When an exoplanet is discovered, scientists are quick to describe it and explain its properties. Now, we know of thousands of them, many of which are members of a planetary system, like the well-known TRAPPIST-1 family of planets.

Patterns are starting to emerge in these exoplanetary systems, and in new research, a team of scientists says it's time to start classifying exoplanet systems rather than just individual planets.

The paper is " Architecture Classification for Extrasolar Planetary Systems, " and it's available on the pre-print site arxiv.org. The lead author is Alex Howe from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. The authors say it's time to develop and implement a classification framework for exoplanet systems based on our entire catalogue of exoplanets.

"With nearly 6000 confirmed exoplanets discovered, including more than 300 multiplanet systems with three or more planets, the current observational sample has reached the point where it is both feasible and useful to build a classification system that divides the observed population into meaningful categories," they write.

The authors explain that it's time for a systemic approach to identifying patterns in exoplanet systems. With almost 6,000 exoplanets discovered, scientists now have the data to make this proposition worthwhile.

What categories do the authors propose?

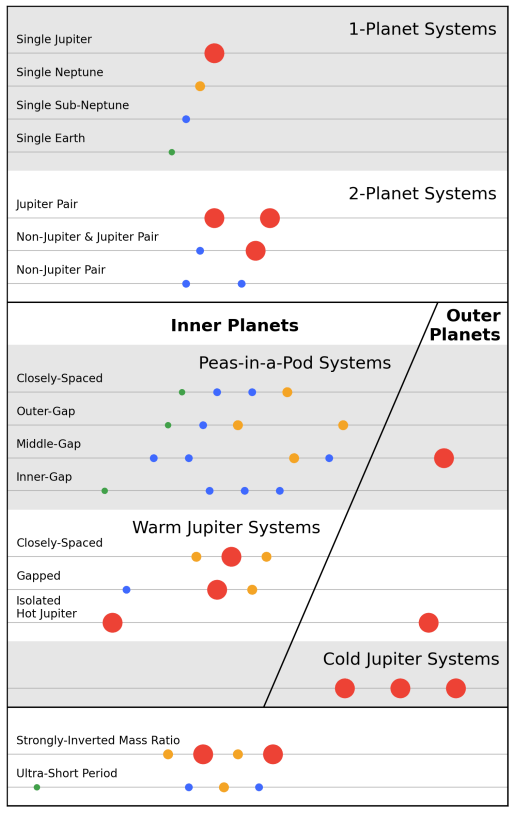

The first step is necessarily broad. "The core of our classification system comes down to three questions for any given system (although, in several cases, we add additional subcategories). Does the system have distinct inner and outer planets?" the authors write.

Next comes the question of Jupiters. "Do the inner planets include one or more Jupiters?" After that, they ask if the inner planets contain any gaps with a period ratio greater than 5. That means if within the gaps between the inner planets, are there any instances where the ratio of the orbital periods of two hypothetical planets occupying those gaps would exceed 5? Basically, that boils down to asking if the absence of planets in specific regions in the inner solar system is related to unstable orbits.

These three questions are sufficient to classify nearly all of the exoplanet systems we've discovered.

"We find that these three questions are sufficient to classify ~97% of multiplanet systems with N ?3 planets with minimal ambiguity, to which we then add useful subcategories, such as where any large gaps occur and whether or not a hot Jupiter is present," the authors write.

The result is a classification scheme that divides exoplanet systems into inner and outer regimes and then divides the inner regimes into dynamical classes. Those classes are:

- Peas-in-a-pod systems where the planets are uniformly small

- Warm Jupiter systems containing a mix of large and small planets

- Closely-space systems

- Gapped systems

There are further subdivisions based on gap locations and other features.

"This framework allows us to make a partial classification of one- and two-planet systems and a nearly complete classification of known systems with three or more planets, with a very few exceptions with unusual dynamical structures," the authors explain.

In summary, the classification scheme first divides systems into inner and outer planets (if both are detected). Systems with more than three inner planets are then classified based on whether their inner planets include any Jupiters and whether (and if so, where) their inner planets include large gaps with a period ratio >5. Some systems have other dynamical features that are addressed separately from the overall classification system.

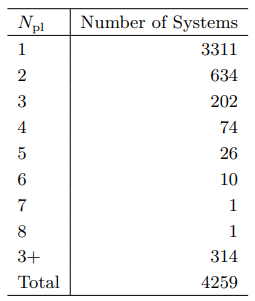

The classification system is based on NASA's Exoplanet Archive, which listed 5,759 exoplanets as of September 2024. It's a comprehensive archive, but it also contains some questionable exoplanets drawn from papers that can sometimes be inaccurate, poorly constrained, or even contradicted by subsequent papers. The researchers filtered their catalogue to remove data they considered unusable. As a result, they removed 2% of the exoplanets in their archive.

They also filtered out some of the stars because of incomplete data, which meant that planets around those stars were removed, too. Planets orbiting white dwarfs and pulsars were removed, as were planets orbiting brown dwarfs. The idea was to "represent the population of planets orbiting main sequence stars," as the authors explain.

