Ages ago in its youth, Mars appeared much like Earth. It was a warm planet with lakes, rivers, and vast seas. It had a thick atmosphere with clouds and rain. One major difference is that the atmosphere was rich with carbon dioxide instead of oxygen. Then about 3.5 billion years ago much of the atmosphere disappeared, and we haven't understood how. A new study in *Science Advances* suggests that the waters of Mars may have been the key, and much of the ancient atmosphere may be locked in the surface of the red planet.

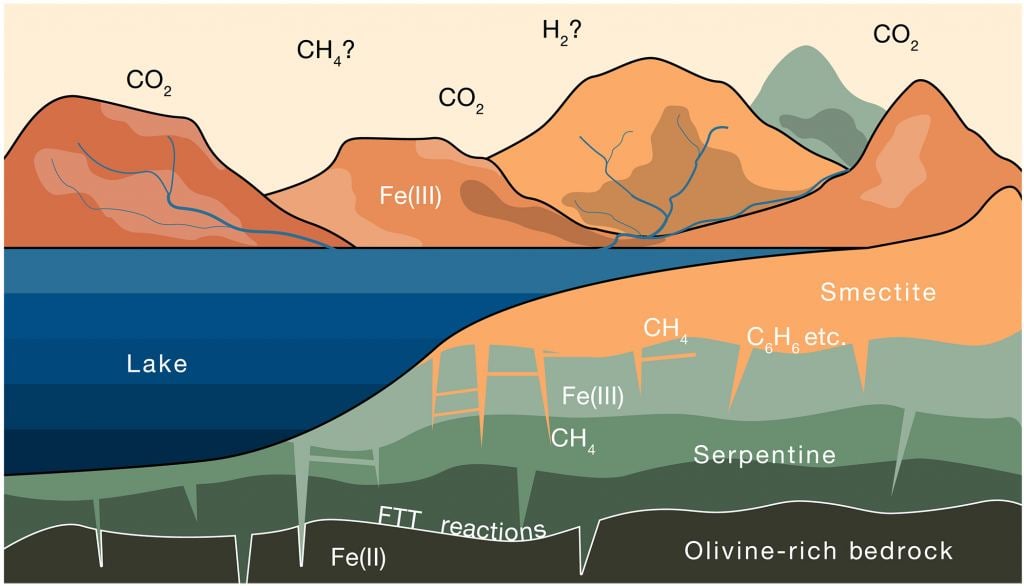

The authors center their paper on a clay mineral known as smectite. On Earth smectite is produced through tectonic activity. As tectonic plates are uplifted they can drag material from the mantle to the surface, some of which is this kind of clay. One characteristic of smectite is that it's full of little folds. Nooks and crannies if you will, that can trap carbon dioxide for billions of years. In an earlier study the team demonstrated how smectite on Earth helped prevent our world from becoming a greenhouse planet by pulling carbon dioxide out of our early atmosphere. It's a process still going on today. Mars doesn't experience tectonic activity, but smectite can be found all over Mars, and the authors wondered if it might solve the mystery of the Martian atmosphere.

The challenge was to figure out how so much smectite formed on Mars. Rather than uplifting tectonic plates it is a series of chemical reactions. The authors suggest that water on Mars seeped through olivine, a magnesium iron silicate common on Earth, Mars, and even asteroids. The iron in olivine would bind with the water's oxygen and release hydrogen. This hydrogen would then react with carbon dioxide to form methane. Over time this process would transform the olivine into smectite, which would trap methane and carbon dioxide. Based on their calculations the team argues that 80% of the ancient atmosphere is now trapped in the Martian clay, leaving the thin atmosphere we see today.

If this model is true, it could be a boon for future Martian explorers. Not only will there be plenty of water found beneath the surface, there will also be large quantities of methane. The solution to the problems of water and fuel could be right under the feet of those first explorers, trapped in the nooks and crannies of common clay.

Reference: Murray, Joshua & Jagoutz, Oliver. " Olivine alteration and the loss of Mars’ early atmospheric carbon." *Science Advances* 10.39 (2024): eadm8443.

Reference: Murray, Joshua, and Oliver Jagoutz. " Palaeozoic cooling modulated by ophiolite weathering through organic carbon preservation." *Nature Geoscience* 17.1 (2024): 88-93.

Universe Today

Universe Today