[/caption]

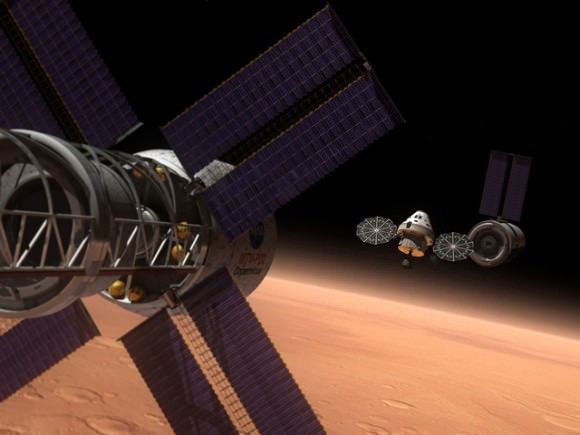

NASA has made a decision on their next crew vehicle, and now have plans to develop a “new” spacecraft called the Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle (MPCV). NASA Administrator Charles Bolden announced today that the system will be based on designs originally planned for the Orion Crew Exploration Vehicle which was being built to return humans to the Moon. This decision shouldn’t come as a surprise, and it is not a huge leap or a big change for NASA — the Orion crew vehicle has been in continued development by Lockheed Martin and the company was already making changes in the vehicle for a proposed asteroid mission.

“We are committed to human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit and look forward to developing the next generation of systems to take us there,” Bolden said. “The NASA Authorization Act lays out a clear path forward for us by handing off transportation to the International Space Station to our private sector partners, so we can focus on deep space exploration. As we aggressively continue our work on a heavy lift launch vehicle, we are moving forward with an existing contract to keep development of our new crew vehicle on track.”

NASA said that Lockheed Martin will continue work on development of the MPCV, since they already have a test article built of the Orion. The spacecraft will carry four astronauts for 21-day missions and be able to land in the Pacific Ocean off the California coast. The spacecraft will have a pressurized volume of 690 cubic feet, with 316 cubic feet of habitable space.

It will serve as the primary crew vehicle for missions beyond low Earth orbit and be capable of conducting regular in-space operations (rendezvous, docking, extravehicular activity) in conjunction with payloads delivered by a launch system for missions beyond LEO. The MPCV could also be a backup system for ISS cargo and crew delivery.

A 21-day mission might get astronauts to a nearby asteroid, but there would not be enough time for a longer-duration, far-away asteroid mission and certainly not to Mars. It would get you to the Moon, allowing astronauts to stay a couple weeks and then return home, which was what Constellation was going to do in its first stages.

UPDATE: During a press conference today, Doug Cooke, associate administrator for NASA’s Exploration Systems Mission Directorate said that the approach on the MPCV vehicle is that it primarily will be for launch and entry with in-space capabilities for only certain periods of time. “For long term missions, we would assume that we have an in-space habitation in a larger compartment or module since the crew would need more space for longer periods of time. So whether they are going to lunar orbit or near earth asteroids, this vehicle would be maintained in a dormant mode while the crew would be in another volume that would be capable of longer term use, but this vehicle would be used as launching to a larger volume, or for reentry.”

The Orion vehicle at one time had been pegged to be a rescue vehicle for the International Space Station. Cooke said that this new vehicle is not being designed for that, but another vehicle could be in designed for that.

One big selling point is that the new MPCV is designed to be 10 times safer during ascent and entry than its predecessor, the space shuttle.

“This selection does not indicate a business as usual mentality for NASA programs,” said Cooke, “The Orion government and industry team has shown exceptional creativity in finding ways to keep costs down through management techniques, technical solutions and innovation.”

Now, NASA just needs a rocket that can take the MPCV somewhere — as well as a new name for the MPCV. (Cooke said a name for the vehicle hasn’t been their top priority.) Cooke said they hope to make an announcement in July about the launch system that will be used.

