Astronauts sometimes struggle to consume enough nutritious food on the ISS because it tastes bland. But astronaut food is of high quality and designed to be palatable and to meet nutrition needs. What's the problem?

NASA has two facilities devoted to astronaut food: the Space Food Systems Laboratory at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Space Food Research Facility, also in Texas. Both facilities support the production and development of astronaut food— including menus, packaging, and hardware—for all of NASA's space programs. There's even an Advanced Food Research Team looking ahead to future space missions that will travel beyond the ISS and Low-Earth Orbit (LEO).

Astronauts have a variety of foods available to them. Foods range from freeze-dried or dehydrated foods like scrambled eggs and mashed potatoes to "canned" type foods like ravioli and meatloaf to irradiated foods like smoked turkey. They even have unprepared foods like nuts and granola bars.

But despite these dedicated efforts to provide a variety of quality foods with enjoyable tastes, astronauts regularly report that their food tastes bland in space.

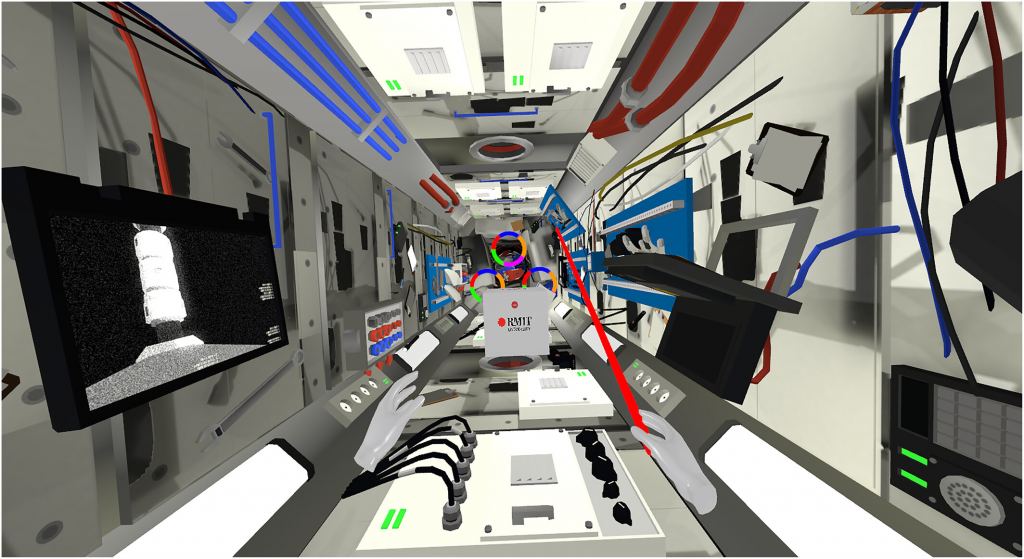

Researchers at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) University are using Virtual Reality to research the cause of this problem. They've published a study in the International Journal of Food Science and Technology that presents their results. Its title is " Smell Perception in Virtual Spacecraft? A Ground-Based Approach to Sensory Data Collection. " The lead researcher is Julia Low from the School of Science at RMIT.

"The incredible thing with this VR study is that it really does go a very long way to simulating the experience of being on the space station."Gail Iles, study co-author, RMIT

Scientists—and the rest of us—know that the senses of smell and taste are linked. They're both based on chemistry. Taste buds on our tongues sense the five basic flavours: umami, sweet, salty, sour, and bitter. The olfactory sensors in our noses sense thousands of odours. Our brains combine all of these signals, and people who've lost their sense of smell report that food tastes bland.

Have astronauts lost their sense of smell? Are their senses of smell and taste altered somehow aboard the ISS?

"Contextual factors shape the overall food consumption experience," the authors write in their paper. "Extreme consumption contexts like outer space present logistical, ethical and financial challenges for food sensory evaluation. Yet, these evaluations are necessary as the sensory aspects of palatability and variety enhance psychological and behavioural outcomes in space," they write. Behavioural outcomes are particularly important in space for obvious reasons, and NASA and other space agencies are keenly interested in positive outcomes.

