The James Webb Space Telescope* (JWST) was specifically intended to address some of the greatest unresolved questions in cosmology. These include all of the major questions scientists have been pondering since the Hubble Space Telescope* (HST) took its deepest views of the Universe: the Hubble Tension, how the first stars and galaxies came together, how planetary systems formed, and when the first black holes appeared. In particular, Hubble spotted something very interesting in 2003 when observing a star almost as old as the Universe itself.

Orbiting this ancient star was a massive planet whose very existence contradicted accepted models of planet formation since stars in the early Universe did not have time to produce enough heavy elements for planets to form. Thanks to recent observations by the JWST, an international team of scientists announced that they may have solved this conundrum. By observing stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud (LMC), which lacks large amounts of heavy elements, they found stars with planet-forming disks that are longer-lived than those seen around young stars in our Milky Way galaxy.

The study was led by Guido De Marchi, an astronomer at the European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC) in Noordwijk, Netherlands. He was joined by researchers from the INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Gemini Observatory/NSF NOIRLab, the UK Astronomy Technology Centre (UK ATC), the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Edinburgh, the Leiden Observatory, the European Space Agency (ESA), NASA's Ames Research Center, and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The paper detailing their findings appeared on December 16th in The Astrophysical Journal.

According to accepted cosmological models, the first stars in the Universe (Population III stars) formed 13.7 billion years ago, just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang. These stars were very hot, bright, massive, short-lived, and composed of hydrogen and helium, with very little in the way of heavy elements. These elements were gradually forged in the interiors of Population III stars, which distributed them throughout the Universe once they exploded in a supernova and blew off their outer layers to form star-forming nebulae.

These nebulae and their traces of heavier elements would form the next generation of stars (Population II). After these stars formed from gas and dust in the nebula that underwent gravitational collapse, the remaining material fell around the new stars to form protoplanetary disks. As a result, subsequent populations of stars contained higher concentrations of metals (aka. metallicity). The presence of these heavy elements, ranging from carbon and oxygen to silica and iron, led to the formation of the first planets.

As such, Hubble 's discovery of a massive planet (2.5 times the mass of Jupiter) around a star that existed just 1 billion years after the Big Bang baffled scientists since early stars contained only tiny amounts of heavier elements. This implied that planet formation began when the Universe was very young, and some planets had time to become particularly massive. Elena Sabbi, the chief scientist for the Gemini Observatory at the National Science Foundation's NOIRLab, explained in a NASA press release:

"Current models predict that with so few heavier elements, the disks around stars have a short lifetime, so short in fact that planets cannot grow big. But Hubble did see those planets, so what if the models were not correct and disks could live longer?"

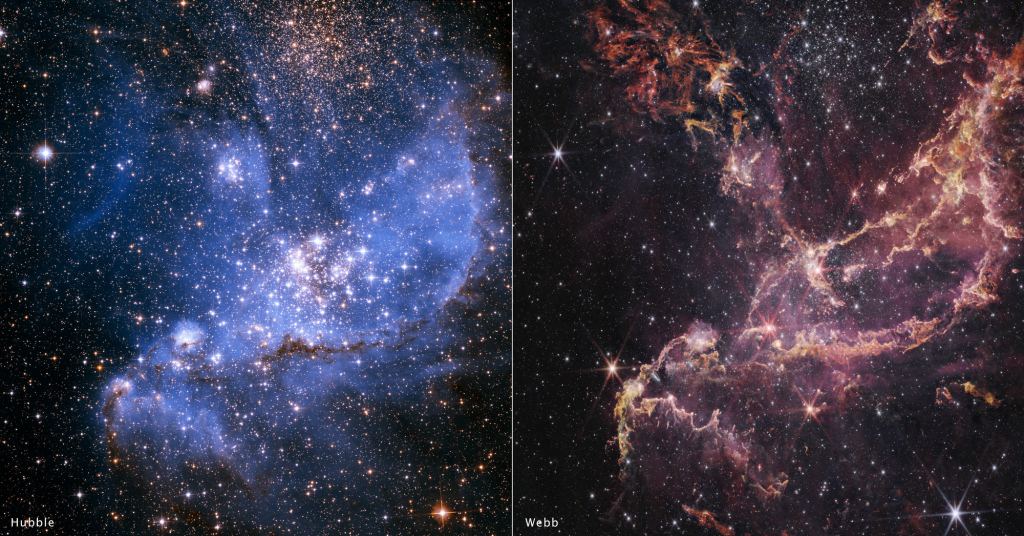

To test this theory, the team used Webb to observe the massive, star-forming cluster NGC 346 in the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy and one of the Milky Way's closest neighbors. This star cluster is also known to have relatively low amounts of heavier elements and served as a nearby proxy for stellar environments during the early Universe. Earlier observations of NGC 346 by Hubble revealed that many young stars in the cluster (~20 to 30 million years old) appeared to still have protoplanetary disks around them. This was also surprising since such disks were believed to dissipate after 2 to 3 million years.

