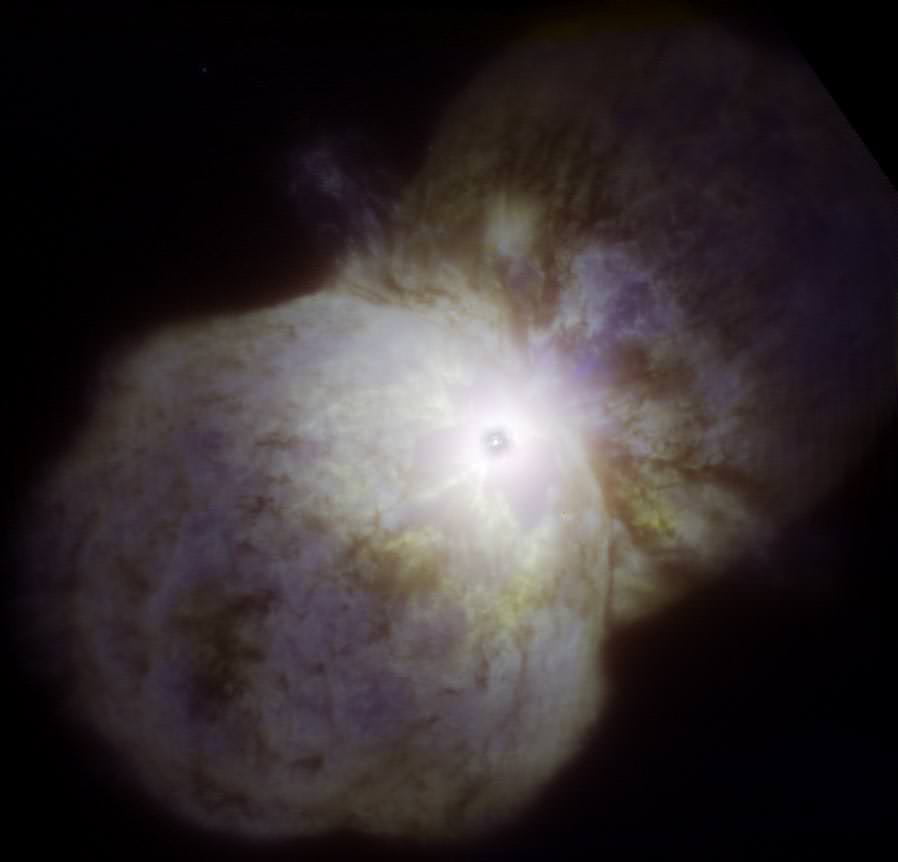

Caption: Eta Carinae as imaged by the Gemini South telescope in Chile with the Near Infrared Coronagraphic Imager (NICI) using adaptive optics to reduce blurring by turbulence in the Earth’s atmosphere. In this image the bipolar lobes of the Homunculus Nebula are visible with the never-before imaged “Little Homunculus Nebula” visible as a faint blue glow, mostly in the lower lobe. The Butterfly Nebula is visible (region circled) as the yellowish glow with dark filamentary structure close to, and mostly below/left, of the central star system (the central star system appears as a dark spot due to the coronagraphic blocking (occulting) disk used to eliminate the star’s bright glare).

I can’t seem to stop writing about Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) stars this week. And new research discussed at the AAS conference this week continues the trend. As part of a series of short talks on exploding stars, John Martin of the University of Illinois, Springfield spoke on his work with the LBV Eta Carinae.

Eta Carinae is often cited as one of the most likely stars of which we know to erupt as a core collapse supernova. It has a mass of nearly 100 times that of the sun. Although it hasn’t exploded as a supernova yet, its history has seen some pronounced brightenings. In 1843, Eta Carinae underwent a massive eruption that lasted 20 years and shed an estimated 20 times the mass of the sun. During that time, it became the second brightest stellar object in the sky (note: Eta Car is most readily visible from the southern hemisphere). It also emitted as much energy as a typical supernova although spread out over the duration instead of the quick burst as in a real supernova. Martin called this great eruption an “impostor supernova.”

To probe the internal structure of the outburst Martin and his team used the Near Infrared Chronographic Imager (NICI) on the Gemini South telescope in Chile. The use of infrared allowed the team to peer through the dusty outer layers of the nebula which absorb visible light. The device also used a device to block the light from the central star allowing the team to look through the glare and more directly explore the surrounding structure.

“The Gemini images have allowed us to perform something akin to an autopsy by peeling away the obscuring, outer dusty skin and giving us a glimpse of what’s inside,” Martin said. “In the process we’re finding things we have never imaged before and didn’t expect. It’s like finding your murder victim has a third lung, an extra liver, or something more exotic hidden away under their skin!”

During his presentation Martin also used an analogy of geology in which looking to deeper layers can give a chronological history since the inner layers would not have been expanding as long. Their infrared expedition revealed several structures never before seen in Eta Carinae. The region around the central star system contained wispy clouds which the team nicknamed the “Butterfly Nebula” (not to be confused with NGC 6302, which also has that moniker). They also discovered a smaller set of lobes which they dubbed the “Little Homunculus Nebula”. This structure was traced by mapping forbidden emission lines of Fe II.

In 2007, astronomers discovered the Cosmic Horseshoe, a gravitationally lensed system of galaxies about five-and-a-half…

Venus differs from Earth in many ways including a lack of internal dynamo driving global…

The journey to Mars will subject astronauts to extended periods of exposure to radiation during…

Anthropogenic climate change is creating a vicious circle where rising temperatures are causing glaciers to…

Satellites often face a disappointing end: despite having fully working systems, they are often de-orbited…

Astronomers have known for some time that nearby supernovae have had a profound effect on…