Subsurface oceans of liquid water are a common feature of the moon's of Jupiter and Saturn. Researchers are exploring whether the icy moons of Uranus and Neptune might have them as well. Their new paper suggests future missions to the outer Solar System could measure the rotation of the moons and detect any wobbles pointing to liquid oceans. Less wobble means the moons is mostly solid but large wobbles can indicate ice floating on an ocean of liquid.

Uranus is the 7th planet in the Solar System, classed as an ice giant and measures 50,724 km across. It has 27 known moons each of which have very unique and distinct characteristics. They tend to be categorised into three different groups; large moons, small inner moons and those which are irregular outer moons. The largest moon of Uranus is Titania which is composed broadly of equal parts rock and ice. The surface has a mix of old craters and younger geological features, fault lines and even cryovolcanism.

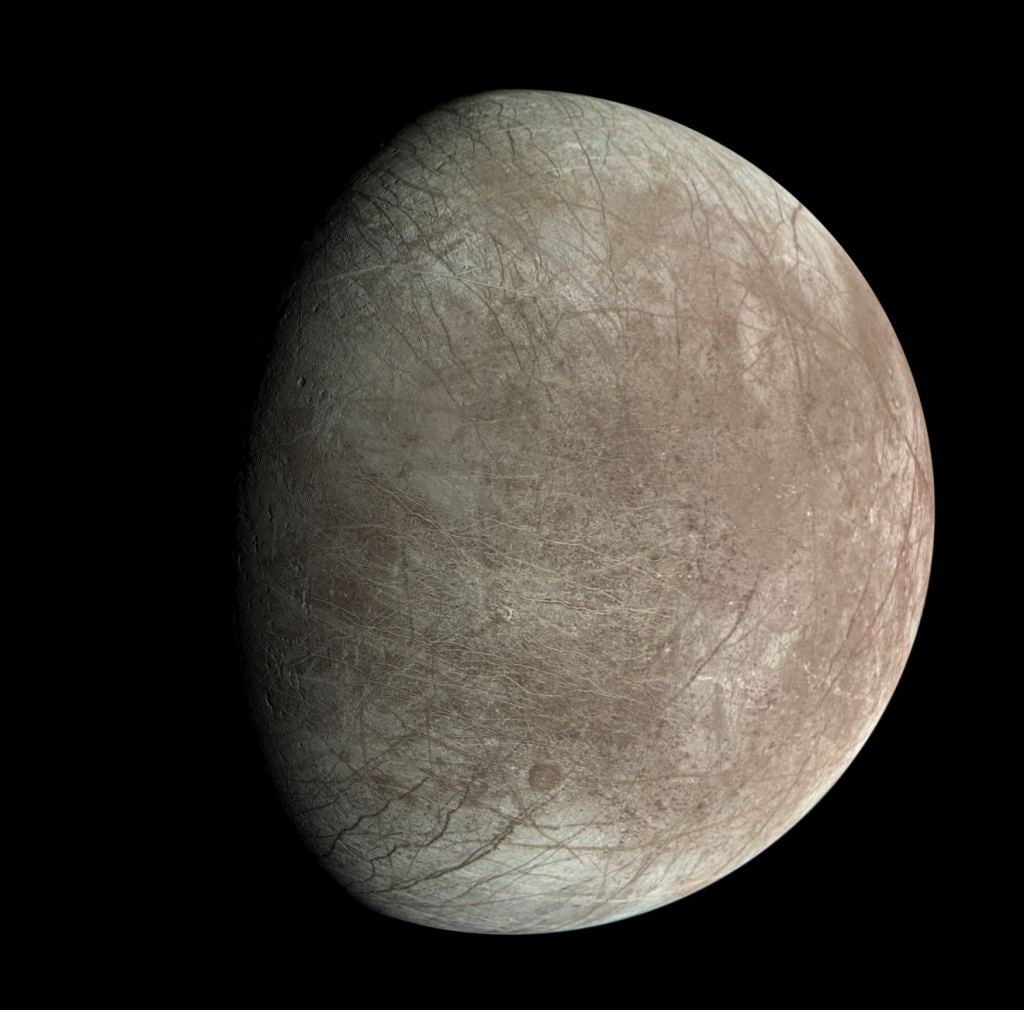

Icy moons are fascinating to explore largely because of the potential for finding life! Jupiter's moon Europa is a great example. Beneath the icy crust which is 30 km thick exists an ocean thought to be 100 km deep. The ocean is kept liquid by internal heat generated from the tidal interactions with Jupiter. It's hypothesised that subsurface oceans like these may harbour life. On Earth we have found life in the deepest crevices of our oceans, drawing energy not from sunlight but from hydrothermal vents. Such features may well exist on Europa and other icy moons making them great places to detect life.

Much has been learned about the outer Solar System largely from the Voyager and Pioneer probes. Exploring the region nearly 40 years ago, the probes were equipped with fairly limited imaging systems. NASA is now planning on sending another probe to Uranus with better technology and learn more about its icy moons.

A team of researchers based at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics are gearing up for the mission by developing a technique to detect subsurface oceans using only cameras! Their approach relies upon capturing high resolution images of the moons an analysing them for any wobbles as the moon spins.

From this information, it's possible to work out how much ice, water and rock is inside. If the wobble is only slight then it's likely the interior of the moon is solid whereas a much larger amplitude to the wobble could mean ice is floating around on a subsurface ocean. In reality a large wobble only means movement of under 100 metres. This is within the capability of modern technology to detect.

The technique that has been developed by planetary scientist Doug Hemingway and team has been run through some theoretical calculations. They found that for example, if Ariel wobbles by about 100 metres then it is likely to have an ocean 160 km thick surrounded by an ice shell around 30 km thick. Smaller oceans are detectable but the work the team have undertaken will help give mission designers guidelines to maximise the outcome of the scientific goals.

Source : Uranus’s swaying moons will help spacecraft seek out hidden oceans

Universe Today

Universe Today