Check any container of over-the-counter medicine, and you’ll see its expiration date. Prescription medicines have similar lifetimes, and we’re told to discard old medications rather than hold on to them. Most of them lose their effectiveness over time, and some can even become toxic. We’re discouraged from disposing of them in our wastewater because they can find their way into other organisms, sometimes with deleterious effects.

We can replace them relatively easily on Earth, but not on a space mission beyond Low Earth Orbit.

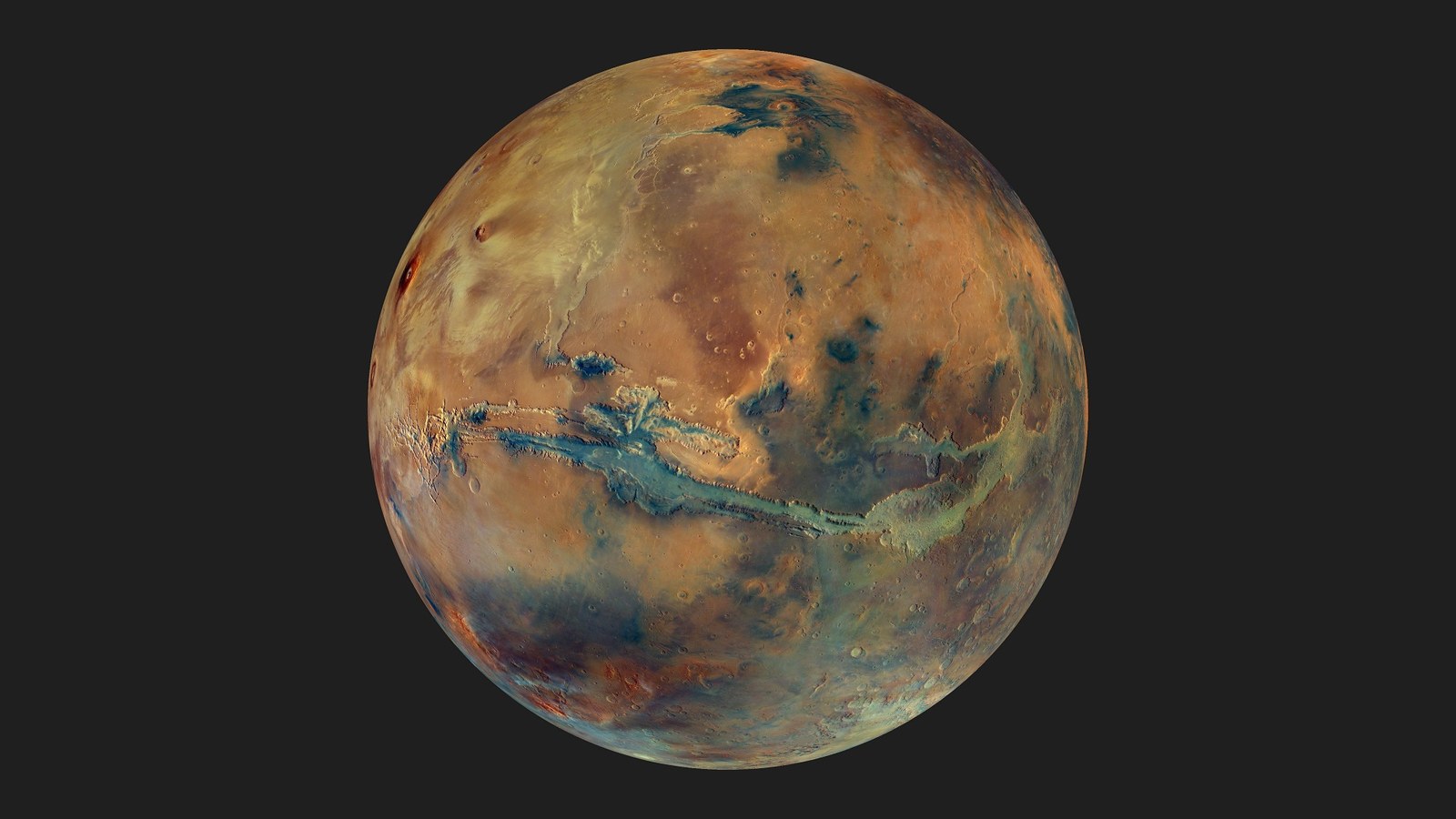

A round trip to Mars takes about three years. A lot can happen in that time. Important medical supplies, including medicines, might not remain as effective for that long.

That could create problems for astronauts who make the journey.

