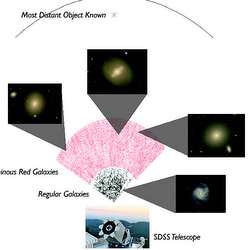

A schematic view of the new SDSS three-dimensional map. Image credit: Hogg/SDSS-II collaboration. Click to enlarge

Astronomers from UC Berkeley have created the most comprehensive three-dimensional map of the Universe ever published. Amazingly, this map is merely a slice containing 1/10th of the northern hemisphere. It contains 600,000 galaxies and extends out 5.6 billion light-years into space. This map allows astronomers to study evidence for dark energy – the mysterious force accelerating the expansion of the Universe.

A team of astronomers led by Nikhil Padmanabhan and David Schlegel has published the largest three-dimensional map of the universe ever constructed, a wedge-shaped slice of the cosmos that spans a tenth of the northern sky, encompasses 600,000 uniquely luminous red galaxies, and extends 5.6 billion light-years deep into space, equivalent to 40 percent of the way back in time to the Big Bang.

Schlegel is a Divisional Fellow in the Physics Division of Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and Padmanabhan will join the Lab’s Physics Division as a Chamberlain Fellow and Hubble Fellow in September; presently he is at Princeton University. They and their coauthors are members of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS), and have previously produced smaller 3-D maps by using the SDSS telescope in New Mexico to painstakingly collect the spectra of individual galaxies and calculate their distances by measuring their redshifts.

“What’s new about this map is that it’s the largest ever,” says Padmanabhan, “and it doesn’t depend on individual spectra.”

The principal motive for creating large-scale 3-D maps is to understand how matter is distributed in the universe, says Padmanabhan. “The brightest galaxies are like lighthouses – where the light is, is where the matter is.”

Schlegel says that “because this map covers much larger distances than previous maps, it allows us to measure structures as big as a billion light-years across.”

The variations in galactic distribution that constitute visible large-scale structures are directly descended from variations in the temperature of the cosmic microwave background, reflecting oscillations in the dense early universe that have been measured to great accuracy by balloon-borne experiments and the WMAP satellite.

The result is a natural “ruler” formed by the regular variations (sometimes called “baryon oscillations,” with baryons as shorthand for ordinary matter), which repeat at intervals of some 450 million light-years.

“Unfortunately it’s an inconveniently sized ruler,” says Schlegel. “We had to sample a huge volume of the universe just to fit the ruler inside.”

Says Padmanabhan, “Although the universe is 13.7 billion years old, that really isn’t a whole lot of time when you’re measuring with a ruler that’s marked only every 450 million light-years.”

The distribution of galaxies reveals many things, but one of the most important is a measure of the mysterious dark energy that accounts for some three-fourths of the universe’s density. (Dark matter accounts for roughly another 20 percent, while less than 5 percent is ordinary matter of the kind that makes visible galaxies.)

“Dark energy is just the term we use for our observation that the expansion of the universe is accelerating,” Padmanabhan remarks. “By looking at where density variations were at the time of the cosmic microwave background” – only about 300,000 years after the Big Bang – “and seeing how they evolve into a map that covers the last 5.6 billion years, we can see if our estimates of dark energy are correct.”

The new map shows that the large-scale structures are indeed distributed the way current ideas about the accelerating expansion of the universe would suggest. The map’s assumed distribution of dark matter, which although invisible is affected by gravity just like ordinary matter, also conforms to current understanding.

What made the big new 3-D map possible were the Sloan Digital Sky Survey’s wide-field telescope, which covers a three-degree field of view (the full moon is about half a degree), plus the choice of a particular kind of galactic “lighthouse,” or distance marker: luminous red galaxies.

“These are dead, red galaxies, some of the oldest in the universe – in which all the fast-burning stars have long ago burned out and only old red stars are left,” says Schlegel. “Not only are these the reddest galaxies, they’re also the brightest, visible at great distances.”

The Sloan Digital Sky Survey astronomers worked with colleagues on the Australian Two-Degree Field team to average the color and redshift of a sample of 10,000 red luminous galaxies, relating galaxy color to distance. They then applied these measurements to 600,000 such galaxies to plot their map.

Padmanabhan concedes that “there’s statistical uncertainty in applying a brightness-distance relation derived from 10,000 red luminous galaxies to all 600,000 without measuring them individually. The game we play is, we have so many that the averages still give us very useful information about their distribution. And without having to measure their spectra, we can look much deeper into space.”

Schlegel agrees that the researchers are far from achieving the precision they want. “But we have shown that such measurements are possible, and we have established the starting point for a standard ruler of the evolving universe.”

He says “the next step is to design a precision experiment, perhaps based on modifications to the SDSS telescope. We are working with engineers here at Berkeley Lab to redesign the telescope to do what we want to do.”

“The Clustering of Luminous Red Galaxies in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey Imaging Data,” by Nikhil Padmanabhan, David J. Schlegel, Uros Seljak, Alexey Makarov, Neta A. Bahcall, Michael R. Blanton, Jonathan Brinkmann, Daniel J. Eisenstein, Douglas P. Finkbeiner, James E. Gunn, David W. Hogg, ??bf?eljko Ivezić, Gillian R. Knapp, Jon Loveday, Robert H. Lupton, Robert C. Nichol, Donald P. Schneider, Michael A. Strauss, Max Tegmark, and Donald G. York, will appear in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is now available online at http://arxiv.org/archive/astro-ph.

SDSS is managed by the Astrophysical Research Consortium for the Participating Institutions, which are the American Museum of Natural History, Astrophysical Institute Potsdam, University of Basel, Cambridge University, Case Western Reserve University, University of Chicago, Drexel University, Fermilab, the Institute for Advanced Study, the Japan Participation Group, Johns Hopkins University, the Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics, the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology, the Korean Scientist Group, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (LAMOST), Los Alamos National Laboratory, the Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy (MPIA), the Max-Planck-Institute for Astrophysics (MPA), New Mexico State University, Ohio State University, University of Pittsburgh, University of Portsmouth, Princeton University, the United States Naval Observatory, and the University of Washington.

SDSS funding is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the Participating Institutions, the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Japanese Monbukagakusho, the Max Planck Society, and the Higher Education Funding Council for England. Visit the SDSS web site at http://www.sdss.org/.

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California. Visit our website at http://www.lbl.gov.

Original Source: Berkeley Lab

Just a few thoughts that aggravate me: Accepting the big bang theory and an ever expanding universe, why has the cosmological center never been identified as being a space void of nothing? Assuming a center point of the big bang, there should be cosmos that are acclerating opposite from us at a rate twice the velocity we are from the center. Assuming all energy was not expelled at a constant rate at the beginning (hence, many galaxies are ahead of us in expansion), might it be possible that the very last formed galaxies, matter and particles will not achieve enough break away velocity, and at some point will collapse back upon itself? Not much unlike an atom shedding an outter shell and returning to a stable state, or even a manmade explosion in which the very center of the explosion tends to have a return implosion effect. Perhaps there is a point around the cosmological sphere in which some matter will not achieve break away velocity from the center point. Perhaps the universe for the most part is expanding, yet a part is actually contracting.