[/caption]

Researchers have breathed new life into a bacterium trapped deep under glacial ice in Greenland — for over 120,000 years.

The researchers, who hail from Pennsylvania State University, say the newly discovered bacterium may hold clues as to what life forms might be frozen on other planets.

Jennifer Loveland-Curtze and her team of scientists at Penn State report finding the novel microbe, which they have called Herminiimonas glaciei, in the current issue of the International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology.

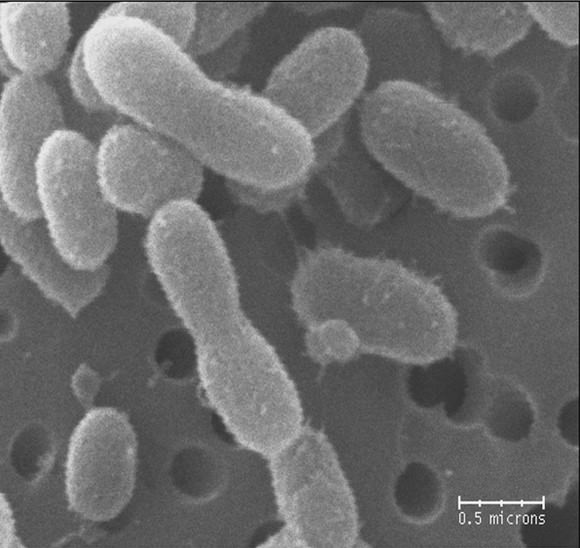

From samples recovered nearly two miles (more than 3 kilometers) in a Greenland glacier, the team coaxed the dormant microbe back to life, first incubating their samples at 2 degrees C (35 degrees F) for seven months and then at 5 degrees C (41 degrees F) for four and a half months more, after which colonies of very small purple-brown bacteria were seen.

H. glaciei is small even by bacterial standards – it is 10 to 50 times smaller than E. coli. Its small size probably helped it to survive in the liquid veins among ice crystals and the thin liquid film on their surfaces. Small cell size is considered to be advantageous for more efficient nutrient uptake, protection against predators and occupation of micro-niches and it has been shown that ultramicrobacteria are dominant in many soil and marine environments.

Most life on our planet has always consisted of microorganisms, so it is reasonable to consider that this might be true on other planets as well. Studying microorganisms living under extreme conditions on Earth may provide insight into what sorts of life forms could survive elsewhere in the solar system.

“These extremely cold environments are the best analogues of possible extraterrestrial habitats,” Loveland-Curtze said. “The exceptionally low temperatures can preserve cells and nucleic acids for even millions of years. H. glaciei is one of just a handful of officially described ultra-small species and the only one so far from the Greenland ice sheet; studying these bacteria can provide insights into how cells can survive and even grow under extremely harsh conditions, such as temperatures down to -56 degrees C (-68 degrees F), little oxygen, low nutrients, high pressure and limited space.”

The tiny bacteria also provide a warning about more common bacteria on Earth, Loveland-Curtze pointed out.

“H. glaciei isn’t a pathogen and is not harmful to humans,” she said, “but it can pass through a 0.2 micron filter, which is the filter pore size commonly used in sterilization of fluids in laboratories and hospitals. If there are other ultra-small bacteria that are pathogens, then they could be present in solutions presumed to be sterile.”

Source: Eurekalert

50 times maller than E Coli.

The possible fossil structures in ALH84001 are about 200 times (if memory serves) smaller than standard bacteria.

A possible missing link in terms of size.