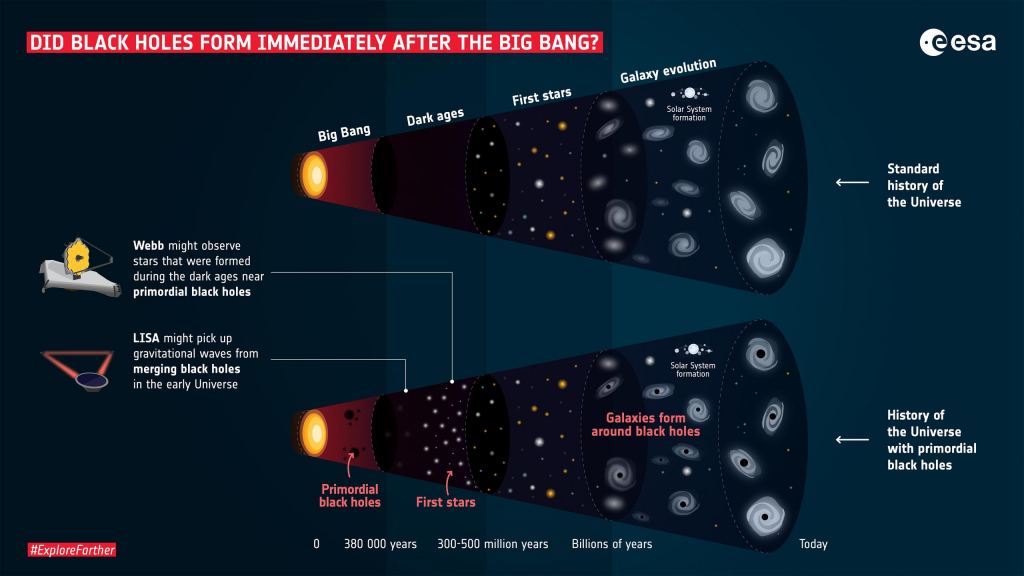

Small primordial black holes (PBHs) are one of the hot topics in astronomy and cosmology today. These hypothetical black holes are believed to have formed soon after the Big Bang, resulting from pockets of subatomic matter so dense that they underwent gravitational collapse. At present, PBHs are considered a candidate for dark matter, a possible source of primordial gravitational waves, and a resolution to various problems in physics. However, no definitive PBH candidate has been observed so far, leading to proposals for how we may find these miniature black holes.

Recent research has suggested that main-sequence neutron and dwarf stars might contain small PBHs in their interiors that are slowly consuming their gas supply. In a recent study, a team of physicists extended this idea to include a new avenue for potentially detecting PBHs. Basically, we could search inside objects like planets and asteroids or employ large plates or slabs of metal to detect PBHs for signs of their passage. By detecting the microchannels these bodies would leave, scientists could finally confirm the existence of PBHs and shed light on some of the greatest mysteries in cosmology today.

The research was conducted by De-Chang Dai, a physicist at National Dong Hwa University in Taiwan and the Center for Education and Research in Cosmology and Astrophysics (CERCA) at Case Western Reserve University, and Dejan Stojkovic, a physicist from High Energy Physics and Cosmology group at the State University of New York Buffalo. The paper that details their findings recently appeared online and is being reviewed for publication in the journal Physics of the Dark Universe.

Scientists have been fascinated by PBHs for decades since Russian scientists Igor D. Novikov and Yakov Zeldovich predicted their existence in 1966. They were also a source of interest for Stephen Hawking, whose work on PBHs led to his breakthrough discovery in 1974 that black holes can evaporate over time. While larger and intermediate black holes would take longer to evaporate than the current age of the Universe (ca. 13.8 billion years), smaller PBHs may have already or could be in the process of doing so.

However, interest in PBHs has experienced a renaissance in recent years because they serve as dark matter candidates, a source of primordial gravitational waves (GWs), and more. Like Dark Matter, their existence could help resolve some major cosmological mysteries, but no confirmed observations have been made yet. As De-Chang and Stojkovic told Universe Today via email, this is what motivated them to propose novel detection methods:

"If an asteroid, or a moon, or a small planet (planetoid) has a liquid core surrounded by a solid crust, then a small PBH will consume the dense liquid core relatively quickly (within weeks to months). The crust will remain intact if the material is strong enough to support gravitational stress. Thus, we will end up with a hollow structure. If the central black hole is ejected (due to collisions with other objects), the density will be lower than the usual density of a rocky object with a liquid core."

In addition, De-Chang and Stojkovic calculated the gravitational stress small PBHs would generate. They then compared this to the compressive strength of materials that make up a planet's crust - such as silicate minerals (rock), iron, and other elements. They also considered the strongest manufactured materials, such as multiwall carbon nanotubes. "We found, for example, that granite can support hollow structures up to the radius of 1/10 of the Earth's radius," said Stojkovic. "That is why we should concentrate on planetoids, moons, or asteroids."

These calculations offer a means to search for evidence of PBHs in space and here on Earth. Possible candidate planetoids, moons, or asteroids could be identified in our Solar System by observing their mass and radius to provide estimates of their density. This would allow astronomers to identify potentially hollow objects for follow-up studies by probes, landers, and other robotic space missions. Alternatively, they recommend that sensors be built to search for PBHs by detecting their passage. Said Stojkovic:

"If a small PBH passes through some solid material, it will leave a straight long tunnel of the radius comparable to the PBH's radius. For example, a 1023g PBH should leave a tunnel with a radius of 0.1 micron. [The energies] that such PBHs can have are significant, but [the energies] which they deposit into the material are very low. In fact, such a PBH can even pass through a human body, and we would not even notice because human body tissue has a very low tension."

In this vein, scientists can scan for micro tunnels in commonplace materials we find lying around (like glass or rocks). At the same time, say De-Chang and Stojkovic, large slabs of polished metal could be prepared for this purpose. Similar to neutrino detection, these slabs would need to be isolated so that any sudden change in their properties could be recorded. "The expected flux of these PBHs is very small and we may end up finding nothing, but a possible payoff of finding a PBHs will be huge, especially since such experiments will be very cheap," said Stojkovic.

As De-Chang added, it has been proposed in recent years that some primordial black holes may be hidden in stars. Stephen Hawking once proposed the idea, which became the basis of two studies, one released in 2019 and another this past year. "It is also proposed that primordial black holes may radiate Gamma rays. Strong gamma rays in the Milky Way's dark matter halo can be a good hint for the existence of primordial black holes," said De-Chang. "Gravitational microlensing can be another way to identify the primordial black holes."

*Further Reading: arXiv*

Universe Today

Universe Today