In the coming years, NASA and other space agencies will send humans back to the Moon for the first time since the Apollo Era—this time to stay! To maximize line-of-sight communication with Earth, solar visibility, and access to water ice, NASA, the ESA, and China have selected the Lunar South Pole (LSP) as the location for their future lunar bases. This will necessitate the creation of permanent infrastructure on the Moon and require that astronauts have the right equipment and training to deal with conditions around the lunar south pole.

This includes lighting conditions, which present a major challenge for science operations and extravehicular activity (EVA). Around the LSP, day and night last for two weeks at a time, and the Sun never rises more than a few degrees above the horizon. This creates harsh lighting conditions very different from what the Apollo astronauts or any previous mission have experienced. To address this, the NASA Engineering and Safety Council (NESC) has recommended developing a wide variety of physical and virtual techniques that can simulate the visual experiences of Artemis astronauts.

In the past, the design of lighting and functional vision support systems has typically been relegated to the lowest level of program planning. This worked well for the Apollo missions and EVAs in Low Earth Orbit (LEO) since helmet design alone addressed all vision challenges. Things will be different for the Artemis Program since astronauts will not be able to avoid having harsh sunlight in their eyes during much of the time they spend doing EVAs. There is also the challenge of the extensive shadowing around the LSP due to its cratered and uneven nature, not to mention the extended lunar nights.

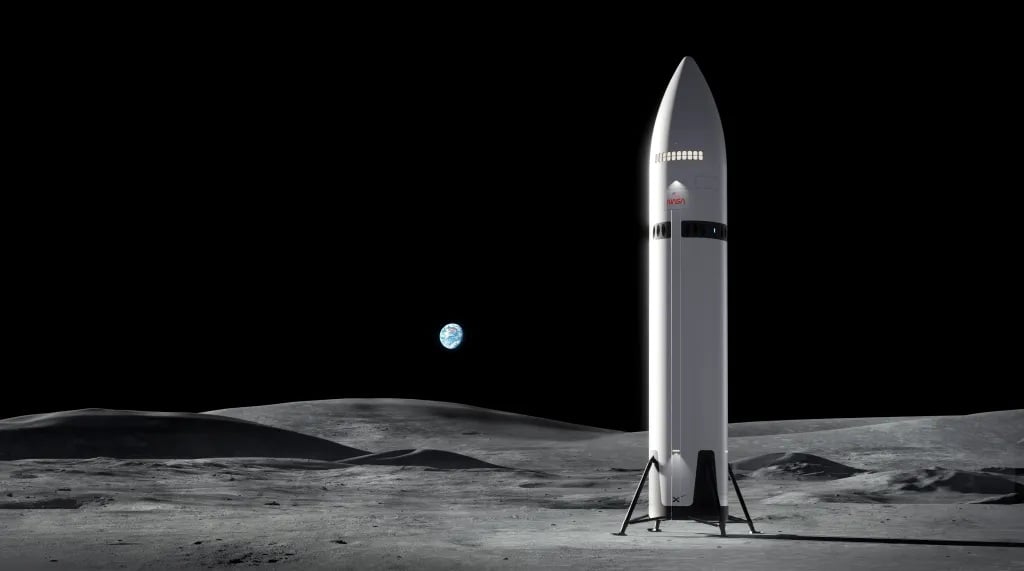

In addition, astronaut vehicles and habitats will require artificial lighting throughout missions, which means astronauts will have to transition from ambient lighting to harsh sunlight and/or intense darkness and back. Since the human eye has difficulty adapting to these transitions, it will impede an astronaut's "function vision," which is required to drive vehicles, perform EVAs safely, operate tools, and manage complex machines. This is especially true when it comes to rovers and the lander elevator used by the Starship HLS - both of which will be used for the Artemis III* and IV* missions.

As Meagan Chappell, a Knowledge Management Analyst at NASA's Langley Research Center, indicates, this will require the development of new functional vision support systems. That means helmets, windows, and lighting systems that can work together to allow crews to "see into the darkness while their eyes are light-adapted, in bright light while still dark-adapted, and protects their eyes from injury." According to the NESC assessment, these challenges have not been addressed, and must be understood before solutions can be implemented.

In particular, they indicated how functional vision and specific tasks for Artemis astronauts were not incorporated into system design requirements. For example, the new spacesuits designed for the Artemis Program - the Axiom Extravehicular Mobility Unit (AxEMU) - provide greater flexibility so astronauts can walk more easily on the lunar surface. However, there are currently no features or systems that would allow astronauts to see well enough when transitioning between brilliant sunlight into dark shadow and back again without losing their footing.

The NESC assessment identified several other gaps, prompting them to recommend that methods that enable functional vision become a specific and new requirement for system designers. They also recommended that the design process for lighting, windows, and visors become integrated. Lastly, they recommended that various physical and virtual simulation techniques be developed to address specific requirements. This means virtual reality programs that simulate what it is like to walk around the LSP during lunar day and night, followed by "dress rehearsal" missions in analog environments (or both combined!).

As Chappell summarized, the simulations will likely focus on different aspects of the mission elements to gauge the effectiveness of their designs:

"Some would address the blinding effects of sunlight at the LSP (not easily achieved through virtual approaches) to evaluate [the] performance of helmet shields and artificial lighting in the context of the environment and adaptation times. Other simulations would add terrain features to identify the threats in simple (e.g., walking, collection of samples) and complex (e.g., maintenance and operation of equipment) tasks. Since different facilities have different strengths, they also have different weaknesses. These strengths and limitations must be characterized to enable verification of technical solutions and crew training."

This latest series of recommendations reminds us that NASA is committed to achieving a regular human presence on the Moon by the end of this decade. As that day draws nearer, the need for more in-depth preparation and planning becomes apparent. By the time astronauts are making regular trips to the Moon (according to NASA, once a year after 2028), they will need the best training and equipment we can muster.

*Further Reading: NASA*

Universe Today

Universe Today