Chances are that if you have lived on this planet for the past half-century, you've heard of NASA. As the agency that is in charge of America's space program, they put a man on the Moon, launched the Hubble Telescope, helped establish the International Space Station, and sent dozens of probes and shuttles into space.

But do you know what the acronym NASA actually stands for? Well, NASA stands for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. As such, it oversees America's spaceflight capabilities and conducts valuable research in space. NASA also has various programs on Earth dedicated to flight, hence why the term "Aeronautics" appears in the agency's name.

However, the real meaning behind this famous acronym cannot be understood until without learning about the history of the organization. Born during the height of the Cold War, NASA was founded for the straightforward purpose of ensuring American dominance in space. But in the many generations since its inception, NASA's mission has evolved considerably.

Formation

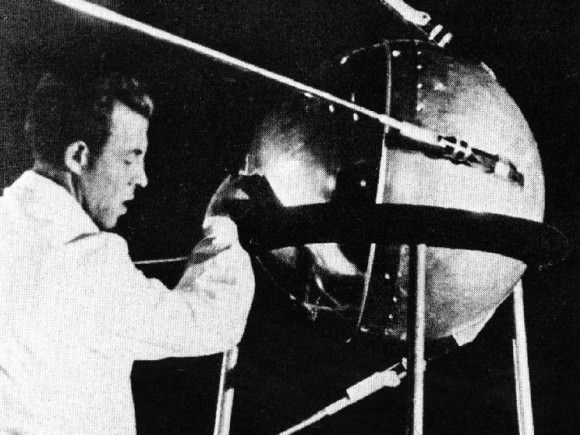

The process of forming NASA began in the early 1950s with the development of rocket planes - like the Bell X-1 - and the desire to launch physical satellites. However, it was not until the launch of Sputnik 1 - the first artificial satellite into space that was deployed by the Soviets on October 4th, 1957 - that efforts to develop an American space program truly began.

Fearing that Sputnik represented a threat to national security and America's technological leadership, Congress urged then-President Dwight D. Eisenhower to take immediate action. This result in an agreement whereby a federal organization similar to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) - which was established in 1915 to oversee aeronautical research - would be created.

On July 29th, 1958, Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act, which officially established NASA. When it began operations on October 1st, 1958, NASA absorbed NACA and its 8,000 employees. It was also given an annual budget of US $100 million, three major research laboratories (Langley Aeronautical Laboratory, Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, and Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory) and two small test facilities.

Elements of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and the United States Naval Research Laboratory were also incorporated into NASA. A significant contribution came from the work of the Army Ballistic Missie Agency (ABMA), which had been working closely with Wernher von Braun - the leader of Germany's rocket program during WWII - at the time.

In December 1958, NASA also gained control of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a contractor facility operated by the California Institute of Technology. By 1959, President Eisenhower officially approved of A NASA seal, which is affectionately referred to as the "meatball" logo because of the orbs included in the design.

Early Projects

NASA has since been responsible for the majority of the manned and unmanned American missions that have been sent into space. Their efforts began with the development of the X-15, a hypersonic jet plane that NASA had taken over from the NACA. As part of the program, twelve pilots were selected to fly the X-15, and achieve new records for both speed and maximum altitude reached.

A total of 199 flights were made between 1959 and 1968, resulting in two official world records being made. The first was for the highest speed ever reached by a manned craft - Mach 6.72 or 7,273 km/h (4,519 mph) - while the second was for the highest altitude ever achieved, at 107.96 km (354,200 feet).

The X-15 program also employed mechanical techniques used in the later manned spaceflight programs, including reaction control system jets, space suits, horizon definition for navigation, and crucial reentry and landing data. However, by the early 60's, NASA's primary concern was winning the newly-declared "Space Race" with the Soviets by putting a man into orbit.

Project Mercury

This began with the Project Mercury, a program that was taken over from the US Air Force and which ran from 1959 until 1963. Designed to send a man into space using existing rockets, the program quickly adopted the concept of launching ballistic capsules into orbit. The first seven astronauts, nicknamed the " Mercury Seven ", were selected from the Navy, Air Force, and Marine test pilot programs.

On May 5th, 1961, astronaut Alan Shepard became the first American in space aboard the Freedom 7 mission. John Glenn became the first American to be launched into orbit by an Atlas launch vehicle on February 20th, 1962, as part of Friendship 7*. Glenn completed three orbits, and three more orbital flights were made, culminating in L. Gordon Cooper's 22-orbit flight aboard Faith 7*, which flew on May 15th and 16th, 1963.

Project Gemini

Project Gemini, which began in 1961 and ran until 1966, aimed at developing support for Project Apollo (which also began in 1961). This involved the development of long-duration space missions, extravehicular activity (EVA), rendezvous and docking procedures, and precision Earth landing. By 1962, the program got moving with the development of a series of two-man spacecraft.

The first flight, Gemini 3, went up on March 23rd, 1965 and was flown by Gus Grissom and John Young. Nine missions followed in 1965 and 1966, with spaceflights lasting for nearly fourteen days while crews conducting docking and rendezvous operations, EVAs, and gathered medical data on the effects of weightlessness on humans.

Project Apollo

And then there was the Project Apollo, which began in 1961 and ran until 1972. Due to the Soviets maintaining a lead in the space race up until this point, President John F. Kennedy asked Congress on May 25th, 1961 to commit the federal government to a program to land a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s. With a price tag of $20 billion (or an estimated $205 billion in present-day US dollars), it was the most expensive space program in history.

