[/caption]

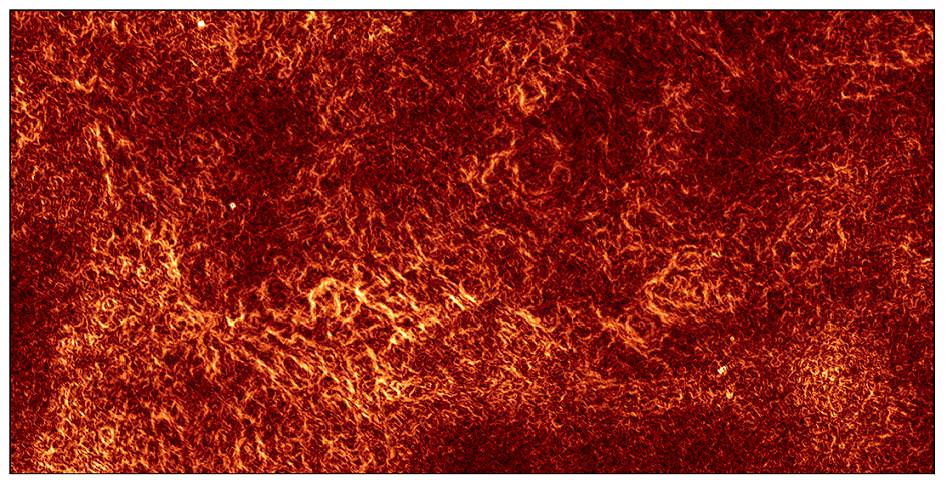

All of the space that surrounds us isn’t empty. We’ve always known the Milky Way was filled with great areas of turbulent gas, but we’ve never been able to see them… Until now. Professor Bryan Gaensler of the University of Sydney, Australia, and his team used a CSIRO radio telescope in eastern Australia to create this first-ever look which was published in Nature today.

“This is the first time anyone has been able to make a picture of this interstellar turbulence,” said Professor Gaensler. “People have been trying to do this for 30 years.”

So what’s the point behind the motion? Turbulence distributes magnetism, disperses heat from supernova events and even plays a role in star formation.

“We now plan to study turbulence throughout the Milky Way. Ultimately this will help us understand why some parts of the galaxy are hotter than others, and why stars form at particular times in particular places,” Professor Gaensler said.

Employing CSIRO’s Australia Telescope Compact Array because “it is one of the world’s best telescopes for this kind of work,” as Dr. Robert Braun, Chief Scientist at CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, explained, the team set their sights about 10,000 light years away in the constellation of Norma. Their goal was to document the radio signals which emanate from that section of the Milky Way. As the radio waves pass through the swirling gas, they become polarized. This changes the direction in which the light waves can “vibrate” and the sensitive equipment can pick up on these small differentiations.

By measuring the polarization changes, the team was able to paint a radio portrait of the gaseous regions where the turbulence causes the density and magnetic fields to fluctuate wildly. The tendrils in the image are also important, too. They show just how fast changes are occurring – critical for their description. Team member Blakesley Burkhart, a PhD student from the University of Wisconsin, made several computer simulations of turbulent gas moving at different speeds. By matching the simulations with the actual image, the team concluded “the speed of the swirling in the turbulent interstellar gas is around 70,000 kilometers per hour — relatively slow by cosmic standards.”

Original Story Source: CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science News Release. For Further Reading: Low Mach number turbulence in interstellar gas revealed by radio polarization gradients.

Wow, this is great!

Truly, first time I see such astronomy pic – amazing!

I hope this technique ‘catches on’ and is expanded to include a whole sky view.

That is fantastic! Another way to see the universe. I do hope we can get a gravitational wave observatory going, because I think we could see into another dimension or two. We might find we have neighbors!

The LIGO (Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory) gravity wave detector experiment by CalTech and MIT has been up and running for several years now – starting in 2001 http://www.ligo.caltech.edu/

The Advanced LIGO (Mk II) seems to have the best chance of finding gravity waves?

Meanwhile there are a plethora of other gravity wave experiments either currently running or having been run with questionable results.

There is the French-Italian experiment VIRGO

Then there is the TAMA detector in Japan.

And the English-German GEO 600.

The ACIGA detector is in Australia.

The ALEGRO detector was built by the Louisiana State University.

Random noise continues to be a problem with these experiments. Meanwhile, Universe Today has been HOT on the trail of any new info.

http://www.universetoday.com/49440/new-pulsar-clocks-will-aid-gravitational-wave-detection/

http://www.universetoday.com/87529/astronomy-without-a-telescope-gravitational-waves/

http://www.universetoday.com/8128/the-hunt-for-gravity-waves/

http://www.universetoday.com/8219/podcast-see-the-universe-with-gravity-eyes/