New research in Nature’s npj Microgravity examines the lifetimes of medicines and how they could affect astronauts on long-duration space missions. It’s titled “Expiration analysis of the International Space Station formulary for exploration mission planning,” and the senior author is Daniel Buckland. Buckland is from the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Duke University School of Medicine and is an aerospace medicine researcher. The lead author is Thomas Diaz, a pharmacy resident at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Getting sick in space isn’t rare. Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield talked about the problem in 2013. “When we first get to space, we feel sick. Your body is really confused. And so, you know, you’re dizzy, your lunch is floating around in your belly ’cause you’re floating, and what you see doesn’t match what you feel.” NASA calls it ‘space adaptation syndrome,’ and motion sickness and anti-nausea medications can help.

Research also shows that astronauts’ immune systems are weakened in space. Weaker immune systems raise the risk of infections. Humans carry latent viruses that can become active when immune systems are weakened, and the entire problem is amplified on longer missions.

When used properly and early enough, common medications can prevent relatively simple afflictions, such as a minor infection, from growing into more dangerous problems. Expired medications can create a problem because their effectiveness is often diminished over time.

“Effective medications will be required to maintain human health for long-duration space operations,” the authors write in their paper. “Previous studies have explored the stability and potency of several of the medications used on the International Space Station (ISS).”

However, this is the first time researchers have compared medications used in space with drug expiration dates in four different international drug registries.

Lead author Thomas Diaz got the idea for this work and then contacted Buckland.

“Tom reached out with the idea, knowing my work on risk mitigation for extended spaceflight,” said Buckland. “He was concerned that not enough research addressed the problem of medication longevity on a Mars mission.”

NASA doesn’t reveal what medicines it stores on the ISS. For this research, Diaz used a Freedom of Information Act Request to get the list of medicines. The researchers assumed that the formulary would be the same or at least similar for a Mars mission.

The ISS carries 111 medications, divided among five different colour-coded kits. Each kit holds medicines pertinent to its designated use.

- Convenience kit: 23 medications.

- Emergency/Advance Life Support: 4 medications.

- Oral Medication: 36 medications.

- Topical and Injectable: 37 medications.

- Vascular Contingency: 11 medications.

Some medications are duplicated in multiple kits, and two of them are diluents for other medications.

The ISS’s formulary, a list of drugs stocked on the station, contains 106 medications, excluding multiples and diluents. The most common issues that need to be addressed with medicines are motion sickness, allergies, minor pains, and infections. The list of medicines includes antibiotics, sleep aids, pain relievers, and allergy medicines. The drugs are chosen because they are effective in microgravity environments and because they have longer shelf lives than similar medications.

The research shows that over half of the medicines stocked on the ISS would expire on a Mars mission before astronauts returned to Earth.

“Of the 106 medications in the ISS formulary, shelf-life data was found in at least 1 of the registries for 91 (86%) medications,” the authors write in their research. “Of these 91 medications, 54 have an estimated terrestrial shelf-life of less than or equal to 36 months when stored in their original packaging. 14 will expire in less than 24 months.”

“It doesn’t necessarily mean the medicines won’t work, but in the same way you shouldn’t take expired medications you have lying around at home, space exploration agencies will need to plan on expired medications being less effective,” said Buckland.

On Earth, different medications become less effective at different rates after expiration. However, the effects of space flight on their effectiveness are largely unknown. Space is a harsh environment, and radiation could have a pronounced effect on medications. Increasing the amount of each medication carried on a Mars mission could help deal with the problem, but it’s a rather clumsy solution.

“Hopefully, this work can guide the selection of appropriate medications or inform strategies to mitigate the risks associated with expired medications on long-duration missions,” Buckland said.??

“Prior experience and research show astronauts do get ill on the ISS, but there is real-time communication with the ground and a well-stocked pharmacy that is regularly resupplied, which prevents small injuries or minor illnesses from turning into issues that affect the mission,” he said.??

In their conclusion, the researchers note that pharmaceutical drugs will be the cornerstone of astronaut health on long missions. They also point out a gap in data regarding the shelf lives of the drugs in the ISS’s formulary. For example, 14% of the medicines in the formulary lack expiration data. “It is imperative to know and understand these pharmacologic parameters in order to supply a safe and effective astropharmacy,” they write.

If medicines become unstable sooner on long space missions, it’s a problem that needs to be addressed.

“Ultimately, those responsible for the health of spaceflight crews will have to find ways to extend the expiration of medications to the complete mission duration or accept the elevated risk associated with administration of an expired medication,” they conclude.