The current rumor is that the new Congressional-mandated launched system will be based on the Ares 5, the heavy-lifter NASA began designing in 2006 for manned Moon missions which was canceled by President Obama along with Orion…

316 cubic feet of habitable space is not much. Is there any research into adding an inflatable from Bigelow? A Sundancer would provide an additional 180 cubic meters living space and provide for better mental and physical health of the crew. It could be inflated after they were underway and parked in earth orbit on return for possible repeat use. From what I’ve read on Bigelow’s site, it would provide more protection for the crew from radiation or impacts too.

It’s not like they’ll inhabit the capsule for extended periods. If it were going somewhere other than ISS, it would probably have a mission module or some other complex to go to.

Indeed it should, but no one is saying that, so far. Right now, the idea seems to be twin Orions docked together to reach a NEO…and for an uncomfortably long time…

I take that back. There is *some* sanity happening here:

http://www.hobbyspace.com/nucleus/index.php?itemid=29739

I’m listening to a press conference as I write this reply and have updated the article — that question was asked during the press conference. See update above.

Thanks, Nancy! Question answered.

Depends if Bigelow gets bought out by Lockheed or Boeing, and they figure out a way to work it into pork-barrel politics.

What was old is new again huh? Looks like an upgrade of the capsules instead of a next generation space vehicle.

Capsules are the ideal spacecraft really. Some things we learned from the shuttle era:

· Wings don’t work in space.

· It defeats the purpose of a HLV if most of the payload has to come back down.

· Complicated spacecraft are complicated.

· The Shuttle did not live up to the goals for which it was designed to achieve — it did not dramatically lower the cost of spaceflight, and it’s reusability is not as easy as was hoped (compare the concept art of the Orbiter Processing Facility to what really happened — complicated spacecraft are complicated :c)

I think it’s clear that the Russians had it right the whole time. Design a small or medium-lift rocket for the capsule, which serves as just a transport to the destination. And have that destination be the job of heavy lift rockets to put in orbit.

The Shuttle wasn’t designed as a spacecraft though, but as a reusable launcher:

– “· Wings don’t work in space.”

We knew this before the shuttle =D, and they were solely used for landing.

If you want to go for a suboptimal Shuttle technology, the main engines are a better choice as they had to cover sea level to space. No nozzle engine can do this optimally, you need spike engines to do this.

– “defeats the purpose of a HLV”, “complicated”.

But it doesn’t defeat the purpose of a reusable LV, nor will they be much less complicated on the system level.

The Ares-5 derivative will do the same reuse. Even SpaceX aim to do this for lowest cost. It looks to be future standard technology; the Shuttle was a premature attempt to do this.

– “The Shuttle did not live up to the goals for which it was designed to achieve.”

I would say it lived up exactly to the goals, and even overshot them (efficiency of main engines). It was the goals that were conflicting (military polar orbits and large loads vs civilian equatorial orbits and cheap loads).

Of course we want to have other craft for other purposes. The ISS is constructed, the STS has no specific purpose anymore. Its legacy lives on in the US robotic spy craft.

Disagree. Capsules are not the best spacecraft. Going back to crashed landing in the water is not a superior solution to gliding into a runway. The best spacecraft is one that stays in space (note – not abandoned in space)…. what we’re talking about here is a landing craft

+ Wings in space were never expected to work. The reason for the wings on the shuttle was landing.

+ Shuttle wasn’t intended to be a heavy lifting vehicle. It was intended to be a…. shuttle.

+ All spacecraft are complicated.

+ the shuttle actually performed miraculously. 133 flights over 30 years. Sorry, that is an AWESOME record.

I disagree that the Russians “had the right idea the whole time”. They have basically become contractors to NASA and have been using their 1960’s era designs. Do they work? Sure as hell they do. Our 1960s stuff would work too. Hell, if we made new shuttles they’d work too.

The shuttle wasn’t an STO vehicle. This isn’t an STO vehicle. Since we retired the Saturn V’s a long time ago we gave up that level of lifting ability. I agree we need to get it back. However the thing now is cheap, reusability…. Stuff that makes NASA beg and plead for its ½% of the federal budget.

Am I against this? No, not “against” it… just not pleased that’s the path we’re choosing. I want to see an effort to move a colony to the moon…. Not 2 guys in a tin can…

How do we do that? HLVs… put giant amounts of material into orbit. Build a station that isn’t in LEO to use as a stepping stone to the moon, mars and beyond… bascially the plan NASA put forth in 1958 😉

“Wings don’t work in space.

