[/caption]

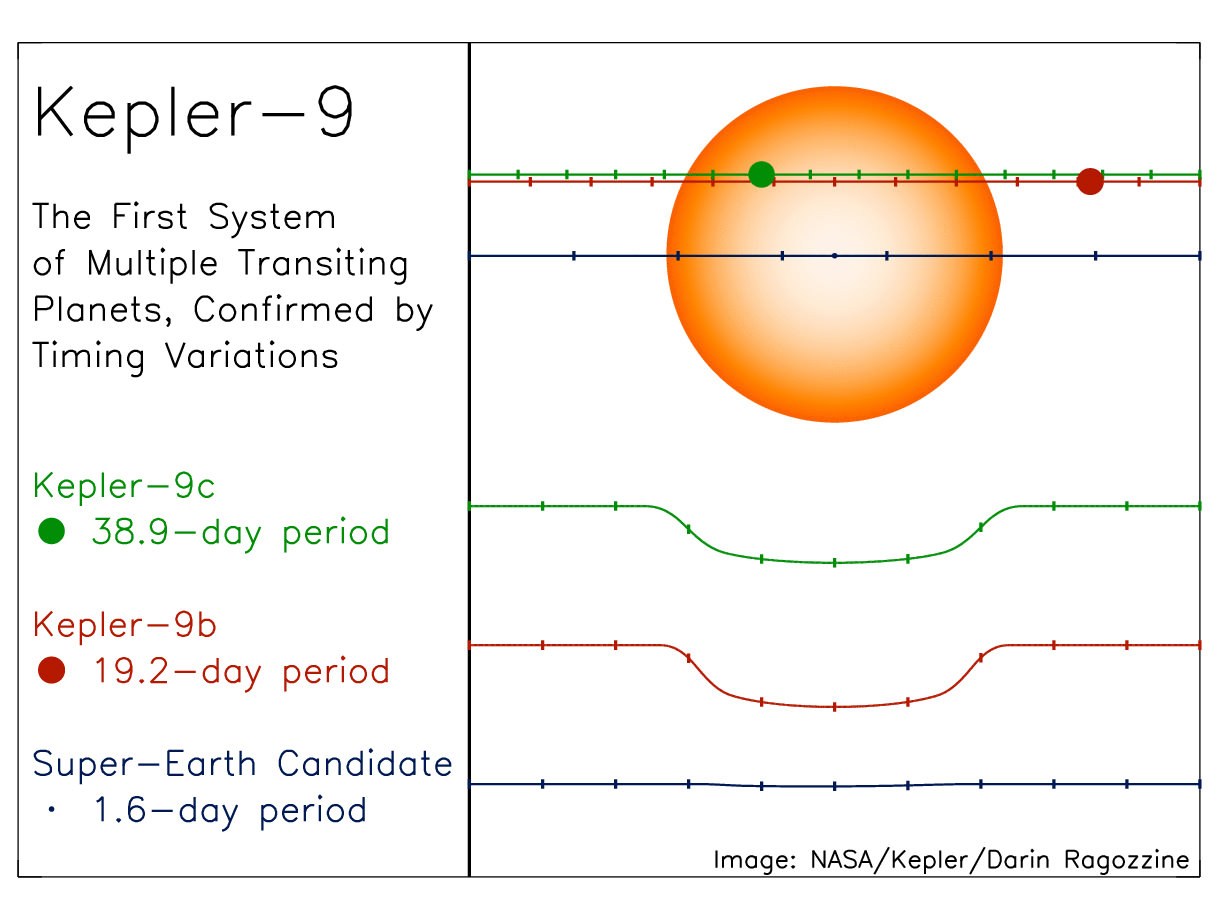

The Kepler mission has discovered a system of two Saturn size planets with perhaps a third planet that is only 1.5 times the radius of Earth. While the news of this discovery is tempered somewhat with the announcement by a team from the European Southern Observatory of a system with five confirmed Neptune-sized planets and perhaps two additional smaller planets, both discoveries highlight that the spacecraft and techniques astronomers are using to find exoplanets are getting the desired results, and excitingly exoplanet reseach now includes the study of multiplanet systems. This discovery is the first time multiple planets were found by looking at transit time variations, which can provide more information about planets, such as their masses.

“What is particularly special about this system, is that the variations in transit times are large enough, that we can use these transit timing to detect the masses of these bodies” said Matthew Holman, Kepler team lead for the study of star Kepler-9, speaking on the AAAS Science podcast. Additionally, these findings should provide the tools astronomers need to determine even more physical conditions of these planets — and others — in the future.

The inner world weighs in at 0.25 Jupiter mass (80 Earths) while the outer world is a slimmer 0.17 Jupiter mass (54 Earths).

The team analyzed seven months of data from the orbiting Kepler telescope, and the two large confirmed planets—Kepler-9b and Kepler-9c— are transiting the parent star at unstable rates. The planets’ 19.2- and 38.9-day transition periods are increasing and decreasing at average, respective rates of four and 39 minutes per orbit.

“One thing that caught our attention right off, is when we do preliminary estimates at the time of the transit, we saw large variations in this particular system. Not only did we see more than one planet transiting, but one planet seemed to be speeding up and one slowing down,” Holman said.

