[/caption]

NASA researchers have published confirmation this week that the Kepler mission will be able to reveal the presence of Earth-sized planets around Sun-like stars. The mission’s first scientific results appear today in the journal Science.

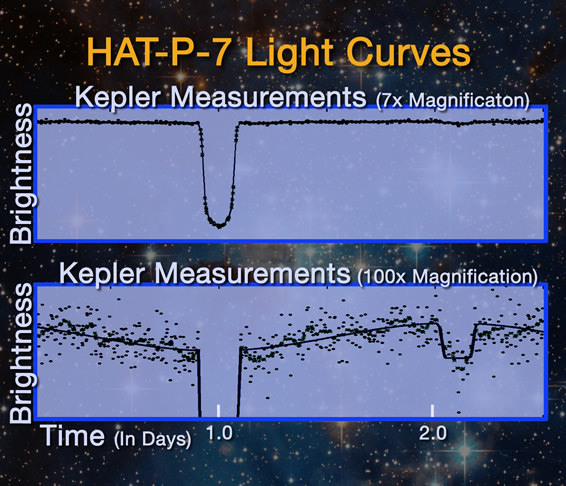

Lead author William Borucki, of NASA Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, and his colleagues announced that Kepler has detected the giant extrasolar planet HAT-P-7b, one of the roughly two dozen exoplanets that have been discovered by ground-based observations and the CoRoT mission as they “transited” in front of their stars, periodically dimming the starlight.

Many more exoplanets — more than 300 now — have been detected by the so-called “wobble” or radial velocity method, where a planet’s gravitational tug influences the motion of its star.

HAT-P-7b is comparable to Jupiter in size and orbits a star analogous to our Sun. It showed up in 10 days’ worth of Kepler data on the intensity of light from over 50,000 stars.

“The detection of the occultation without systematic error correction demonstrates that Kepler is operating at the level required to detect Earth-size planets,” the authors write.

The $500 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009 and will spend three and a half years surveying more than 100,000 sun-like stars in Cygnus-Lyra.

By staring at one large patch of sky for the duration of its lifetime, Kepler will be able to watch planets periodically transit their stars over multiple cycles, allowing astronomers to confirm the presence of planets and use the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes, along with ground-based telescopes, to characterize their atmospheres and orbits. Earth-size planets in habitable zones would theoretically take about a year to complete one orbit, so Kepler will monitor those stars for at least three years to confirm the planets‘ presence.

Astronomers estimate that if even one percent of stars host Earth-like planets, there would be a million Earths in the Milky Way alone. If that’s true, hundreds of Earths should exist in Kepler’s target population of 100,000 stars.

Source: Science and NASA’s Kepler page

An interesting and exciting article, thanks Anne! I eagerly await the discovery of the first earth size exoplanet. One concern, however…how accurate are the estimates of one percent of stars hosting earth-like planets considering none have been discovered using conventional transiting and radial velocity discovery methods. Just wondering…

Isn’t the title of the article a bit misleading? HAT-P-7b is not a new discovery, but the title makes it sound like it is.

It’s the fact that it found the planet we already knew about with a mere ten days of data which is the real story. The mission hadn’t even begun yet – this data was from when they were calibrating Kepler.

Once Kepler starts discovering Earth sized planets, surely this would be useful for tweaking the Drake equation? Knowing what minimum percentage of earth sized planets are orbiting around 50,000 odd stars, would this be of any statistical significance?

Can the stars in Cygnus-Lyra be considered ‘normal’ enough to extrapolate across the Milky Way’s star population to estimate the number of earth sized planets in our galaxy?

“Can the stars in Cygnus-Lyra be considered ‘normal’ enough to extrapolate across the Milky Way’s star population to estimate the number of earth sized planets in our galaxy?”

Not necessarily I guess, but something is better than nothing. At least it’ll provide some constraints!

This is a little misleading. There may be hundreds of Earths orbiting Kepler’s target stars, but only a small percentage of them will ever pass between their star and (our) Earth and cause a transit.

The stated mission target is to detect 50 Earth-like planets.

Overall, of course, they hope to find well over 1,000, but the majority will be gas giants like HAT-P-7b.

Still, it’s great to have confirmation that Kepler is working as design. It’s just a bit of a bummer that we will have to wait until next year for the first new detections to be announced…

Good point, Jesper. Changed!

Great. I’m glad it works. This is my favourite mission in Astronomy.

As I understand it from press releases and other articles, it is comparing the small dip in brightness from the planet being occulted by the star with the large dip that is of interest. [But no one was interested enough to publish the measurements. Thanks Anne!]

As they say, the brightness differential from the reflected star light is ~ 1 % of the usual main star transit of the planet.

And Kepler can marginally see that, which apparently is needed for the Earth analog detections. So: yay! (I’ll say that again: yay!)

I’m not sure what you mean with this.

Obviously few terrestrial planets (ie planets mainly massing from rocks) have been found inside the habitable zone, as Kepler is AFAIU the first instrument capable of and dedicated to observing such down to Earth size and out to Earth orbit for a large enough population to score results “soon”. (Sigh, still 3 years to go.)

[Actually, if the follow up mission goes through I believe it will be out to Mars orbit. And possibly they can shave off some of the surface area restraints as well by observing more transits.]

But terrestrial planets have been found, most still with substantial higher mass, say an order of magnitude.

Which nevertheless translates to the same order of radius and surface gravity, even higher possibility for plate tectonics, et cetera. One of them is IIRC marginally within the habitable zone if you account for an atmosphere. And one is less than twice Earth mass. How Earth like is “earth-like”?

IIRC and AFAIU astronomers conclude that trends point to rocky planets being numerous, more so than gas giants, after you account for the sensitivity of the methods used. Ie our own system looks rather ordinary.

This estimate is independent of the estimate given, which was just an estimate of the size of the population Kepler will study based on a base figure. But it will raise that figure one or two orders of magnitude.

OTOH the transit methods will only catch a few percent of those which happens to coincide with our own orbit position (as tacitus point out). Calculating from the assumed catch of ~ 50 “Earth-like” planets, Kepler will study a population having, say, a mere ~ 2000 “Earth-likes”, from nearly 2 % of the stars.

I guess “Earth-likes” aren’t simply terrestrial planets then. It’s a much more restricted set, likely of roughly the same mass.

You stated…

Astronomers estimate that if even one percent of stars host Earth-like planets, there would be a million Earths in the Milky Way alone.

Maybe my math is wrong but…

If the Milky Way contains 200 billion stars, one percent of 200 billion would be 2 billion with earth-like planets, not a million stars.

@Torbjorn Larsson, I guess I should have specified earth-size, rather than earth like. It is encouraging that an explanet has been discovered at 1.9 earth masses, and I eagerly await the discovery of terrestial planets more closely aligned with the specific characteristics of earth….maybe I’m a dreamer. But, finding in excess of 350 explanets in roughly 18 years portends great discoveries to come, IMHO. @TexasStargazer, looks like your math computes.

GekkoNZ, that’s a blasphemy. Who cares about Drake equation? It’s just a marketing tool.

Great story and discussion, Annne, on Kepler’s mission and objectives. Many thanks for posting the HAT-7-b light curves, so we can all see the tales that Kepler can tell us. As for the Kepler mission overall, observations have just begun (in a big way), so let’s not prejudge Kepler in its scientific infancy 🙂