Microgravity — or “zero-g” as it’s sometimes called — is not a natural state for the human body to live in for prolonged periods of time. But that is what today’s astronauts are often expected to do, whether while on expedition aboard Space Station or during a future voyage to the Moon or Mars. A host of physical issues can result from the space environment, from bone loss and muscle atrophy to the risks associated from increased exposure to radiation.

Now, there’s another downside to long-term life in orbit: eye and brain damage.

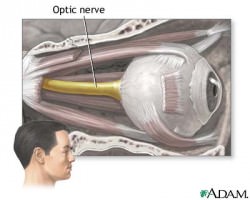

A team of radiologists led by Dr. Larry A. Kramer from The University of Texas Medical School at Houston performed MRIs on 27 astronauts, measuring in each the shape and thickness of the rear of the eyes, optic nerve, optic nerve sheath and pituitary gland.

In 7 of the 27 astronauts flattening of the backs of the eyes was noted, and enlargement of the optic nerve was detected in nearly all of them — 26 out of 27.

In addition, four exhibited deformation of the pituitary gland.

The changes to the eyes and optic nerves are similar to what are typically seen in those suffering from idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH), a disorder characterized by increased pressure within the skull. Symptoms typically include headache, dizziness and nausea, and if left untreated it can produce permanent vision loss through optic nerve damage.

“The MRI findings revealed various combinations of abnormalities following both short- and long-term cumulative exposure to microgravity also seen with idiopathic intracranial hypertension,” said Dr. Kramer. “Microgravity-induced intracranial hypertension represents a hypothetical risk factor and a potential limitation to long-duration space travel.”

Chief of flight medicine at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, Dr. William J. Tarver, noted that although no astronaut has been kept from flight duties as a result of such risks, NASA will continue to “closely monitor the situation” and has placed the potential danger “high on its list of human risks.”

The team’s paper was accepted into the journal Radiology on Feb. 1.

“Orbital and Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: Findings at 3-T MR Imaging.” Collaborating with Dr. Kramer were Ashot Sargsyan, M.D., Khader M. Hasan, Ph.D., James D. Polk, D.O., and Douglas R. Hamilton, M.D., Ph.D.

Update Oct. 24, 2013: Further investigation by researchers at Houston Methodist and Johnson Space Center have shown more evidence of long-term eye damage after just two weeks in orbit. Read more.

Goes to show we still have a lot to overcome to live and work in space. Hopefully this’ll spur development of an artificial gravity habitat, like a tethered module swinging around a counterweight – I’d love to see that in my lifetime.

Yeah, I’m not sure why we haven’t built a centrifuge for sleeping or at least a jogging track whereby an astronaut’s own forward motion could induce a feeling of weight. I wouldn’t want to be more than a week without my aunty grav.

We do need to do some studies in artificial gravity. We have yet to learn if a space station that spins for gravity will work fine or if it will make the astronauts throw up.

I don’t think a jogging track would do it – the health problems caused by weightlessness call for more than just a few minutes a day in a gravity environment. Centrifuges (of whatever design) are definitely the way forward.

… and the lesson is — … don’t just play Slim Whitman’s “Indian Love Call” in microgravity either!

Maybe earth has never been visited by advanced aliens, because their complex biochemistry would require medical healing from ever more unknown damages during long trips. So much for the theory that suspended animation would keep astronauts alive for a long journey.