Testing the equipment on an interstellar mission is one of the first things operators do when the spacecraft successfully launches. In some cases, those tests show the future troubles the mission will face, such as what happened to NASA's Lucy mission a few years ago. However, in some cases, the mission provides us with perspectives we might never have seen before, which was the case for Hera, ESA's mission to Dimorphos. This asteroid was deflected successfully during NASA's DART test in 2022.

Hera was successfully launched on October 7th and carries a series of instruments designed to peer at the asteroids using different wavelengths. Some instruments were turned toward the Earth and Moon from about a million km away as part of the mission's Near-Earth Commissioning Phase. The resulting pictures showcase the spacecraft's capabilities and provide a new perspective of our "terraqueous globe," as Carl Sagan once put it, and our much more sterile neighbor.

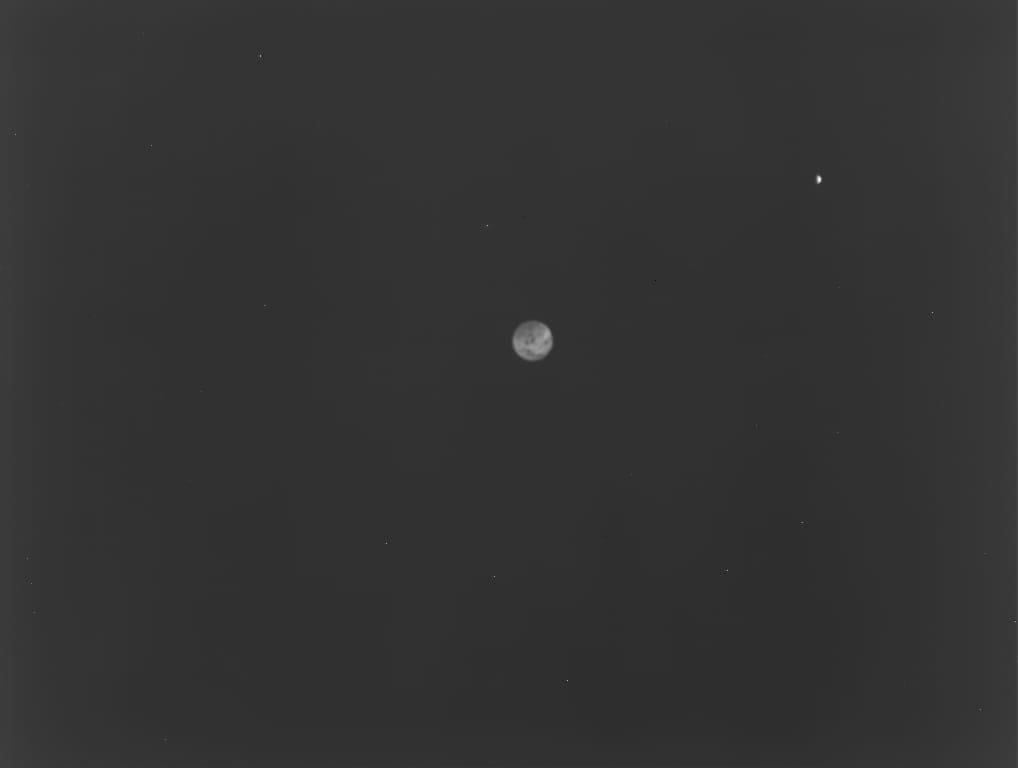

First, we have an image from the Asteroid Framing Camera or AFC. Technically comprised of two cameras (for redundancy, as so many space missions do), this monochrome 1020x1020 image is the clearest of the three released by ESA as part of a press release. It gives a sense of the scale of the distance between the Earth and the Moon, which can be hard to judge when down on the planet's surface.

Next up is the Thermal Infrared Imager, or TIRI. This one was taken slightly closer, at 1.4 million kilometers away (about three times the distance from the Earth to the Moon itself). TIRI is designed to capture infrared wavelengths of light - which we usually think of as heat. Watching Dimorphos over time will allow it to understand the "thermal inertia" of certain regions, which scientists can use to discern some important physical properties of the asteroid. While not the most exciting space image ever captured, the successful operation of this sensitive instrument is critical to the mission.

Finally, there's Hyperscout H. It, too, is designed to capture Dimorphos in wavelengths that humans can't visibly see - in this case, 650 nm to 950 nm wavelengths, which is considered "near infrared" as compared to the "mid-infrared" capabilities of TIRI. Also, this imager comes with its own false color depiction, showing "shorter" wavelengths, which are closer to our visible spectrum, as shades of blue, whereas "reds" represent wavelengths farther away from visible light.

The Earth and Moon have been imaged most likely millions of times in these wavelengths before, so it's unlikely that any science will be gleaned from these images. Still, these images are invaluable as proof of concept for the operation of the systems. The three cameras comprise some of the essential parts of Hera's "asteroid deck," which houses most of the spacecraft's other instruments, including two CubeSat deployers, a laser rangefinder, and antennas for deep-space communication with Earth. Many of those different instruments will have to wait until "show time" when the craft arrives at the binary asteroid system in December 2026. Hopefully, we will also receive plenty more images from the three systems covered here.

Learn More:

ESA - Hera’s first images offer parting glimpse of Earth and Moon

UT - Hera Probe Heads Off to See Aftermath of DART’s Asteroid Impact

UT - ESA’s Hera Mission is Bringing Two Cubesats Along. They’ll Be Landing on Dimorphos

UT - The Smallest Radar Ever Sent to Space Will Probe the Interior of Dimorphos After its Impact From DART

Lead Image:

Image of Earth from the AFC

Credit - ESA

Universe Today

Universe Today