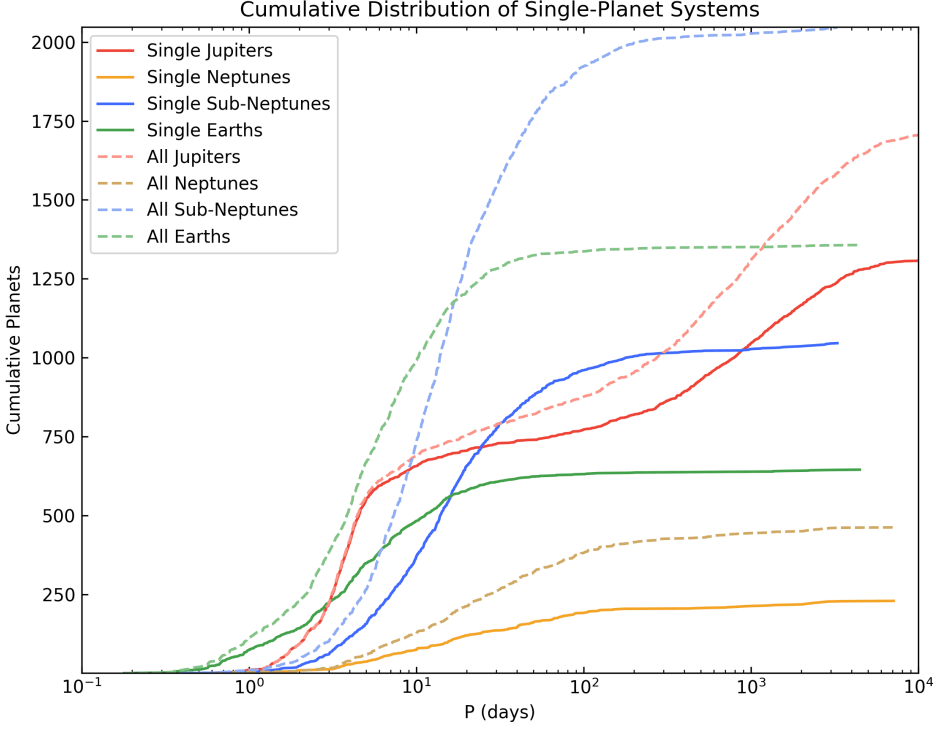

As the table above makes clear, most exoplanet systems contain only a single detected planet. 78% of them host only one planet, often a hot Jupiter, though selection effects play a role in the data. Jupiters are a key planet type in nature and in the classification scheme.

"As expected, Jupiter-sized planets are far less likely to occur in multiplanet systems at periods of <10 days and virtually none do at <5 days, as indicated by the near-coincidence of the two Jupiter distributions at those periods. Meanwhile, roughly half of all other planet types and even a third of Jupiters at periods >10 days occur in multiplanet systems," the authors explain.

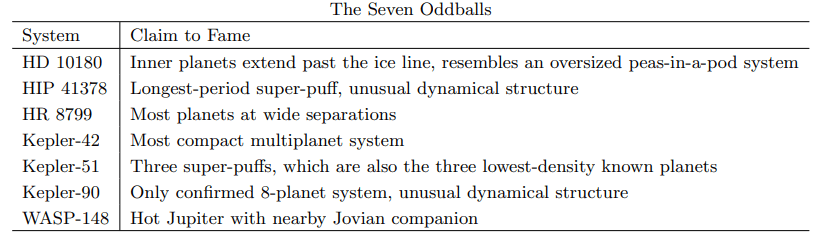

The classification system does a good job of capturing the large majority of exoplanet system architectures. However, there are some oddballs, including the WASP-148 system, the only known system with a hot Jupiter and a nearby Jupiter companion. "Given the high detection probability of such a companion and the fact that 10 hot Jupiters are known to have smaller nearby companions, this points to an especially rare subtype of system and potential unusual migration processes," the authors write.

Though exoplanet systems seem to be very diverse, this classification scheme shows that there's a lot of uniformity in the patterns. Even though there's a large diversity of planet types, most inner systems are either peas-in-a-pod systems or warm Jupiter systems. "Only a tiny minority of N ?3 systems (9 out of 314) prove difficult to classify into one of these two categories," the authors write.

Like much exoplanet science, this system is hampered by detection biases. We struggle to detect small planets like Mars with our current capabilities. There could be more of them hiding in observed exoplanet systems. There are more detection problems, too, like planets on long orbits. However, the scheme is still valuable and interesting.

"This classification scheme provides a largely qualitative description of the architectures of currently observed multiplanet systems," the authors explain. "The next step is to understand how such systems are formed, and, perhaps equally important, why other dynamically plausible systems are not present in the database."

One outcome concerns the peas-in-a-pod systems. Since they're so prevalent, scientists are keen to develop theories on their formation.

The system also has implications for habitability. The outcomes show that in peas-in-a-pod systems, the planets are often too close to main sequence stars to be habitable. Conversely, these same types of systems around M-dwarfs likely have planets in their stars' habitable zones. "This may suggest that the majority of habitable planets reside around lower-mass stars in peas-in-a-pod systems," the authors explain. That brings up the familiar problem of flaring and red dwarf habitability.

Another problem this classification scheme highlights concerns super-Earth habitability. "Most planets in peas-in-a-pod systems are super-Earths, rather than Earth-sized, and may be too large for the canonical definition of a habitable planet," the authors write.

In their conclusion, the researchers explain that exoplanet systems seem to have clear organizing principles that we can use to classify distinct types of solar systems.

"Though far from complete, we believe this classification provides a better understanding of the population as a whole, and it should be fertile ground for future studies of exoplanet demographics and formation," the researchers conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today