Um, I think they knew that. Wings (though they didn’t really need the cross range of deltas) were part of the price of re-useability. (though non-winged, vertical take of and landing re-useable launchers are also possible) It’s the same obvious reason you don’t put landing gear on cruise missiles.

“It defeats the purpose of a HLV if most of the payload has to come back down.”

I…don’t understand that assertion. Shuttle wasn’t built to justify an HLV, compete with one, or act as a re-useable one.

“Complicated spacecraft are complicated.”

It remains to be seen how ‘simple’ a deep-space Orion will be.

“The Shuttle did not live up to the goals for which it was designed to achieve — it did not dramatically lower the cost of spaceflight, and it’s reusability is not as easy as was hoped”

On that, you are quite correct. However, that doesn’t prove the superiority of ballistic capsules, or invalidate RLVs in general, just that particular iteration of an RLV.. The lesson of the Shuttle is; “Don’t design your RLVs *to be like this.” (The floor fell out of teh then-Soviet economy, before Buran taught them that…though they did get a good stand-alone launcher out of the deal {Energia] even though they only flew it twice.)

“I think it’s clear that the Russians had it right the whole time. Design a small or medium-lift rocket for the capsule, which serves as just a transport to the destination. And have that destination be the job of heavy lift rockets to put in orbit.”

I have never believed in the ‘separate crew and cargo’ concept (I doubt FedEx and UPS pilots do either) however, there is no reason a *small* RLV cannot replace existing transport of people to LEO. The more you intend to do it, the more an RLV makes economic sense.

Re-useable ‘heavy’ launchers are technically possible as well, but it will take quite some time before there’s a need to justify their development…we don’t even need a new *expendable* HLV at his time…

For the non-imperial people:

690 cubic feet = 19.5 m^3

316 cubic feet = 8.9 m^3

Almost as much as Dragon for the pressurized, but more for unpressurized.

(From the SpaceX site) Payload Volume: 10 m3 (245 ft3) pressurized, 14 m3 (490 ft3) unpressurized.

What about solar storms? We were very lucky that none of the Apollo crews were fried when they ventured out from under the Van Alan Belt: this capsule better be hardened sufficiently to keep the crew safe from coronal mass ejections!

What about solar storms? We were very lucky that none of the Apollo crews were fried when they ventured out from under the Van Alan Belt: this capsule better be hardened sufficiently to keep the crew safe from coronal mass ejections!

Ooops!

I don’t think it will though. I can see from the web that people want to assess NEOs due to this, but as of 2008 there where only a handful of NEOs that were reachable with the more capable Orion (210 days):

“Out of the then-current JPL catalogue, nine candidate NEOs were found that presented good opportunities for piloted CEV missions within the 2020 to 2035 time frame. Three of the NEO targets were reachable with mission durations of 150 days and all nine were reachable with mission lengths of 180 days (Fig. 4) (Table 1). Several NEOs were attainable under 90 and 120 day mission scenarios, but not before 2035. However, with the expected increase of the known NEO population by more than a factor of 50 from the contributions of the Pan-STARRS and the LSST systems (NASA Report to Congress 2007), it is

expected that the number of viable mission targets will also increase significantly.1 This may also result in more frequent launch opportunities for human NEO missions within the

desired 2020 to 2035 time frame.” [My bold.]

I guess we will have to wait for the SpaceX Dragon capsule (max endurance capability 2 years) before NASA does anything else than rounding the Moon (again).

What people do not seem to realize is that interplanetary space can be very lethal. A decent solar flair can send enough Kev energy charged particles to turn the crew of a spacecraft into dead bodies within hours. This capsule does not appear to be very shielded, and you will need about 1kg of shield for every square cm of containment wall of the cabin. Based on the specs for this capsule the shielding mass could be up to 27 metric tons. This is capsule would probably not be the main compartment during flight, so shielding could be up to 100 or 200 tons.

Even flying to the moon is a bit risky, but for a week mission we can usually predict if the sun will have a nasty solar flair storm. For a multi-week or months long interplanetary mission the risks are far larger.

