Moons are the norm in our Solar System. The International Astronomical Union recognizes 288 planetary moons, and more keep being discovered. Saturn has a whopping 146 moons. Every planet except Mercury and Venus has moons, and their lack of moons is attributed to their small size and proximity to the Sun.

It seems reasonable that there are moons around exoplanets in other Solar Systems, and now we're going to start looking for them with the James Webb Space Telescope.

The Cool Worlds Lab is part of the Columbia University Astronomy Department and is led by assistant professor David Kipping, a well-known British/American astronomer. The Lab focuses on cool exoplanets with wide orbits around stars. "In this regime, orbital dynamics and atmospheric chemistry diverge from their hot counterparts, and the potential for satellites, rings, and habitability become enhanced," the Lab's website says. Exomoons around these planets are part of the Lab's focus, and Kipping is an author and co-author of several papers about exomoons.

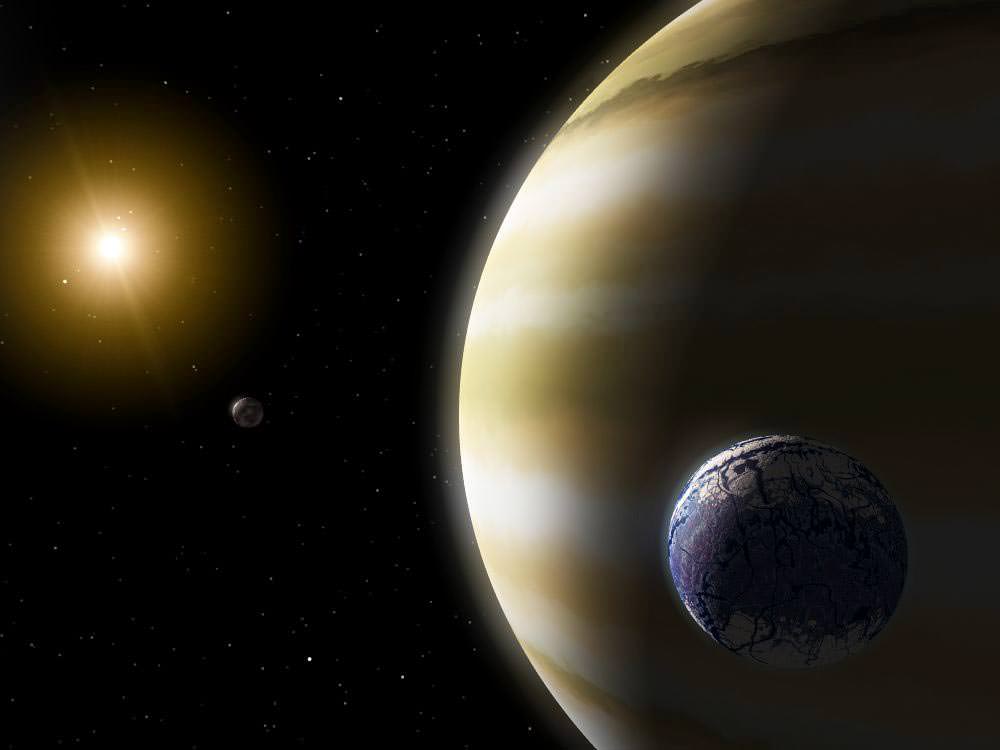

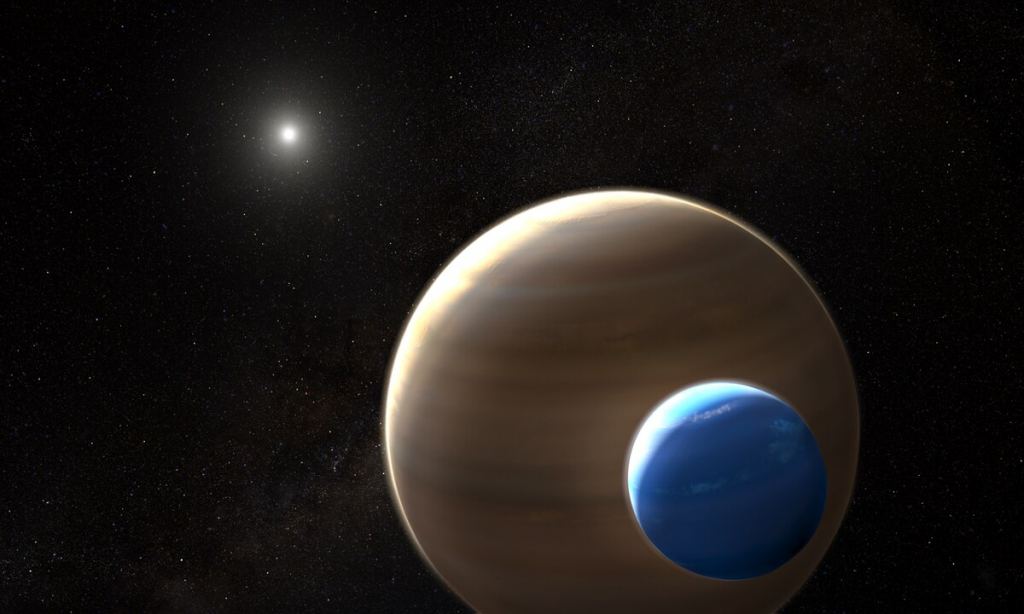

There's a lot of active discussion in the astronomy world about exomoons, how to find them, and how to confirm them. Currently, there are no confirmed exomoons, only a list of candidates, some of which should be in habitable zones if they're real.

Kipping and his team have succeeded in getting some JWST observation time to look for an exomoon. Back in February, his proposal was selected. "We have been hoping to find exomoons for a very long time," Kipping says in a YouTube video announcing the beginning of their JWST observations, adding that exomoons have been "a continuous thread in my career."

Now, Kipping and the Cool Worlds Lab is being given a chance to use the world's most powerful space telescope to observe an exoplanet named Kepler-167e. Kipping himself found this planet about 10 years ago, and there's something special about it. It's a Jupiter analogue and a very rare example of a long-period transiting gas giant. Because Jupiter has so many moons, Kipping and others argue that Kepler-167e is a strong candidate to also have moons.

The planet only transits its star once every three years, and the next transit is happening right now. In fact, it started yesterday morning, and the JWST was watching on behalf of the Cool Worlds Lab. The JWST has given the Lab 60 hours—2 and a half days— of observing time. Those observations are happening right now, and if all goes well, we may have our first strong detection of an exomoon.

The data from these observations is exclusive to the Cool Worlds Lab for one year. "We have a year before the data goes public, and that's fairly normal with JWST data," Kipping said.

Kipping says they have to be cautious when they get their initial results. "I've been in this situation many times. You get the data on the first day. You see a dip and you're like 'That's it. We're there. We've got a moon.' " But a few weeks or months later, it could turn out to not be real. "So we don't want to get people's excitement up prematurely," he said.

