Image credit: NASA

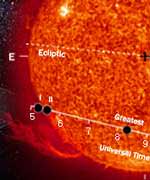

NASA invites you to safely view a rare celestial event, one not seen before by any person alive. On June 8, Venus will appear to cross in front of the sun as viewed from Earth. The last “Venus transit” occurred in 1882. The next two Venus transits are on June 6, 2012, and Dec. 11, 2117.

NASA has formed partnerships with observatories, museums, and amateur astronomers to help people safely observe the event. Special precautions are necessary to safely observe the sun. NASA’s Office of Space Science is offering exciting activities and resources for classrooms and museums. Information, resources, opportunities for educational participation, local events and viewing times, are available on the Internet at:

http://sunearthday.nasa.gov

The event may be safely observed over the Internet with images from solar observatories and satellites. For Internet viewing options, including a live webcast from Athens, Greece, made in partnership with the Exploratorium in San Francisco, Calif., visit:

Centennial Challenges Workshops

The Venus transit will be visible from approximately 75 percent of the Earth. For a map of the transit visibility on the Internet, visit:

http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/transit/TV2004/TV2004-Map1b.GIF

Transit times for cities worldwide are available on the Internet at:

http://sunearth.gsfc.nasa.gov/eclipse/transit/TV2004.html

“People using a filter approved for safe solar viewing can expect to see a small black dot, about 1/30 the size of the solar disk, very slowly moving across the sun,” said Fred Espenak, an eclipse expert at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

During the 19th century, Venus transits were essential for astronomers to determine the scale of the heavens. Transits were used to calculate a relatively accurate distance from the Earth to the sun. Once that distance was determined, astronomers calculated the size of our solar system. They also calculated distances to nearby stars by measuring how much they appeared to shift against remote background stars, as the Earth progressed in its orbit around the sun.

So critical was this measurement that, beginning in 1761, leading nations sent expeditions to remote corners of the globe to exactly time when Venus appeared to begin its transit of the sun. The precise timing of the transit depended on location, because different places on the Earth observed the event from different angles. The times were compared, and the distance to the sun calculated using the known distances between expedition locations on the Earth and trigonometry.

The transit phenomenon also has relevance for the future of astronomy. Scientists with NASA’s Kepler mission hope to discover Earth-like planets outside our solar system by searching for transits of other stars by planets that might be orbiting them.

NASA’s Kepler mission is scheduled for launch in October 2007. It will allow astronomers to find planets, perhaps the size of Earth, orbiting other stars by looking for tiny dips in the brightness of a star when a planet crosses in front of it. Periodic brightness dips will signal the presence of a planet in orbit around the star, even if the planet is not directly visible. For information about the Kepler mission on the Internet, visit: