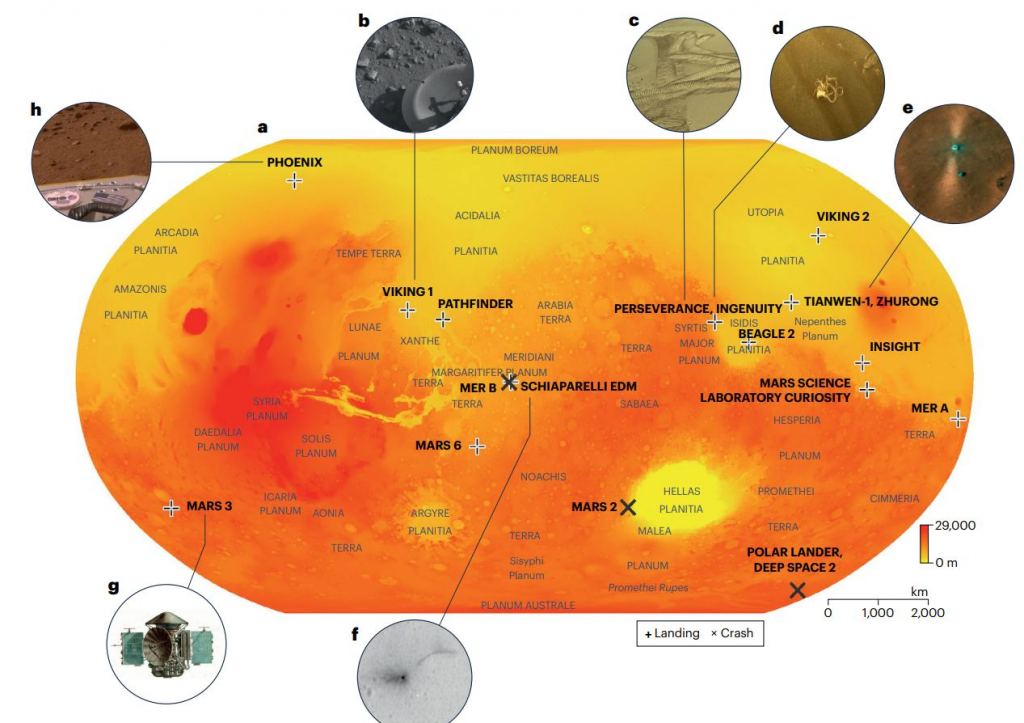

In 1971, the Soviet Mars 3 lander became the first spacecraft to land on Mars, though it only lasted a couple of minutes before failing. More than 50 years later, it's still there at Terra Sirenum. The HiRISE camera NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter may have imaged some of its hardware, inadvertently taking part in what could be an effort to document our Martian artifacts.

Is it time to start cataloguing and even preserving these artifacts so we can preserve our history?

Some anthropologists think so.

Justin Holcomb is an assistant research professor of anthropology at the University of Kansas. He and his colleagues argue that it's time to take Martian archaeology seriously, and the sooner we do, the better and more thorough the results will be. Their research commentary, " The emerging archaeological record of Mars, " was recently published in Nature Astronomy.

Artifacts of the human effort to explore the planet are littered on its surface. According to Holcomb, these artifacts and our effort to reach Mars are connected to the original human dispersal from Africa.

"Our main argument is that Homo sapiens are currently undergoing a dispersal, which first started out of Africa, reached other continents and has now begun in off-world environments," said lead author Holcomb. "We've started peopling the solar system. And just like we use artifacts and features to track our movement, evolution and history on Earth, we can do that in outer space by following probes, satellites, landers and various materials left behind. There's a material footprint to this dispersal."

It's tempting to call debris from failed missions wreckage or even space junk like we do the debris that orbits Earth. But things like spent parachutes and heat shields are more than just wreckage. They're artifacts the same way other cast-offs are artifacts. In fact, what archaeologists often do in the field is sift through trash. "Trash is a proxy for human behaviour," said one anthropologist.

In any case, one person's trash can be another person's historical artifact.

"These are the first material records of our presence, and that's important to us," Holcomb said. "I've seen a lot of scientists referring to this material as space trash, galactic litter. Our argument is that it's not trash; it's actually really important. It's critical to shift that narrative towards heritage because the solution to trash is removal, but the solution to heritage is preservation. There's a big difference."