The program relied on the use of Saturn rockets as launch vehicles, and spacecraft that were larger than either the Mercury or Gemini capsules - consisting of a command and service module (CSM) and a lunar landing module (LM). The program got off to a rocky start when, on January 27th, 1967, the *Apollo 1 c* raft experienced an electrical fire during a test run. The fire destroyed the capsule and killed the crew of three, consisting of Virgil I. "Gus" Grissom, Edward H. White II, Roger B. Chaffee.

The second manned mission, Apollo 8, brought astronauts for the first time in a flight around the Moon in December of 1968. On the next two missions, docking maneuvers that were needed for the Moon landing were practiced. And finally, the long-awaited Moon landing was made with the *Apollo 11* mission on July 20th, 1969. Astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first men to walk on the Moon while pilot Michael Collins observed.

Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. Throughout these six Apollo spaceflights, a total of twelve men walked on the Moon. These missions also returned a wealth of scientific data, not to mention 381.7 kilograms (842 lb) of lunar samples to Earth. The Moon landing marked the end of the space race, but Armstrong declared it a victory for "mankind" rather than just the US.

Skylab and the Space Shuttle Program

After Project Apollo, NASA's efforts turned towards the creation of an orbiting space station and the creation of reusable spacecraft. In the case of the former, this took the form of Skylab, America's first and only independently-built space station. Conceived of in 1965, the station was constructed on Earth and launched on May 14th, 1973 atop the first two stages of a Saturn V rocket.

Skylab was damaged during its launch, losing its thermal protection and one electricity-generating solar panels. This necessitated the first crew to rendezvous with the station to conduct repairs. Two more crews followed, and the station was occupied for a total of 171 days during its history of service. This ended in 1979 with the downing of the station over the Indian Ocean and parts of southern Australia.

By the early 70s, a changing budget environment forced NASA to begin researching reusable spacecraft, which resulted in the Space Shuttle Program. Unlike previous programs, which involved small space capsules being launched on top of multistage rockets, this program centered on the use of vehicles that were launchable and (mostly) reusable.

Its major components were a spaceplane orbiter with an external fuel tank and two solid-fuel launch rockets at its side. The external tank, which was bigger than the spacecraft itself, was the only major component that was not reused. Six orbiters were constructed in total, named Space Shuttle Atlantis, Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, Endeavour and E* nterprise*.

Over the course of 135 missions, which ran from 1983 to 1998, the Space Shuttles performed many important tasks. These included carrying the Spacelab into orbit - a joint effort with the European Space Agency (ESA) - running supplies to Mir and the ISS (see below), and the launch and successful repair of the Hubble Space Telescope (which took place in 1990 and 1993, respectively).

The Shuttle program suffered two disasters during the course of its 15 years of service. The first was the Challenger disaster in 1986, while the second - the Columbia disaster - took place in 2003. Fourteen astronauts were lost, as well as the two shuttles. By 2011, the program was discontinued, the last mission ending on July 21st, 2011 with the landing of Space Shuttle Atlantis at the Kennedy Space Center.

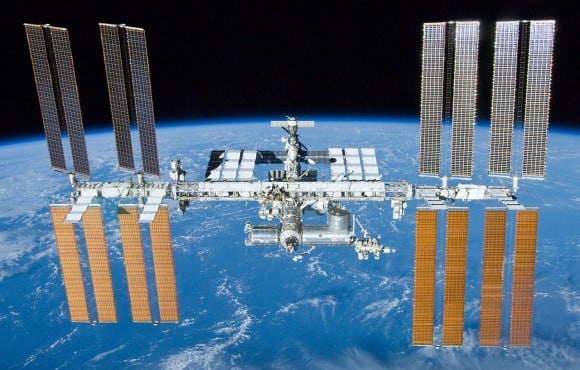

By 1993, NASA began collaborating with the Russians, the ESA and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to create the International Space Station (ISS). Combining NASA's Space Station Freedom* project with the Soviet/Russian Mir-2 station, the European Columbus* station, and the Japanese Kibo laboratory module, the project also built on the Russian-American Shuttle-Mir missions (1995-1998).

The ISS and Recent Projects

With the retirement of the Space Shuttle Program in 2011, crew members were delivered exclusively by Soyuz spacecraft. The Soyuz remains docked with the station while crews perform their six-month long missions, and then returns them to Earth. Until another US manned spacecraft is ready - which is NASA is busy developing - crew members will travel to and from the ISS exclusively aboard the Soyuz.

Uncrewed cargo missions arrive regularly with the station, usually in the form of the Russian Progress spacecraft, but also from the ESA's Automated Transfer Vehicle (ATV) since 2008, the Japanese H-II Transfer Vehicle (HTV) since 2009, SpaceX's Dragon spacecraft since 2012, and the American Cygnus spacecraft since 2013.

The ISS has been continuously occupied for the past 15 years, having exceeded the previous record held by Mir; and has been visited by astronauts and cosmonauts from 15 different nations. The ISS program is expected to continue until at least 2020, but may be extended until 2028 or possibly longer, depending on the budget environment.

Future of NASA

A few years ago, NASA celebrated its fiftieth anniversary. Originally designed to ensure American supremacy in space, it has since adapted to changing conditions and political climates. Its accomplishments have also been extensive, ranging from launching the first American artificial satellites into space for scientific and communications purposes to sending probes to explore the planets of the Solar System.

But above all else, NASA's greatest accomplishments have been in sending human beings into space, and being the agency that conducted the first manned missions to the Moon. In the coming years, NASA hopes to build on that reputation, bringing an asteroid closer to Earth so we can study it more closely, and sending manned missions to Mars.

Universe Today has many articles on NASA, including articles on its current administrators and the agency's celebrating 50 years of spaceflight.

For more information, check out history of NASA and the history of National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Astronomy Cast has an episode on NASA's mission to Mars.

Source: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today