[/caption]

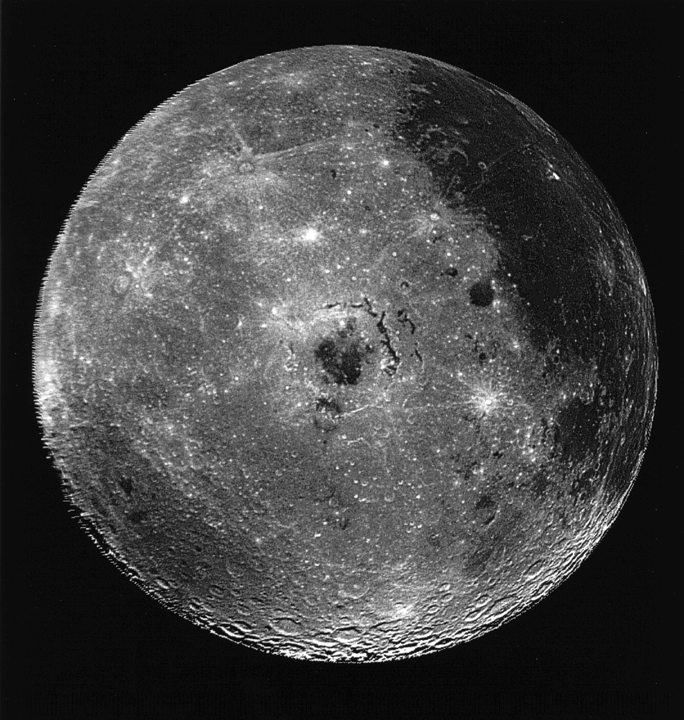

One of the legacies of the Apollo program is the rare lunar samples it returned. These samples (along with meteorites that originated from the moon and even one from Mars) can be radiometrically dated, and together they paint a picture a cataclysmic time in the history of our solar system. Over a period of time some 3.8 to 4.1 billion years ago, the moon underwent a fierce period of impacts that was the origin of most of the craters we see today. Paired with the “Nice model” (named after the French university where it was developed, not because it was pleasant in any way), which describes the migration of planets to their current orbits, it is widely held that the migration of Jupiter or one of the other gas giants migrations during this period, caused a shower of asteroids or comets to rain down upon the inner solar system in a time known as the “Late Heavy Bombardment” (LHB).

A new paper by astronomers from Harvard and the University of British Columbia disagrees with this picture. In 2005, Strom et al. published a paper in Science which analyzed the frequency of craters of various sizes on the lunar highlands, Mars, and Mercury (since these are the only rocky bodies in the inner solar system without sufficient erosion to wash away their cratering history). When comparing relatively young surfaces which had been more recently resurfaced to older ones from the Late Heavy Bombardment area, is that there were two separate, but characteristic curves. The one for the LHB era revealed a crater frequency peaking at craters near 100 km (62 miles) in diameter and dropping off rapidly to lower diameters. Meanwhile, the younger surfaces showed a nearly even amount of craters of all sizes measurable. Additionally, the LHB impacts were an order of magnitude more common than the newer ones.

The Strom et al. took this as evidence that two different populations of impactors were at work. The LHB era, they called Population I. The more recent, they called Population II. What they noticed was the current size distribution of main belt asteroids (MBAs) was “virtually identical to the Population 1 projectile size distribution”. Additionally, since the size distribution of the MBA is the same today, this indicated that the process which sent these bodies our way didn’t discriminate based on size, which would weed out that size and alter the distribution we observed today. This ruled out processes such as the Yarkovsky effect but agreed with the gravitational shove as a large body would move through the region. The inverse of this (that a process was selecting rocks to chuck our way based on size) would be indicative of Strom’s Population II objects.

However, in this paper recently uploaded to arXiv, Cuk et al. argue that the dates of many of the regions investigated by Strom et al. cannot be reliably dated and therefore, cannot be used to investigate the nature of the LHB. They suggest that only the Imbrium and Orientale basins, which have their formation dates precisely known from rocks retrieved by Apollo missions, can be used to accurately describe the cratering history during this period.

With this assumption, Cuk’s group reexamined the frequency of crater sizes for just these basins. When this was plotted for these two groups, they found that the power law they used to fit the data had “an index of -1.9 or -2 rather than -1.2 or -1.3 (like the modern asteroid belt)”. As such, they claim, “theoretical models producing the lunar cataclysm by gravitational ejection of main-belt asteroids are seriously challenged.”

Although they call into question Strom et al.’s model, they cannot propose a new one. They suggest some causes that are unlikely, such as comets (which have too low of impact probabilities). One solution they mention is that the population of the asteroid belt has evolved since the LHB which would account for the differences. Regardless, they conclude that this question is more open ended than previously expected and that more work will need to be done to understand this cataclysm.

It must have been incredibly tedious to process the data but the results are very interesting.