Most of us know about the impact that wiped out the dinosaurs about 66 million years ago. It's a scientific fact that's entered mainstream knowledge, maybe because so many of us shared a fascination with dinosaurs as children. However, it's not the only catastrophic impact that shaped life on Earth.

There was an even more ancient one about 3.26 billion years ago, and its repercussions shaped early life in a unique way.

The impact event is called S2, and it took place during Earth's Archean Eon. The Archean is the second of Earth's four geological eons, spanning from 4,031 to 2,500 Mya (million years ago). A series of significant changes took place during the Archean, including the formation of Earth's crust, the emergence of the first continents, and the development of a reducing atmosphere suitable for the first simple lifeforms.

When the S2 impactor struck, Earth life was simple and microbial. The impact had a powerful effect on our planet's early living things, and new research examines what happened. It's titled " Effect of a giant meteorite impact on Paleoarchean surface environments and life," and it's published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The lead author is Nadja Drabon, an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Harvard University.

"We think of impact events as being disastrous for life," Drabon said. "But what this study is highlighting is that these impacts would have had benefits to life, especially early on … these impacts might have actually allowed life to flourish."Nadja Drabon, Dept. of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard.

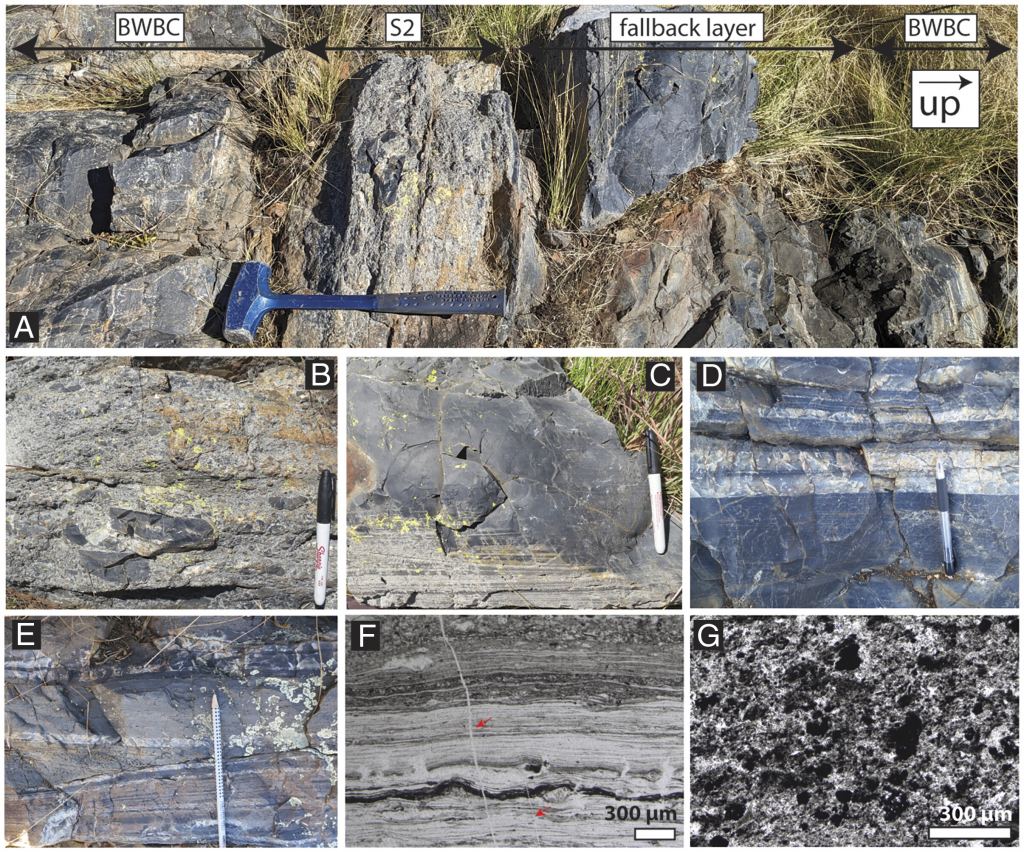

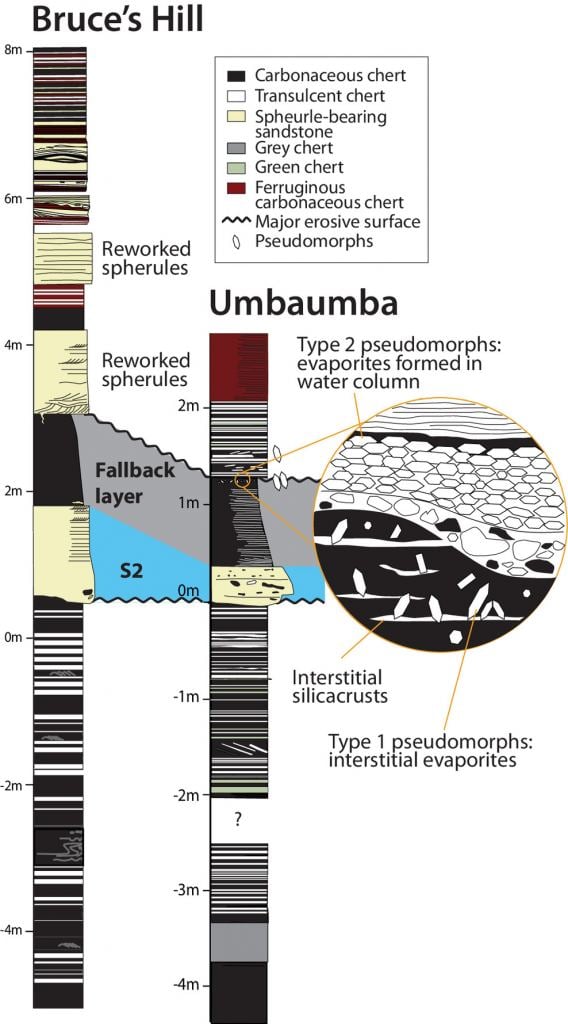

Drabon and her fellow researchers performed painstaking, detailed work to get their results. They travelled to the Barberton Greenstone Belt in South Africa to do their fieldwork. The Belt contains some of the oldest exposed rocks on Earth, and those rocks hold some of the oldest traces of life on Earth. Barberton also holds evidence of at least eight ancient impacts, including S2. Drabon and her team examined rock samples centimetres apart and analyzed their geochemistry, sedimentology, and carbon isotope compositions.

They were able to paint a picture of the momentous day over three billion years ago when an extremely large carbonaceous chondrite 37-58 km in diameter, or 200 times larger than the dinosaur-killing Chicxulub impactor, struck Earth.

It started with a tsunami.

"Picture yourself standing off the coast of Cape Cod, in a shelf of shallow water. It's a low-energy environment without strong currents. Then all of a sudden, you have a giant tsunami, sweeping by and ripping up the sea floor," said Drabon.

The ocean was mixed up, and the tsunami carried debris from the land into the oceans. The catastrophic impact generated an enormous amount of heat, boiling away the uppermost layer of the ocean and heating the atmosphere. Next came a thick cloud of dust that prohibited any photosynthesis.

This was a dismal yet brief period in Earth's history. But life has repeatedly shown how resilient it is. Earth's primitive bacteria quickly bounced back from the cataclysm.

