[/caption]

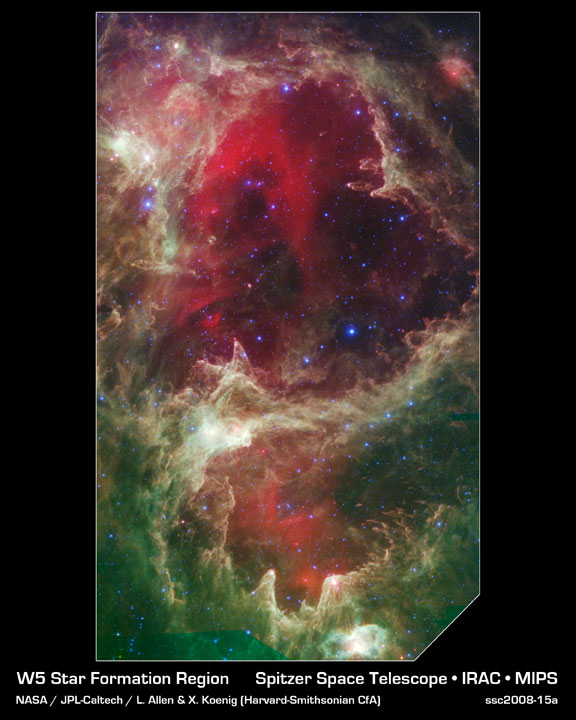

A new image from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope reveals generations of stars amid a cavity carved from a colorful cosmic cloud. The striking infrared picture shows a region, called W5, which is similar to N44F, or the “Celestial Geode” that was discussed in a Universe Today article last week. The gas cavity, which looks similar to a geode-like cavity found in some rocks, is carved by the stellar wind and intense ultraviolet radiation from hot stars. W5 is studded with stars of various ages, and provides new evidence that massive stars – through their brute winds and radiation – can trigger the birth of new stars.

The image was unveiled today at the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles as part of Spitzer’s five-year anniversary celebration. Spitzer launched on August 25, 2003, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. A high-resolution version of the image is available here. It shows a family history full of life and death. But are the deaths of some stars responsible for the birth of new stars?

“Triggered star formation continues to be very hard to prove,” said Xavier Koenig of the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. “But our preliminary analysis shows that the phenomenon can explain the multiple generations of stars seen in the W5 region.”

The most massive stars in the universe form out of thick clouds of gas and dust. The stars are so massive, ranging from 15 to about 60 times the mass of the Sun, that some of their material slides off in the form of winds. The scorching-hot stars also blaze with intense radiation. Over time, both the wind and radiation blast away surrounding cloud material, carving out expanding cavities.

Astronomers have long suspected that the carving of these cavities causes gas to compress into successive generations of new stars. As the cavities grow, it is believed that more and more stars arise along the cavities’ expanding rims. The result is a radial “family tree” of stars, with the oldest in the middle of the cavity and younger and younger stars farther out.

The astronomer who last week explained the N44F image, Dr. You-Hua Chu from the University of Illinois, said along the walls of the cavity there are dust pillars sticking out and young stars are being formed at the tips of these pillars. Similar features are seen in the new Spitzer image of W5, where younger stars (seen as pink or white in the image) are embedded in the elephant-trunk-like pillars as well, and also beyond the cavity rim. The most massive stars (seen as blue dots) are at the center of two hollow cavities.

With Spitzer’s infrared vision, Koenig and his colleagues peered through the dusty regions of W5 to get a better look at the stars’ various stages of evolution and test the triggered star formation theory. The results from their studies show that stars within the W5 cavities are older than stars at the rims, and even older than stars farther out past the rim. This ladder-like separation of ages provides some of the best evidence yet that massive stars do, in fact, give rise to younger generations.

“Our first look at this region suggests we are looking at one or two generations of stars that were triggered by the massive stars,” said co-author Lori Allen of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. “We plan to follow up with even more detailed measurements of the stars’ ages to see if there is a distinct time gap between the stars just inside and outside the rim.”

Millions of years from now, the massive stars in W5 will die in tremendous explosions. When they do, they will destroy some of the young nearby stars – the same stars they might have triggered into being.

W5 spans an area of sky equivalent to four full moons and is about 6,500 light-years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. The Spitzer picture was taken over a period of 24 hours. The color red shows heated dust that pervades the region’s cavities. Green highlights the dense clouds, and white knotty areas are where the youngest of stars are forming. The blue dots are older stars in the region, as well as other stars in the background and foreground.

A paper on the findings will appear in the December 1, 2008, issue of the Astrophysical Journal.

This image is breathtaking in its color and clarity, yet its beauty has been invisible to mankind until now. I wonder what other surprises Nature has in store for us?

For someone living on a planet orbiting one of those stars, what would the night sky look like? Would those magnificent gas clouds be visible to the naked eye (assuming they have eyes, of course)?

I think not…

First because they are inside, and second, those clouds are no as surface-bright as the image suggests.. So to see any of this, they will also have to use high-sensitive sensors, just as we have to.

The paper referenced in the above article by Nancy is arXiv:0808.3284v1 and it contains many more color pics & info on the star forming region W5. Check it out just for the cool IR pictures. It’s just been posted at the arXiv site 8-26-08.

For Steve, anyone residing inside this (or any other similar bubble) would be exposed to high levels of high energy radiation. The first stars to form would be the O & B-type supergiants, whose energetic ‘winds’ create the cavity in the gas in the first place. Even solar-mass stars & their nascent protoplanetary systems would have little time to mature in this highly energetic ‘Stromgen sphere’. Maybe life heavily shielded below planetary surfaces would have a chance to evolve & peek out at their surroundings, but again, the O & B stars have relatively short lifetimes and are prone to go supernova, perhaps before life gets a foothold on a planet orbiting a solar mass star. It’s a rough neighborhood inside these spheres, but I agree, just the view would be quite a thrill.