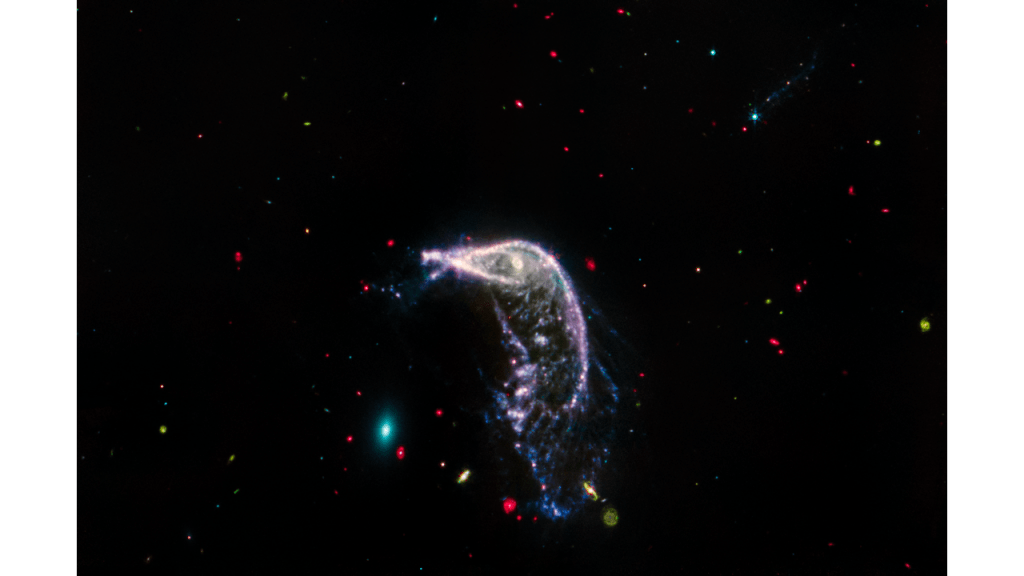

Zeroing in on Webb's Two Views

If you look at both of Webb's infrared views of the galaxy collision, you can see marked differences in them. That's because each one prioritizes a different set of infrared wavelengths. In the mid-infrared view, the egg looks tiny and washed out. That's because the instrument sees only the old stars in the Egg. By contrast, the Penguin's distorted core and spiral arms are brimming with young stars embedded in the PAH-rich hydrogen clouds.

The combined near- and mid-infrared view shows more of the gas clouds as the Egg tears them away from the Penguin. These regions will glitter in the future with the light of newly formed stars. For now, however, only cooler, older stars are visible in the combined image. The younger ones are there, but the mid-infrared-sensitive instrument doesn't spot them.

Here's a flythrough visualization of Arp 142. NASA, ESA, CSA, Ralf Crawford (STScI), Joseph DePasquale (STScI), Christian Nieves (STScI), Joseph Olmsted (STScI), Alyssa Pagan (STScI), Frank Summers (STScI), Greg Bacon (STScI)Why Does Webb Study Galaxy Collisions?

By studying this galactic collision site, the Webb telescope further probes the activity as galaxies evolve. Collisions are an integral part of this process. Our Milky Way Galaxy will dance with the nearby Andromeda Galaxy, starting in about 5 billion years. Images and data from observations of other galaxies doing the same thing give astronomers a chance to understand the process and forecast the distant future when something called "Milkdromeda" will contain the stars and planets of two spirals that once were close neighbors.

For More Information

Vivid Portrait of Interacting Galaxies Marks Webb's Second Anniversary

Galaxy Evolution

Universe Today

Universe Today