Astrophotography is a challenging art. Beyond the usual skill set of understanding things such as light exposure, color balance, and the quirks of your kit, there is the fact that stars are faint and they move.

Technically, the stars don't move; the Earth rotates. But to capture a faint object, you need a long exposure time. Typically, from a few seconds to half a minute, depending on the level of detail you want to capture. In thirty seconds, the sky will shift by more than a tenth of a degree. That might not seem like much, but it's enough to make the stars blur ever so slightly. Many astrophotographers take multiple images and stack them for even greater detail, which would blur things even more. It can create an interesting effect, but it doesn't give you a panorama of pinpoint stars.

Fortunately, there is plenty of off-the-shelf equipment you can get to account for motion blur. There are tracking motors you can mount to your camera that move your frame in time with the Earth's rotation. They are incredibly precise so that you can capture image after image for hours, and your camera will always be perfectly aligned with the sky. If you make your images into a movie, the stars will remain fixed while the Earth rotates beneath them.

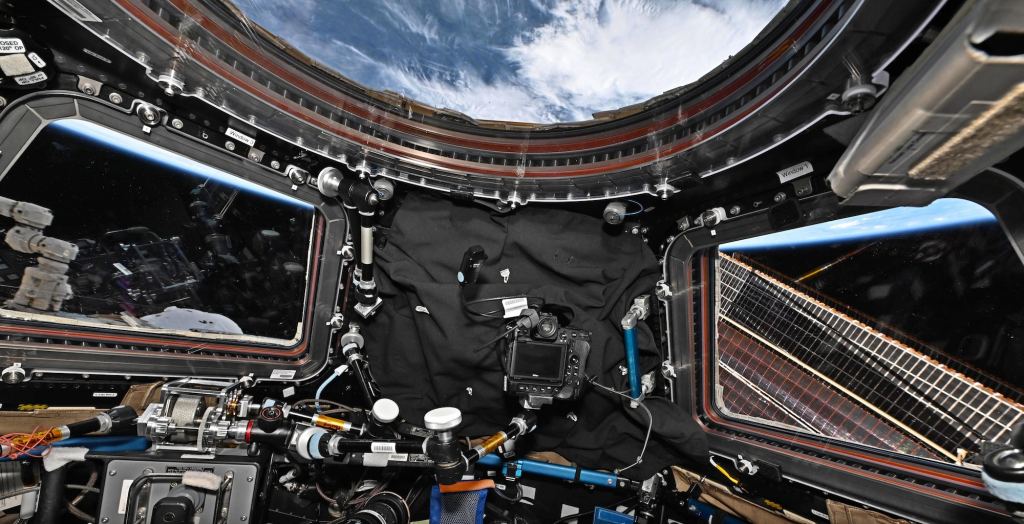

Of course, most astrophotographers have the same limitations of almost everyone. We are bound to the Earth and can only view the stars through our blanket of sky. If we could rise above the atmosphere, we would have an unburdened view of the heavens. A sky filled with uncountable, untwinkling stars. While astronauts often talk about this wondrous sight, photographs of stars from orbit are often less than spectacular. That's because of how difficult astrophotography is in space, and it all comes back to motion blur.

Most astrophotography is done from the International Space Station (ISS). Since the ISS is in a relatively low orbit, it travels around the Earth once every 90 minutes. This means the stars appear to drift at a rate 16 times faster than they do on Earth. A 30-second exposure on the ISS has greater motion blur than an eight minute exposure on Earth. Because of this, most photographs from the ISS either have blurry stars or only capture the brightest stars.

Ideally, an astronaut astrophotographer would bring along a camera mount similar to the ones used on Earth. But the market demand for such a mount is tiny, so you can't just buy one from your local camera store. You have to make your own, which is precisely what astronaut Don Pettit did. Working with colleagues from RIT, he created a camera tracker that shifts by 0.064 degrees per second and can be adjusted give or take 5%. With this mount, Don has been able to capture 30-second exposures with almost no motion blur. His images rival some of the best Earth-based images, but he takes them from space!

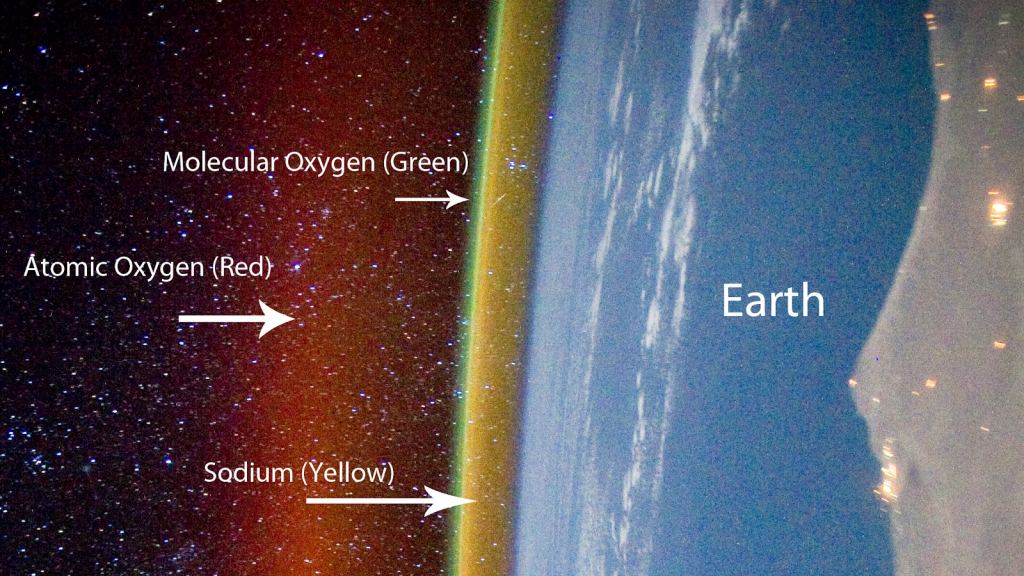

The detail of his photographs is unprecedented. In the image above, for example, you can see the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, and not just as fuzzy patches in the sky. You can see individual stars within the clouds. The image also gives an excellent view of an effect known as airglow. Molecules in the upper atmosphere are ionized by sunlight and cosmic rays, which means this layer always has a faint glow to it. No matter how skilled a terrestrial astrophotographer is, their images will always have a bit of this glow.

But not Don Pettit. He's currently on the ISS, capturing outstanding photographs as a side hobby from his day job. If you want to see more of his work, check him out on Reddit, where he posts under the username astro_pettit.

Universe Today

Universe Today