[/caption]

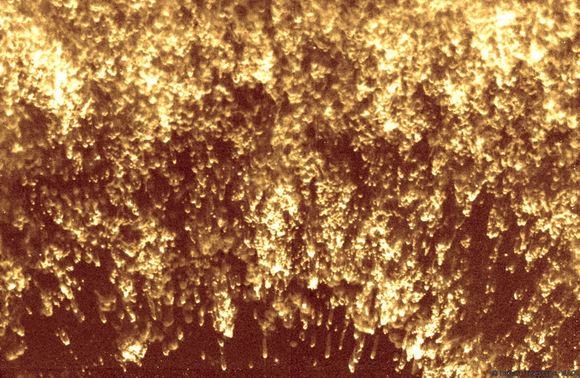

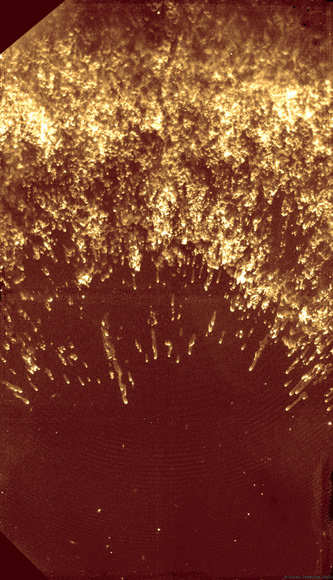

Astronomers working with the Subaru Telescope have released these new images of a “fireworks display” in a near-infrared image of the Helix Nebula, showing comet-shaped knots within.

The Helix Nebula, NGC 7293, is not only one of the most interesting and beautiful planetary nebulae; it is also one of the closest nebulae to Earth, at a distance of only 710 light years away. The new image, taken with an infrared camera on the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, shows tens of thousands of previously unseen comet-shaped knots inside the nebula. The sheer number of knots–more than have ever been seen before—looks like a massive fireworks display in space.

The Helix Nebula was the first planetary nebula in which knots were seen, and their presence may provide clues to what planetary material may survive at the end of a star’s life. Planetary nebulae are the final stages in the lives of low-mass stars, such as our Sun. As they reach the ends of their lives they throw off large amounts of material into space. Although the nebula looks like a fireworks display, the process of developing a nebula is neither explosive nor instantaneous; it takes place slowly, over a period of about 10,000 to 1,000,000 years. This gradual process creates these nebulae by exposing their inner cores, where nuclear burning once took place and from which bright ultraviolet radiation illuminates the ejected material.

![Previous optical image of the Helix Nebula, demonstrating diffuse gas surrounding a central star. The white box shows the area observed by the Subaru Telescope. Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner [STScI], and T.A. Rector [NRAO] Previous optical image of the Helix Nebula, demonstrating diffuse gas surrounding a central star. The white box shows the area observed by the Subaru Telescope. Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner [STScI], and T.A. Rector [NRAO]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/afig4.jpg)

Astronomers from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ), from London, Manchester and Kent universities in the UK and from the University of Missouri in the US studied the emissions from hydrogen molecules in the infrared and found that knots are found throughout the entire nebula. Although these molecules are often destroyed by ultraviolet radiation in space, they have survived in these knots, shielded by dust and gas that can be seen in optical images. The comet-like shape of these knots results from the steady evaporation of gas from the knots, produced by the strong winds and ultraviolet radiation from the dying star in the center of the nebula.

Unlike previous optical images of the Helix Nebula knots, the infrared image shows thousands of clearly resolved knots, extending out from the central star at greater distances than previously observed. The extent of the cometary tails varies with the distance from the central star, just as Solar System comets have larger tails when they are closer to the Sun and when wind and radiation are stronger. “This research shows how the central star slowly destroys the knots and highlights the places where molecular and atomic material can be found in space,”says lead astronomer Dr. Mikako Matsuura, previously at NAOJ and now from University College London.

These images enable astronomers to estimate that there may be as many as 40,000 knots in the entire nebula, each of which are billions of kilometers/miles across. Their total mass may be as much as 30,000 Earths, or one-tenth the mass of our Sun. The origin of the knots is currently unknown.

This paper will be published in the Astrophysical Journal in August 2009

Final image caption: Previous optical image of the Helix Nebula, demonstrating diffuse gas surrounding a central star. The white box shows the area observed by the Subaru Telescope. Credit: NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner [STScI], and T.A. Rector [NRAO]

Source: NAO of Japan

Nice work.

I’m curious though, what exactly is a knot? A clump of hydrogen shielded by dust etc ? Since these knots are slowly destroyed, or pushed away, by stellar wind, can their density and/or distance from the star be any indicator of the age of the nebula?

A preprint of the paper with MANY color and B&W images can be found here: http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0906/0906.2870v1.pdf . There are some pretty cool comparison pix with previous HST observations of these knots in different wavelengths.

@Kaizad, from the paper cited above and other sources, it appears that the knots are composed of clumps of molecular gas clouds and dust, some apparently quite dense. Researchers are still unsure of when these knots were formed and exactly how to interpret various features seen in them ( i.e. the reason for their cometary or ‘head-tail’ appearance). The paper I linked to has many wonderful images of specific knots in various wavelengths and several interpretations of their appearance. The authors relate that their observations will probably not answer the question of the knots’ origin but may be useful in developing a cohesive model of the evolution and fate of the knots, so I would guess that information on the age of the Helix might also be deduced from their observations. Hope some of this has made sense 🙂 . Btw, the short paper has many references to earlier work on the origin, age and evolution of the knots.

Thanks for the link Jon, I went through it when you posted it.