LC

Solar storms, now with extra flair. =D

But you are correct. I don’t know how they (or Space-X) will handle that part. Most likely they want to add a larger living volume for transit and a storm shelter against solar CMEs.

[Added in posting: I see this is discussed below.]

It is a major problem with the whole idea of piloted interplanetary space

flight. There is no way out of the need for considerable mass that acts as

shielding. One might of course use a large magnetic field to do the trick,

but you need a hefty power source and so forth.

One thought is to put the crew cabin in a section that has a reaction mass

jacket around it, essentially a tubular dewar flask that holds hydrogen.

Either that or the tank is otherwise designed to most often face the sun to

shadow the cabin. The reason for hydrogen is I assume any interplanetary

craft will be nuclear propelled with an ISP of 1000 to 2000 seconds. This

hydrogen is used in the final deceleration to Mars. Then a second tank

pumps its reaction mass into the shielding tank, and that second tank is

discarded. That reaction mass is used to return to Earth, and then maybe

various wastes which have built up in the spacecraft fill the tank or some

other disposed substitute is used.

LC

I found NASA’s Jan 2011 report “Preliminary Report Regarding NASA’s Space Launch System and Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle”.

There I note that the MPCV will “Be evolvable to serve as the primary crew vehicle for missions beyond cis-lunar space.” (p 18).

Also, NASA acknowledges that they have have been doing skunk works instead of acting out the point of law (?) of the NASA Authorization Act of 2010:

“The Authorization Act also calls for the MPCV to be capable of providing, as a back-up to commercial crew and international partner services, crew and cargo transportation to and from the ISS. The beyond-LEO Orion also meets this requirement of contingency transportation to and from the ISS. Although the beyond-LEO Orion design does not include volume in the SM for large unpressurized cargo items for ISS, this is enabled in the Orion PDR design through mission kitting that would remove consumables tanks not needed for back-up ISS transportation missions and replace the volume with cargo capability. Other mission-specific design variations can be designed for the beyond-LEO Orion to enable support for the variety of other missions described in the Act, such as performing EVA, rendezvous and docking, and operating in conjunction with payloads delivered by the SLS or other vehicles in preparation for missions beyond LEO.

Given the applicability of the current Orion work, NASA’s Reference Vehicle Design for MPCV is the beyond-LEO version of the current Orion. It must be emphasized for clarity that the MPCV design will be optimized for beyond-LEO exploration capability. Any contingency utilization as a backup-LEO crew vehicle will represent a highly inefficient vehicle usage.”

So it can be re-purposed for ISS which was its original purpose, for extra cost and for suboptimal use (“highly inefficient vehicle usage”).

It still is Orion, it was never cancelled. The moon phase was, the launcher was .. the capsule never was as it was needed to replace the shuttle. Obama cancelled NASA’s moon-oriented Constellation program, which included the Ares I rocket, last year and ordered a new plan that favors asteroid and Mars exploration. Lockheed Martin, for example, has performed an in-depth study on linking multiple Orion capsules together and sending them on a manned mission to an asteroid. The Endevour launch the other day saw NASA state that they were excited by seeing Orion in their testing area and that they think it’s capable of 220+ days with 3 crew members interlinking the capsules…. He even joked that Mars didn’t seem to far away now.

Sigh. I could live with continuing Orion work, as long as it was understood that it would not go to LEO on any launcher that isn’t already operational, or upgrades of same…

Or not to go beyond LEO without orbital re-fueling or docking with a non-expendable, refuelable ‘tug’ of some sort…

It’s using Orion/MPCV as a foot in the door to a new, unnecessary HLV that really worries me.

I think the idea of a capsule is all well and fine…for liftoff and re-entry. IMHO the ISS should have a slew of them docked for escape pod purposes anyway.

I feel they would be much better served with an actual space vehicle – one that’s designed not to leave space – and incorporate the capsules as part of a LM/return system for the ship while it’s on a mission. Using them as the primary vehicle instead of just what they’re best suited for seems a bit silly. A little speed boat may be the best suited for getting in and out of the harbor, but I’m sure as heck not going to ride that thing across the ocean.