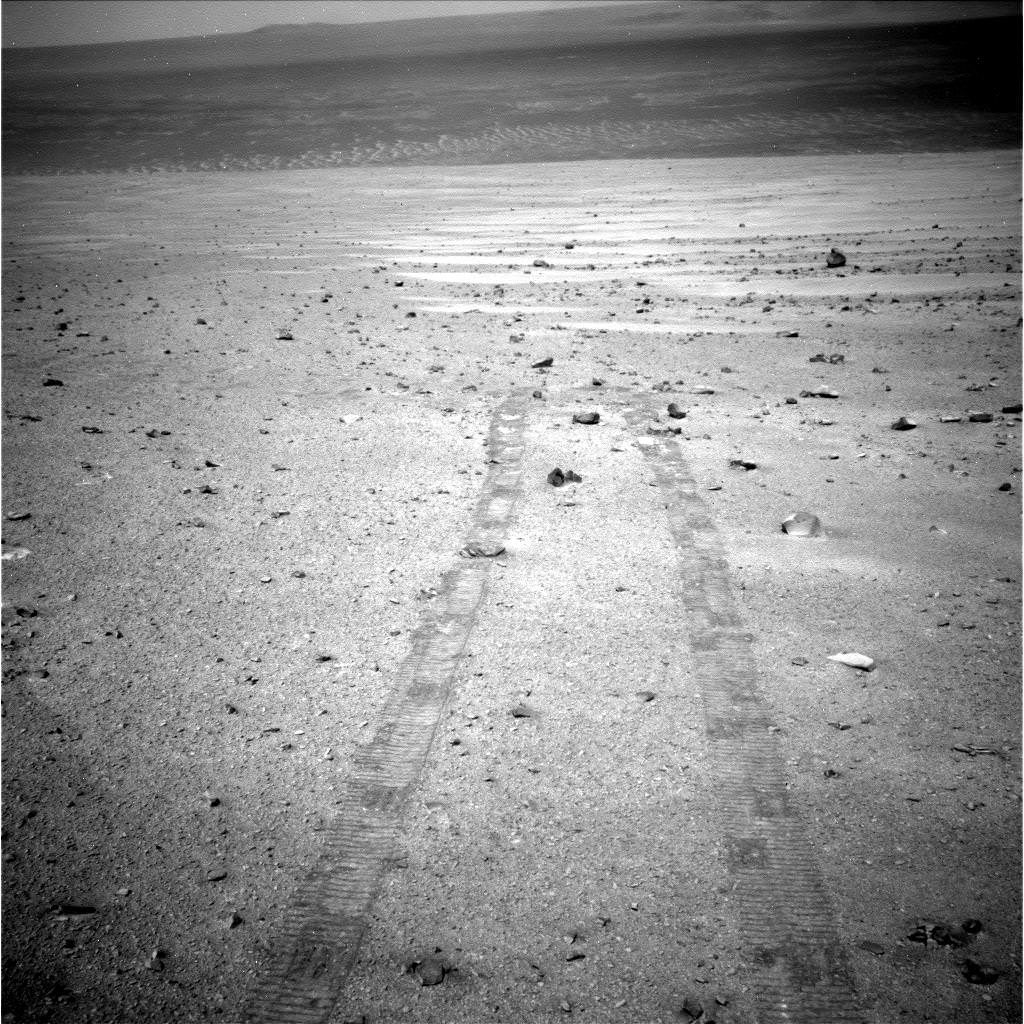

14 missions to Mars have left their mark on the red planet in the form of artifacts. According to the authors, this is the beginning of the planet's archaeological record. "Archaeological sites on the Red Planet include landing and crash sites, which are associated with artifacts including probes, landers, rovers and a variety of debris discarded during landing, such as netting, parachutes, pieces of the aluminum wheels (for example, from the Curiosity rover), and thermal protection blankets and shielding," they write.

Other features include rover tracks and rover drilling and sampling sites.