The impact stirred up iron and mixed deep Fe²+-rich waters with shallow Fe²+-poor waters. Fe²+is an essential nutrient, and along with phosphorous released from the vaporized meteorite and increased weathering from the tsunami, these two nutrients fuelled life's rebound.

According to the researchers' analysis, all of this iron triggered a great flourishing of iron-metabolizing bacteria. This bias toward iron-loving life didn't last, however, and equilibrium eventually returned. But the event is still a key piece in the puzzle of life on Earth. Despite the cataclysmic effect of giant impacts, they can provide some benefits. (There's some evidence that meteorites delivered the building blocks of life to Earth.)

"The recovery of life would have been fueled by an increase in ferrous iron in the photic zone and enhanced nutrient (especially phosphorous) availability, both indicated by geochemical data," the authors explain in their research.

"We think of impact events as being disastrous for life," Drabon said. "But what this study is highlighting is that these impacts would have had benefits to life, especially early on … these impacts might have actually allowed life to flourish."

The researchers say that events immediately following the impact followed a tight timeline. The heat melted rock into spherules, and they were deposited just before or concurrent with the tsunami deposit. After the spherules and tsunami debris settled, the fallback layer quickly formed. That layer consists of rock lofted into the air by the impact.

"Altogether, the spherule beds and fallback deposits (1.3 to 5 m of strata) were likely deposited within no more than a few days—a geological instant," the authors write in their research. "In this limited time period, the impact-initiated tsunami ripped up the sea floor, disturbed coastal benthic biosystems, mixed the water column, washed debris from coastal areas into the sea, and caused turbid conditions."

S2, and probably other large impacts during the early Archean, seem to have had mixed effects on life. For some, the increased nutrients were a boon; for others, the thick dust cloud inhibited photosynthesis. "The tsunami, ocean evaporation, and darkness most severely affected phototrophs in surface waters, but chemoautotrophs in the lower water column and hyperthermophiles would likely have been less influenced," the authors explain.

Other research into S2 suggests that the impact had other effects. Several studies suggest that it triggered volcanic activity. It may have also generated hydrothermal fields at the impact site, which could have added additional Fe²+ to the environment. It may even have generated tectonic activity.

S2 is just one example of the impacts that shaped life's trajectory on Earth. Archean rocks contain evidence of at least 16 ancient impacts with bolides larger than 10 km. All of these likely generated severe though short-lived effects.

"Our work suggests that on a global scale, early life may have benefitted from an influx of nutrients and electron donors, as well as new environments, as a result of major impact events," the researchers conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today