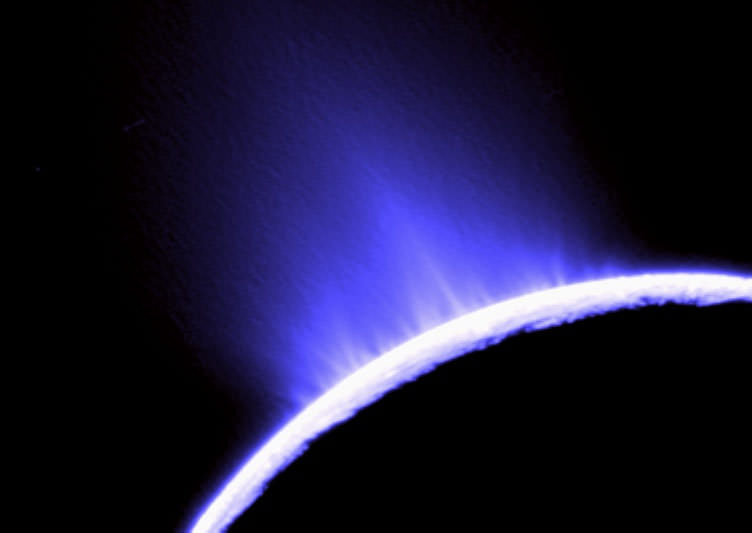

Plumes of Enceladus. Credi: NASA/JPL

[/caption]

A team of planetary scientists working on the Cassini-Huygens mission has discovered tiny, icy particles in the plume from Saturn’s moon Enceladus that offer a tantalizing glimpse of the interior of this enigmatic world. The spectrometer on Cassini, the Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS) discovered a surprise: the ice particles are electrically charged.

Cassini has been exploring Saturn and its moons since 2004. Enceladus is 500 kilometers (300 miles) wide and Cassini’s suite of instruments has found the moon to be active, with jets near its southern pole that spew gas and water thousands of kilometers out into space. During two particularly close flybys of the moon in 2008, skimming only 52 and 25 km from the surface at around 15 km per second (54,000 km per hour), the CAPS instrument on the spacecraft was pointed to scoop up gas as it zoomed through the plume.

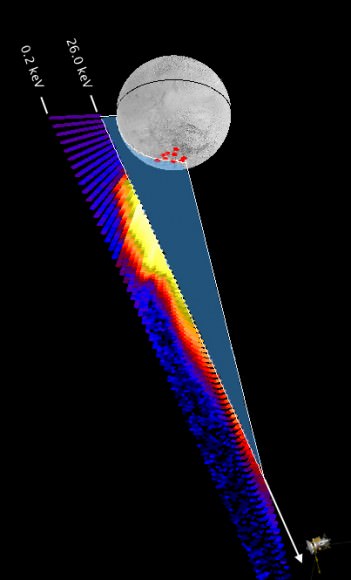

The CAPS instrument is designed to detect charged gas (plasma), but its measurements in the plume revealed tiny ice grains whose signatures could only be present if they were electrically charged. These grains, probably only measuring a few nanometres across (billionths of a meter – 50, 000 times thinner than a human hair), fall into a size range between gas atoms and much larger ice grains, both of which were sampled directly during previous Enceladus flybys. The particles have both positive and negative electrical charges, and the mix of the charges varied as the Cassini spacecraft crossed the plume.

Dr. Geraint Jones and Dr. Chris Arridge, both from University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, present the results for the CAPS team at the European Week of Astronomy and Space Science conference at the University of Hertfordshire.

Jones and Arridge suggest that the grains may be charged through so-called triboelectric processes, through bumping together in the vent below Enceladus’s surface before they emerge into the plume. This provides important hints to the conditions in the vents, and in turn may help with understanding conditions in the interior.

Jones and Arridge are intrigued by what their discovery reveals about Enceladus: “What are particularly fascinating are the bursts of dust that CAPS detects when Cassini passes through the individual jets in the plume” says Jones. “Each jet is split according to charge though”, adds Arridge, “Negative grains are on one side, and positive ones on the other”.

Arridge said that perhaps, as these charged grains travel away from Enceladus, their paths are bent by electric and magnetic fields in Saturn’s giant magnetosphere. In this way Saturn’s magnetosphere acts as an enormous mass spectrometer for the plume particles, allowing scientists to constrain their masses. Arridge has begun modelling the paths of these newly-discovered particles.

Ionised gas (plasma) in Saturn’s magnetosphere flows past Enceladus at over 80000 km per hour. Arridge’s results show that for this enormous mass spectrometer to work and for these dust particles to reach Cassini, this river of plasma must be significantly slowed down, in and near the plume, to speeds of less than 3200 km per hour. This slowing of the plasma is a result of the plume injecting particles into the plasma stream – making the whole flow slow down in a similar effect to when cars join a busy motorway. These new results provide further evidence that the material in the Enceladus plume has a huge influence on the moon’s surroundings.

Future Cassini flybys will help further understand the processes that occur at Enceladus and in its vicinity. William Herschel could not have suspected that the tiny point of light that he found in 1789 would turn out to be such an exotic place.

Source: RAS

Every Martian year (which last 686.98 Earth days), the Red Planet experiences regional dust storms…

If Intermediate-Mass Black Holes (IMBHs) are real, astronomers expect to find them in dwarf galaxies…

There are plenty of types of stars out there, but one stands out for being…

As far as we can tell, life needs water. Cells can't perform their functions without…

Dubbed CADRE, a trio of lunar rovers are set to demonstrate an autonomous exploration capability…

Astronomers have identified sulfur as a potentially crucial indicator in narrowing the search for life…