Looking for exomoons is extremely challenging and Kipping led an effort to find some in Kepler's data. "We surveyed probably on the order of 300 or 350 exoplanets during our time, and only two real candidates popped up over this entire analysis," Kipping said in an

Kipping told Universe Today that "we're really pushing these data sets to their limits to even get these signals."

But the JWST's data should be more robust than Kepler's. Kepler was an automated survey, while the JWST is a different beast. Kepler had a fixed field of view and a primary mirror only 0.95 meters in diameter. Its sole job was to detect exoplanets that transited in front of their stars. The JWST has a 6.5-meter mirror, multiple instruments, including cameras and spectrographs, and a system of filters. It's far more capable than Kepler, as almost everyone knows.

Kipping is hopeful that the JWST will be able to detect moons as small as Ganymede and Callisto. There's a chance that the JWST will detect a slam-dunk exomoon and that it'll be clear to everyone. "That's the dream scenario," Kipping says. However, this set of observations will be scientifically rich whether they detect an exomoon or not because the JWST will be able to measure other things about the planet.

"But there's also a scenario where we don't see anything," Kipping said. If that happens, it would also be a significant finding. "We would essentially have to rip up the textbook," Kipping said. "If we don't see a Titan, if we don't see a Ganymede, we don't see a Callisto, that is telling us something quite profound about Moon formation, maybe that our Solar System's kind of special."

This mirrors what we used to say about exoplanets. Prior to the Kepler mission, which found over 2,500 exoplanets, we weren't certain if our Solar System's planet population was normal or extraordinary. Now we know that exoplanets are likely orbiting every star. (Though our Solar System is still special.)

We may be on the verge of an age of exomoon discovery, just as we were prior to Kepler's launch. The Cool Worlds Lab exomoon observations are just one of five exomoon observing efforts the JWST has approved, and the JWST isn't the only telescope that will be searching for them. The ESA's upcoming PLATO (PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars) mission will study exoplanets in habitable zones around Sun-like stars, and it will also discover exomoons.

Kipping is boiling over with enthusiasm about the JWST's observations of Kepler-167e. He discovered the planet, and if he and his team were able to find the first confirmed exomoon around it, it would be quite an achievement.

"It's an amazing opportunity that we have to potentially test some long-standing theories," Kipping said, adding that it's also a "dream I've had for my entire career."

For updates on the observations, follow Cool Worlds on YouTube.

Universe Today

Universe Today