Because period one is roughly twice the other, they have a signature of what is called a 2:1 orbital resonance, where astronomers expect to see large timing variation, due to the orbital gravitational push and pull the systems has on all the objects.

“The variation in transit times depend upon the masses of the planets,” Holman told reporters in a news conference announcing the findings. “The larger the mass the larger the variations. These variations allows us to determine the mass of the objects and we can confirm that they are planets.”

The team also confirmed the objects were planets with radial velocity observations with the Keck I telescope.

The third planet, with a mass several times that of the Earth, is transiting the star in a more interior orbit, but further analysis will be necessary to confirm that this signature is actually a planet.

“We are being very careful at this point to only call it a planet candidate, rather than a confirmed planet,” Holman said. “If it is confirmed it would only have a radius of about 1.5 that of Earth’s. It has a much shorter orbital period of 1.6 days, so it is very close to its host star, so we should be able to see evidence of many transits.”

Holman added that this discovery — regardless of whether they are able to confirm that this is a planet or not — highlights the sensitivity of Kepler to very small signatures.

Holman said the planets have probably migrated to be closer to the star from where they started out when they formed. “Likely they formed with the star, but likely they formed farther out at the “snow line” several times farther away from the star than the Earth is, and by a dynamical process move in closer,” he said in the Science podcast.

The resonance is a signature that some kind of migration had occurred, called convergent migration, where planets are moving towards the star and also coming closer to each other.

From all the transit timing information that has been gathered so far, astronomers are piecing together the migration history of this planetary system. “The whole history of that system may be encoded in the information we have,” said Alycia Weinberger, from the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism at the Carnegie Institution. “Isn’t it cool that what the planetary system looks like today has much to tell us about its history?”.

Kepler looks for the signatures of planets by measuring tiny decreases in the brightness of stars when planets cross in front of, or transit them. The size of the planet can be derived from the change in the star’s brightness. In June, mission scientists announced the mission has identified more than 700 planet candidates, including five systems with more than one planet candidate. This is the first of those systems to be confirmed.

Kepler principal investigator William Borucki said the team is working hard to get these candidates “turned into confirmed planets.”

Asked about why the public seems to be so interested in the Kepler mission, Borucki said, “We addressing a very important question, which is, are there other earths out there and are they frequent? Any answer is important. If we get zero that might mean there is very little life out there in the universe.”

Sources: Science, AAAS Science podcast, NASA,

Cool!

Bummer, the rumor is that they will post an arxiv paper on the likelihood of the 1.5 Earth-radius (2 Earth-gravities, 3 Earth-masses) planet tonight: still no paper!?

Astro-ph doesn’t come out until 3 hours from now…

I see the paper on KOI-377 has been posted: http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/1008/1008.4393v1.pdf

Thank ye all! Title “… STRONG EVIDENCE FOR A SUPER-EARTH-SIZE PLANET …” [drools -> reads]

@JON HANFORD,

Thanks for that paper — you beat me to it! 🙂

The graphic for this story – yes, I know it’s from NASA/Kepler, not UT – bothers me. Those graphs across the bottom are supposed to be light curves, I think, because the y-axis is brightness. But then the x-axis should be time. And if it’s time, the dip in the red curve for Kepler-9b should be a lot narrower. Here’s why.

As 9b orbits with half the period of 9c, Kepler’s 3rd Law tells us 9b is traveling about 1.25 (actually, 2^(1/3)) times faster. The diagram suggests both planets transit Kepler9 at about the same “latitude” so they both travel the same distance across the front of the star. Since 9b is traveling 1.25 times faster, is should take only 1/1.25 or about 0.8 times as long as 9c. So the red dip should be 0.8 the width of the green dip.

NASA/Kepler properly included the change in dip-width in the other light curve graphic from Thursday’s press conference

http://www.nasa.gov/images/content/476590main_TransitSignature_Mu10D0C0C.jpg

As expected, the longer the orbital period, the slower the speed of the planet, the longer it takes to transit and the wider the dip in the light curve. Perfect.

“Oh, c’mon. You’re splitting hairs…” you might say. Sure, that’s my mathgeek, astrogeek side. But my teaching side knows these NASA-generated graphics will soon start appearing in introductory “astro 101” PPT presentations as instructors struggle to include “the latest stuff” in their courses. Students will see them and if they take the time to think carefully about the graphic, they’ll discover it’s wrong. Yes, scientists are wrong again. How can you trust anything they say? Oh, well.

Except a good fraction of astro 101 students, up to 40% by some estimates, will become school teachers. And this is the ONLY science course they will EVER take. And they’re your kids’ teachers. Damn.

Those of us lucky enough to have jobs where we get to make scientific discoveries must take great care when we present science to non-experts. We must look at it from THEIR perspective, not ours, because they will not make any minor corrections. As a presenter at the recent Cosmos in the Classroom meeting said, “if you can’t speak astronomy like your students do, you’re going to have a difficult time teaching.” As data visualization experts advise, be sure to ask a non-expert to look at the graphics (and graphs) you create. If your goal is to help people understand what you discovered, help them understand.

Peter