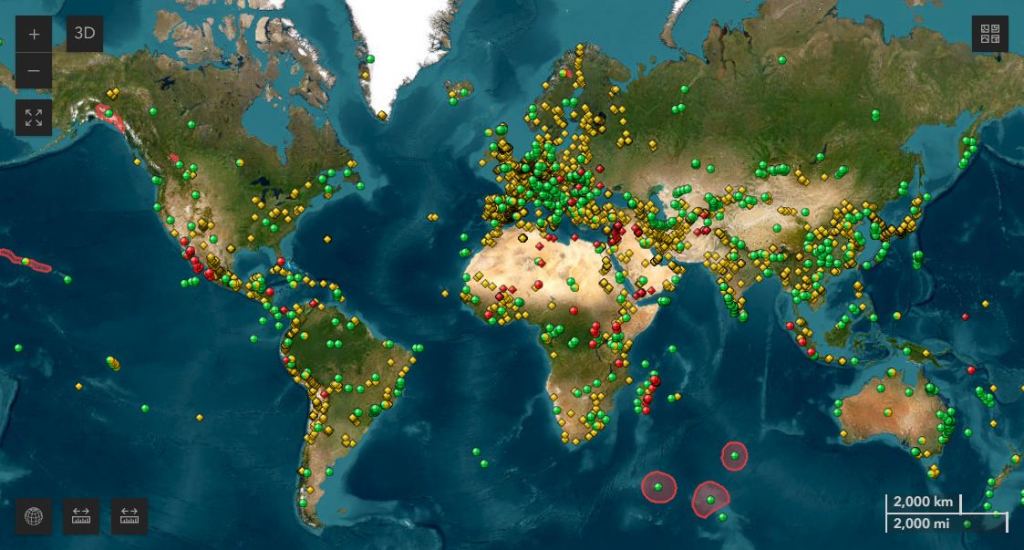

We're already partway to taking our abandoned artifacts seriously. The United Nations keeps a list of objects launched into space called the Register of Objects Launched into Outer Space. It's a way of identifying which countries are liable and responsible for objects in space (but not which private billionaires.) The Register was first implemented in 1976, and it says that about 88% of crewed spacecraft, elements of the ISS, satellites, probes, and landers launched into space are registered.

UNESCO also keeps a register of heritage sites, including archaeological and natural sites. The same could be done for Mars.

There's already one attempt to start documenting and mapping sites on Mars. The Perseverance Rover team is documenting all of the debris they encounter to make sure it can't contaminate sampling sites. There are also concerns that debris could pose a hazard to future missions.

According to one researcher, there is over 1700 kg (16,000) pounds of debris on Mars, not including working spacecraft. While much of it is just scraps being blown around by the wind and broken into smaller pieces, there are also larger pieces of debris and nine intact yet inoperative spacecraft.

So far, there have been only piecemeal attempts to document these Martian artifacts.

"Despite efforts from the USA's Perseverance team, there exists no systematic strategy for documenting, mapping and keeping track of all heritage on Mars," the authors write. "We anticipate that cultural

resource management will become a key objective during planetary exploration, including systematic surveying, mapping, documentation, and, if necessary, excavation and curation, especially as we expand

our material footprint across the Solar System."

Holcomb and his co-authors say we must understand that our spacecraft debris is the archaeological record of our attempt to explore not just Mars but the entire Solar System. Our effort to understand Mars is also part of our effort to understand our own planet and how humanity arose. "Any future accidental destruction of this record would be permanent," they point out.

The authors say there's a crucial need to preserve things like Neil Armstrong's first footsteps on the Moon, the first impact on the lunar surface by the USSR's Luna 2, and even the USSR's Venera 7 mission, the first spacecraft to land on another planet. This is our shared heritage as human beings.

"These examples are extraordinary firsts for humankind," Holcomb and his co-authors write. "As we move forward during the next era of human exploration, we hope that planetary scientists, archaeologists and geologists can work together to ensure sustainable and ethical human colonization that protects

cultural resources in tandem with future space exploration."

There are many historical examples of humans getting this type of thing wrong, particularly during European colonization of other parts of the world. Since we're still at (we hope) the beginning of our exploration of the Solar System, we have an opportunity to get it right from the start. It will take a lot of work and many discussions to determine what this preservation and future exploration can look like.

"Those discussions could begin by considering and acknowledging the emerging archaeological record on Mars," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today