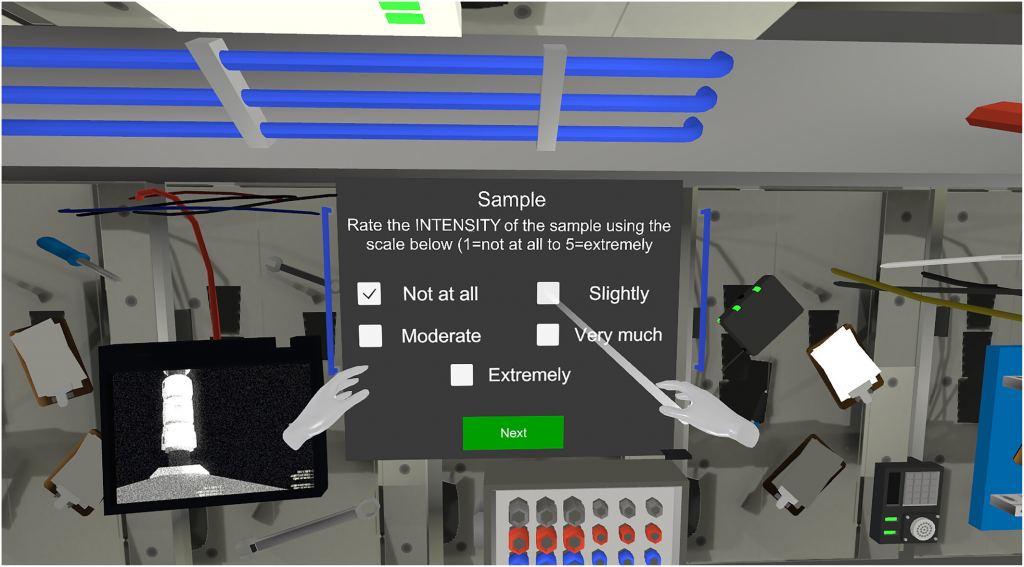

In this study, the researchers looked at three powerful food aromas: almond extract, vanilla extract, and lemon essential oils. They tested how 54 adults perceived these distinct aromas under normal Earth conditions and under VR-simulated International Space Station conditions.

The results showed that two of the aromas, vanilla and almond, were perceived more intensely in the simulated ISS environment. The lemon scent was unchanged. The researchers found a sweet chemical in common in vanilla and almond called benzaldehyde. They think this chemical could be involved in the change in perceptions, alongside an individual's sensitivity to the particular aroma.

Interestingly, a person's mindset and emotions also play a role in their perception of the aromas.

"A greater sense of loneliness and isolation may also play a role, and there are implications from this study around how isolated people smell and taste food," Low said.

Scientists have examined these issues before, not only in space but in confined, isolated Antarctic research stations. They've found that people in these environments can experience a significant change in their sense of smell. "These findings may hint at the potential impact of such environments on olfactory function," they write.

The low-gravity environment also affects astronauts. "Space travellers have noted a shift in taste perception, indicating that food is less flavourful/tasteful in space," the authors write. "This change is initially linked to microgravity-induced fluid shifts, potentially affecting olfactory abilities."

On Earth, the planet's powerful gravity draws body fluids downward. In a microgravity environment in space, more fluids can collect in the head. When fluids collect in the nasal passages, it can hinder an astronaut's senses of smell and taste. When combined with the stress of isolation and confinement, and with the conditions inside the spacecraft, like humidity and the presence of airborne compounds, the result can be bland food.

These fluid effects dissipate after a few weeks on board the ISS. Yet astronauts still report not enjoying their food. "Astronauts are still not enjoying their food even after fluid shift effects have gone, suggesting that there's something more to this," Low said.

"One of the long-term aims of the research is to make better-tailored foods for astronauts, as well as other people who are in isolated environments, to increase their nutritional intake closer to 100%," lead researcher Julia Low said. This could extend to elders in nursing homes and could lead to more personalized food aromas to make nutritious food more palatable. (And if you're of a dystopian frame of mind, could be used to make Soylent Green more tasty.)

"What we're going to see in the future with the Artemis missions are much longer missions, years in length, particularly when we go to Mars, so we really need to understand the problems with diet and food and how crew interact with their food," said Gail Iles. Iles is one of the study's co-authors, an Associate Professor at RMIT, and a former astronaut trainer. "The incredible thing with this VR study is that it really does go a very long way to simulating the experience of being on the space station. And it really does change how you smell things and how you taste things."

Food chemistry expert and Associate Professor Jayani Chandrapala is another of the study's co-authors. Chandrapala emphasized the role that benzaldehyde, the common chemical compound in vanilla and almond, played in the results.

"In our study, we believe that it's this sweet aroma that gives that highly intensive aroma within the VR setting," said Chandrapala from the School of Science.

By combining taste and aroma perception, emotional settings, and VR, this study tackles one of the seldom-discussed aspects of future space travel beyond LEO. Discussions about long-term missions to Mars often focus on protecting astronauts from hazards like radiation, loss of bone density, and muscle atrophy. But nutrition is also foundational to mission success. A successful journey to Mars and back depends on getting as many details right as possible.

But these results extend to people in isolated settings here on Earth, too.

"The results of this study could help personalize people's diets in socially isolated situations, including in nursing homes, and improve their nutritional intake," Low said.

"These findings present opportunities for innovation in ground-based space sensory research and personalized eating experiences, refining immersive tools for future studies," the authors write in their conclusion. "Such methods may expand beyond space applications, benefitting populations experiencing isolation and/or confined conditions, such as the elderly living alone, military personnel and individuals with limited mobility."

Universe Today

Universe Today