[/caption]

You knew it was only a matter of time until the hunt for extrasolar planets joined the Zooniverse family of Citizen Science projects. And the time has now arrived for your chance to make one of the biggest discoveries of the 21st century by finding other planets out there in the Universe.

Planet Hunters is the latest addition to the Zooniverse, and users will help scientists analyze data taken by NASA’s Kepler mission, the biggest, badest exoplanet hunting telescope in space. The project goes live on December 16 at http://www.planethunters.org.

“The Kepler mission has given us another mountain of data to sort through,” said Kevin Schawinski, a Yale University astronomer and Planet Hunters co-founder. Schawinski was one of the original forces behind Galaxy Zoo, the citizen science project that started it all back in 2007, which enlisted hundreds of thousands of Web users round the world to help sort through and classify a million images of galaxies taken by a robotic telescope.

The Kepler telescope has been in space since 2009, continually monitoring nearly 150,000 stars in the constellations Cygnus and Lyra, recording their brightness over time. In June of this year, the Kepler team announced they had found over 750 exoplanet candidates in just the first 43 days of the spacecraft’s observations.

They also just announced they will make an early release of a complete 3 months of observations early in 2011, which will contain light curves for approximately 165,000 stars, most of which are late-type Main Sequence stars.

“The Kepler mission will likely quadruple the number of planets that have been found in the last 15 years, and it’s terrific that NASA is releasing this amazing data into the public domain,” said Debra Fischer, a Yale astronomer and leading exoplanet hunter.

Although Planet Hunters is not tied directly to the Kepler mission, the website will serve as a complement to the work being done by the Kepler team to analyze the data, the team said.

Granted, the Citizen Scientists looking for extrasolar planets will be doing a search akin to looking for a needle in a haystack. But its one of the most exciting needles to be searching for.

Because of the huge amount of data being made available by Kepler, astronomers rely on computers to help them sort through the data and search for possible planet candidates. “But computers are only good at finding what they’ve been taught to look for,” said Meg Schwamb, another Yale astronomer and Planet Hunters co-founder, “whereas the human brain has the uncanny ability to recognize patterns and immediately pick out what is strange or unique, far beyond what we can teach machines to do.”

Galaxy Zoo project has shown how successful this concept of using a network of global volunteers can be, as the Citizen Scientists has helped the Galaxy Zoo team publish over 20 papers about galaxy shapes and distributions, as well as making some unusual discoveries, like Hanny’s Voorwerp.

To participate, you don’t need to have any astronomical or exoplanet expertise. When users log on to the Planet Hunters website, they’ll be asked to answer a series of simple questions about one of the stars’ light curves — a graph displaying the amount of light emitted by the star over time — to help the Yale astronomers determine whether it displays a repetitive dimming of light, identifying it as an exoplanet candidate.

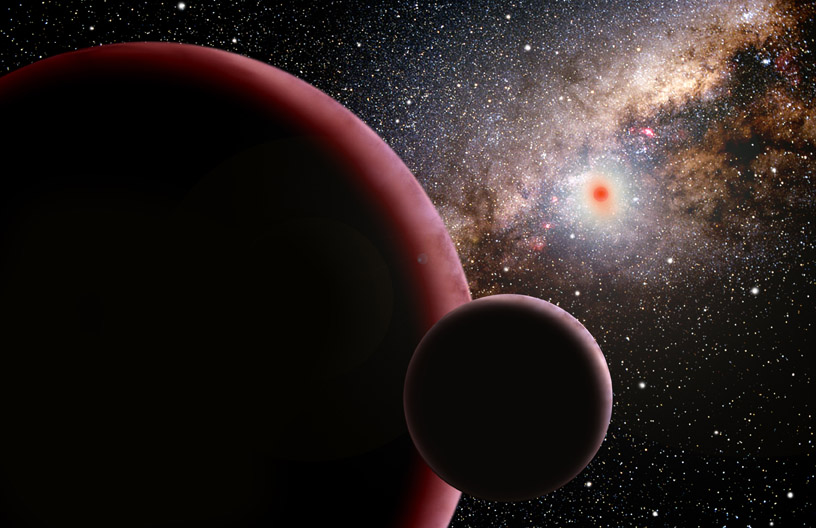

And exoplanet research is one of the hottest topics in astronomy today. Over 500 planets have been found orbiting other stars since 1995. Most of these are large, Jupiter-like planets, but astronomers are refining their searches to try and find smaller planets more the size of Earth.

“The search for planets is the search for life,” Fischer said. “And at least for life as we know it, that means finding a planet similar to Earth.” Scientists believe Earth-like planets are the best place to look for life because they are the right size and orbit their host stars at the right distance to support liquid water, an essential ingredient for every form of life found on Earth.

The point of citizen science is to actively involve people in real research,” Schawinski said. “When you join Planet Hunters, you’re contributing to actual science — and you might just make a real discovery.”

I tried it, and I love it! While classifying I actually found a star with a very, very obvious transit, and as I result I was actually able to estimate the planet’s orbital period, which was approximately 12 days. Also, as a bonus, when I got done classifying the star, I got a message that said that it was a Kepler favorite. Dunno what that was referring to, but HOT DANG am I proud!

I feel that projects like this presages how much of astronomy will be done in the future, as programs like LSST will be generating multiple terabytes of info per day. In addition to newly generated databases, many large archival datasets will also be made available to the public via the internet, and can be mined similar to the SDSS-Galaxy Zoo project.

(It may also help level the playing field for amateur comet, asteroid, nova and supernova hunters. 😀 )

Alright, now I’m a planet hunter. They could have shown more examples at the beginning. They give you simulated ones in the process, in one I noticed something but I didn’t mark it. I’m not very confident if a star is pulsating or it’s a dip, but I guess it’s getting better. Then, there are some odd ones. I have surprisingly favorited a lot of ones.

This is great stuff. Trying to help out right now..