Welcome to another installment of Messier Monday! Today, we continue in our tribute to our dear friend, Tammy Plotner, by taking a look at Messier Object 10.

In the 18th century, French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky while searching for comets. Hoping to ensure that other astronomers did not make the same mistake, he began compiling a list of 1oo of them. This list came to be known as the Messier Catalog, and would have far-reaching consequences.

In addition to being as a major milestone in the history of astronomy and the study of Deep Sky Objects. One of these objects is known as Messier 10 (aka. NGC 6254), a globular cluster that is located in the equatorial constellation of Ophiuchus. Of the many globular clusters that appear in this constellation (seven of which were cataloged by Messier himself) M10 is the brightest, and can be spotted with little more than a pair of binoculars.

Description:

The M10 cluster is one of the closer objects to the center of our galaxy, located just 5 kiloparsecs (16,000 light years) from the Galactic Center, and about 14,000 light years from Earth. Measuring some 83 light-years in diameter, this cluster has diffuse edges that reach beyond its much-brighter core, which measures roughly 35 light-years across. On average, the cluster is very bright, with a visual magnitude of 6.6.

The core region is home to many binary stars, which tend to migrate towards the core due to their greater mass. Binary stars are estimated to make of 14% of the core region of the cluster, while making up just 1.5% of the outlying regions. Similarly, the core region contains a concentration of interaction-formed blue straggler stars – a type of main sequence star common to clusters that are particularly bright – as well as four variable stars.

In terms of the abundance of elements other than hydrogen and helium, Messier 10 is moderately metal–poor. The abundance of iron, is only 3.5% of the abundance found at the surface of the Sun. In addition, it also appears in close proximity to another object in Ophiuchus, the globular cluster M12. Although they seem to be close together and close in size, the M10/M12 pair are actually separated by some 2,000 light-years.

M10 is a also a much more concentrated globular showing a brighter core region to even the most modest of instruments. This compression of stars is what classifies one type of globular cluster from another, and M10 appears brighter, not because of this compression, but because it is about 2,000 light-years closer.

Traveling away from us at 69 kilometers per second, 532 stars have been measured for their absolute proper motions, and we know that two of them are population II cepheids. Why is knowing proper motion so important? So we can study the evolution. According to studies done on M10 by Oleg Y. Gnedin (et al):

“As an example, we investigate the evolution of models for the globular cluster NGC 6254. Using the Hipparcos proper motions, we are now able to construct orbits of this cluster in the Galaxy. Tidal shocks accelerate significantly both core collapse and the evaporation of the cluster and shorten the destruction time from 24 to 18 Gyr. We examine various types of adiabatic corrections and find that they are critical for accurate calculation of the evolution. Without adiabatic corrections, the destruction time of the cluster is twice as short. We examine cluster evolution for a wide range of the concentration and tidal shock parameters and determine the region of the parameter space where tidal shocks dominate the evolution. We present fitting formulae for the core collapse time and the destruction time, covering all reasonable initial conditions. In the limit of strong shocks, the typical value of the core collapse time decreases from 10trh to 3trh or less, while the destruction time is just twice that number. The effects of tidal shocks are rapidly self-limiting: as clusters lose mass and become more compact, the importance of the shocks diminishes. This implies that tidal shocks were more important in the past.”

History Of Observation:

M10 was discovered by Charles Messier on May 29, 1764. Said he:

“In the night of May 29 to 30, 1764, I have determined the position of a nebula which I have discovered in the girdle of Ophiuchus, near the 30th star of that constellation, of sixth magnitude. according to the catalog of Flamsteed. When having examined that nebula with a Gregorian telescope of 30 pouces which magnified 104 times, I have not seen any star there: it is round and beautiful, its diameter is about 4 minutes of arc; one sees it difficultly with an ordinary [non-achromatic] refractor of one foot [FL]. Near that nebula one perceives a small telescopic star. I have determined the right ascension of that nebula as 251d 12′ 6″, and its declination as 3d 42′ 18″ south. I marked that nebula in the chart of the apparent path of the Comet which I have observed last year [the comet of 1769].”

Although William Herschel would be the first to resolve it into stars, it is the words of Admiral Symth which most accurately reflect how M10 truly looks in the average telescope:

“A rich globular cluster of compressed stars, on the Serpent-holder’s right hip. This noble phenomenon is of a lucid white tint, somewhat attenuated at the margin, and clustering to a blaze in the centre. It is so easily resolvable with very moderate means, that we are surprised at Messier’s remark, on registering it in 1764: ‘A beautiful round nebula. It may be seen, with attention, by a telescope of three feet in length.’ The mean apparent place of the central mass, was differentiated with Epsilon Ophiuchi, which it follows nearly on the same eastern parallel, at about 8 deg distance; being nearly midway between Beta Librae and Alpha Aquilae, and about a degree preceding [west of] 30 Ophiuchi, a star of the 6th magnitude, with a smaller one preceding it. Sir William Herschel resolved this object; in 1784 he applied his 20-foot reflector, and made it a beautiful cluster of extremely compressed stars, resembling Messier’s No. 53. He estimated its profundity to be of the 243rd order.”

Locating Messier 10:

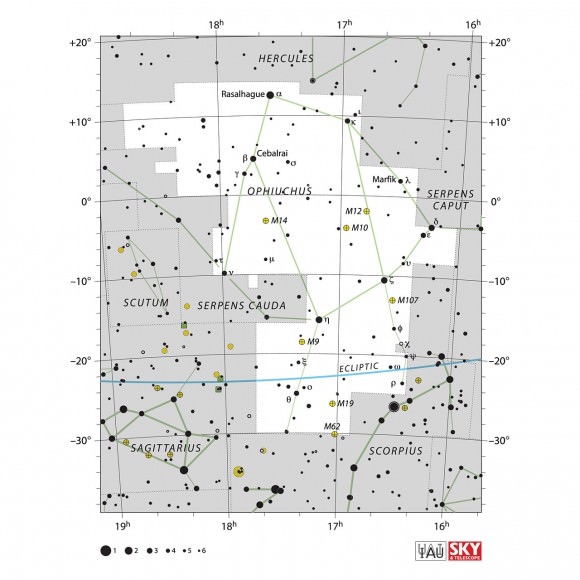

Using binoculars, M10 is a same-field binocular pair with globular cluster M12, which is located about half the width of a fist west of Beta Ophiuchi. M10 is the southernmost of this pair and will appear brighter in the night sky. To help orient yourself to the correct area, identify Beta Scorpii as your first starhop marker. Slightly more than a fist-width north, you will see the twin “Yed” stars (Delta and Epsilon, traditionally known as Yed Prior and Yed Posterior).

To the northeast are another close, bright pairing – Beta and Gamma Ophiuchi. M10 and M12 are about 1/3 the distance between the twin Yeds and the Beta/Gamma pair. Both are bright enough to be seen as a small, fuzzy patch in the finderscope.

And for your convenience, here are the quick facts about Messier 10:

Object Name: Messier 10

Alternative Designations: M10, NGC 6254

Object Type: Class VII Globular Cluster

Constellation: Ophiuchus

Right Ascension: 16 : 57.1 (h:m)

Declination: -04 : 06 (deg:m)

Distance: 14.3 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 6.6 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 20.0 (arc min)

Whether you resolve it or not – the beauty is finding it!

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Thank You on this fascinating series. As I find more targets for my telescope, my mind wanders to what those early astronomers were thinking about when they seen some of these stars for the first time.

I use to dream of becoming an Astronomer but didn’t.

Fascinating no matter how you look at it. As a child, the night sky appeared awesome to me. Still does.