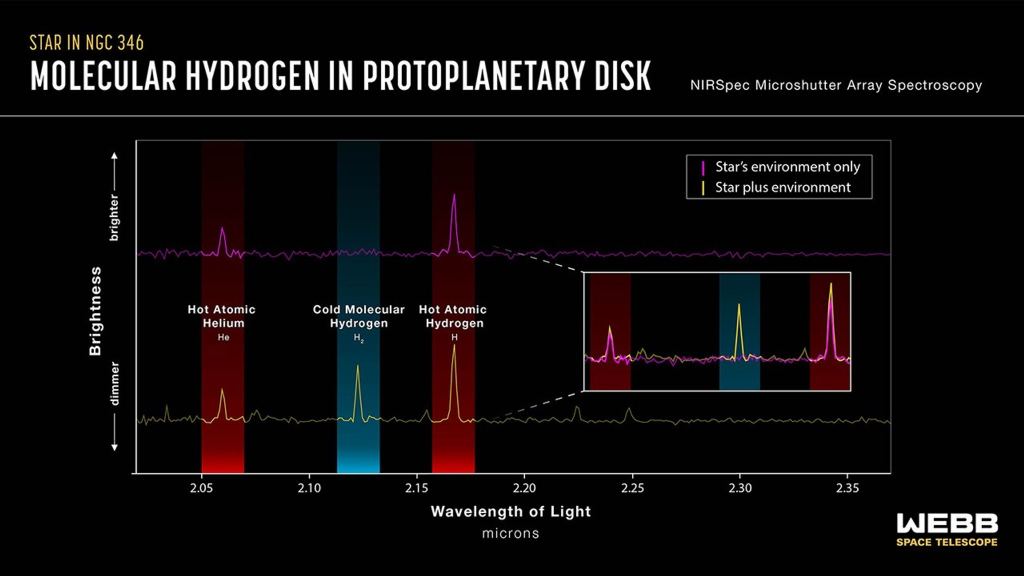

Thanks to Webb 's high-resolution and sophisticated spectrometers, scientists now have the first-ever spectra of young Sun-like stars and their environments in a nearby galaxy. As study leader Guido De Marchi of the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk put it:

"The Hubble findings were controversial, going against not only empirical evidence in our galaxy but also against the current models. This was intriguing, but without a way to obtain spectra of those stars, we could not really establish whether we were witnessing genuine accretion and the presence of disks, or just some artificial effects." "We see that these stars are indeed surrounded by disks and are still in the process of gobbling material, even at the relatively old age of 20 or 30 million years. This also implies that planets have more time to form and grow around these stars than in nearby star-forming regions in our own galaxy."

These findings naturally raise the question of how disks with few heavy elements (the very building blocks of planets) could endure for so long. The researchers suggested two distinct mechanisms that could explain these observations, alone or in combination. One possibility is that a star's radiation pressure may only be effective if elements heavier than hydrogen and helium are present in sufficient quantities in the disk. However, the NGC 346 cluster only has about ten percent of the heavier elements in our Sun, so it may take longer for a star in this cluster to disperse its disk.

The second possibility is that where heavier elements are scarce, a Sun-like star would need to form from a larger cloud of gas. This would also produce a larger and more massive protoplanetary disk, which would take longer for stellar radiation to blow away. Said Sabbi:

"With more matter around the stars, the accretion lasts for a longer time. The disks take ten times longer to disappear. This has implications for how you form a planet, and the type of system architecture that you can have in these different environments. This is so exciting."

"With Webb, we have a really strong confirmation of what we saw with Hubble, and we must rethink how we model planet formation and early evolution in the young universe," added Marchi.

Like many of Webb's observations, these findings are a fitting reminder of what the next-generation space telescope was designed to do. In addition to confirming the Hubble Tension, the JWST observed more galaxies (and bigger ones!) in the early Universe than models predicted. It also observed that the seeds of Supermassive Black Holes (SMBH) were more massive than expected. In this respect, the JWST is doing its job by causing astronomers to rethink theories that have been accepted for decades. From this, new theories and discoveries will follow that could upend what we think we know about the cosmos.

Further Reading: NASA*, The Astrophysical Journal*

Universe Today

Universe Today