Popular media love talking about asteroid mining using big numbers. Many articles talk about a mission to Psyche, the largest metallic asteroid in the asteroid belt, as visiting a body worth $10000000000000000000, assumedly because their authors like hitting the “0” key on their keyboards a lot. But how realistic is that valuation? And what does it actually mean? A paper funded by Astroforge, an asteroid mining start-up based in Huntington Beach, and written by a professor at the Colorado School of Mine’s Space Resources Program takes a good hard look at what metals are available on asteroids and whether they’d genuinely be worth as much as the simple calculations say that would be.

The paper divides metals on asteroids into two distinct types—those that would be worth returning to Earth and those that wouldn’t. Really, the only metals judged to be worthy of returning to Earth are the platinum-group metals (PGMs), which are known for their extraordinarily high cost, relatively low supply, and high usefulness in a variety of modern-day technology. That includes catalytic converters, which is why they are commonly the target of thieves.

The other category would be metals used for in-space construction, such as iron, aluminum, and magnesium. While these might not be economically viable to send back to Earth because of their relatively low prices on our home planet, they are useful up in space for constructing large structures, such as space stations or solar power arrays. However, given the chicken-and-egg problem of not having any demand for these space-sourced metals because they are so expensive, it is hard to quantify how much they are worth. Its competition (i.e. launching the material from Earth), is priceable though, and at $10,000 / kg, plus $100 / kg for a common material such as iron.

Those prices aren’t anywhere near the $500,000 / kg that a PGM such as Rhodium has ever back on Earth, but it could still make mining asteroids for iron economically viable if the material is used in space. So what do all those calculations mean for the actual value of the asteroids that we might mine?

First and most importantly, recent research suggests that asteroids made out of “pure metal,” such as Psyche is assumed to be, are likely pure fiction. While that might not be great news for any single benign asteroid worth a lot, the other part of that research is that even asteroids that were originally thought to be relatively low in metal content actually have reasonable quantities that could be economically extracted.

To prove the point, the paper looked in detail at a series of meteorite studies, which are the equivalent of left-over asteroids, and compared the “grades” of 83 different elements with ores found on or near the Earth’s surface. Since remote sensing has difficulty distinguishing between some of those elements, meteorite samples that can be subjected to advanced analysis techniques are our best bet at accurately calculating the chemical composition of asteroids, other than the few samples of in-tact asteroids that have been returned so far.

Credit – Isaac Arthur YouTube Channel

That data showed that PGMs, while lower in concentration than considered initially (because of an assumption in a foundational paper on the composition of asteroids), are still in much higher concentrations than the equivalent terrestrial ores. In particular, a material known as a refractory metal nugget (RMN) could have concentrations of PGMs orders of magnitude higher than anything found on Earth or other types of asteroidal material.

RMNs are primarily found in a calcium aluminum inclusion (CAI) structure, mainly on L-type asteroids. L-types are relatively uncommon asteroids with a reddish tint, but we haven’t yet visited them. They might be made up of more than 30% CAIs, though, in which case, they could contain a significant amount of extractable PGMs without additional processing.

However, RMNs themselves are very small, at the micron to sub-micron range, making them extremely hard to process in the first place. So, bulk extraction from asteroidal regolith could range up to hundreds of ppm, which is already a few orders of magnitude greater than their concentration in Earth’s regolith.

When looking at the metals for use in space, they are about as abundant as initially predicted, but they face challenges in processing them out of their oxidized states. Typically, this requires some high-energy procedure, such as molten regolith electrolysis, to break off the elemental metal, which is needed for further processing. Again, there’s the chicken and egg problem of having a power source that is large enough to perform these processes, but building it would require the material that would require the power source.

Eventually, that problem will disappear if companies like AstroForge have their way. Remember that the company funded this study, and its two co-founders and Kevin Cannon, the professor at CSM, were co-authors. The company plans to launch its next mission, a rendezvous with near-Earth asteroids, to try to tell if they’re “metallic” in January. Perhaps that mission will help contribute to our growing understanding of the composition and value of the asteroids surrounding us.

Learn More:

Cannon, Gialich, Acain – Precious and structural metals on asteroids

UT – What Are Asteroids Made Of?

UT – What Is The Difference Between Asteroids and Meteorites?

UT – Asteroids: 10 Interesting Facts About These Space Rocks

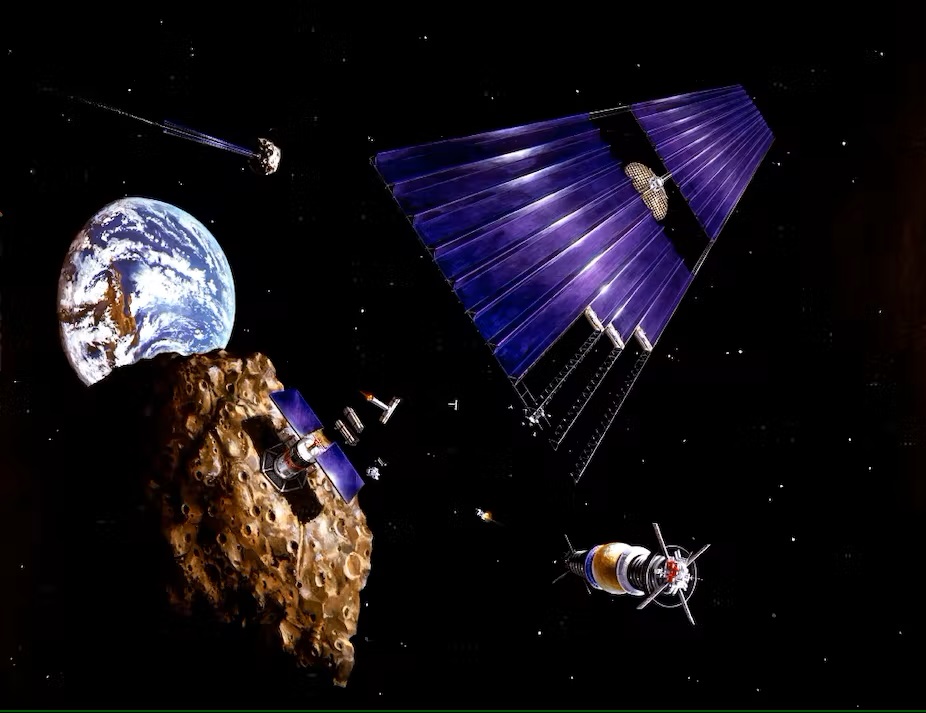

Lead Image:

Asteroid mining concept.

Credit: NASA/Denise Watt