Peer at this new image of Mars’ Ladon Basin and you get some notion of the violence that took place during the early history of Mars.

ESA’s Mars Express imaged the southern part of the partially buried crater informally known as Ladon Basin. The basin is the site of an ancient impact which is about 440 kilometers (273 miles) across. On an earthly scale, Ladon Basin would stretch from London to Paris or fill up most of Colorado.

These zoomable images allows you to quickly zoom into whatever part of the picture you want to see close up. Just slide the scale (between the plus and minus sign) at the bottom of the application to zoom in.

Large-scale evidence of water draws scientists to explore this area of Mars. With signs of ancient lakes and rivers, NASA considered nearby Holden and Eberswalde craters as possible landing sites for the Mars Science Laboratory, or Curiosity. The car-sized rover is now slated to land in Gale Crater on August 6.

The most stunning part of this image are the interconnected craters Sigli and Shambe. Elliptical craters like these form when asteroids or comets smack into the surface of planets and moons at a shallow angle. A fluid-like ejecta pattern surrounds the craters suggesting that subsurface ice melted during the impact. Other smaller craters can be seen dotting this blanket of material.

3D Perspective: This computer-generated perspective view was created using data obtained from the High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) on ESA’s Mars Express. Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum). Zoomify by John Williams.

Explore the deeply fractured floor of the twin craters to the left in the image. Scientists believe both craters formed when a large meteorite splintered into two chunks just before impact. The joined craters then filled with sediment. Fractures also extend outside the image in concentric rings.

Throughout the image, a distant echo of water is etched in the now dry landscape. Above the connected craters, to the west in this image, creek-like channels can be seen leading into the nearby impact basin to the right (or north) indicating that in Mars’ distant past, water flowed across this landscape. Instruments aboard Mars Express and other Mars orbiters have detected clay minerals within deposits in and around Ladon Basin. These deposits suggest a relatively long presence of liquid water in the region’s past.

To get a different perspective, grab your red/blue 3D glasses and zoom into the image below.

Anaglyph: Ladon Valles imaged during revolution 10602 on 27 April 2012 by ESA’s Mars Express using the High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC). Data from HRSC’s nadir channel and one stereo channel are combined to produce this anaglyph 3D image that can be viewed using stereoscopic glasses with red–green or red–blue filters. Credits: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin (G. Neukum). Zoomify by John Williams.

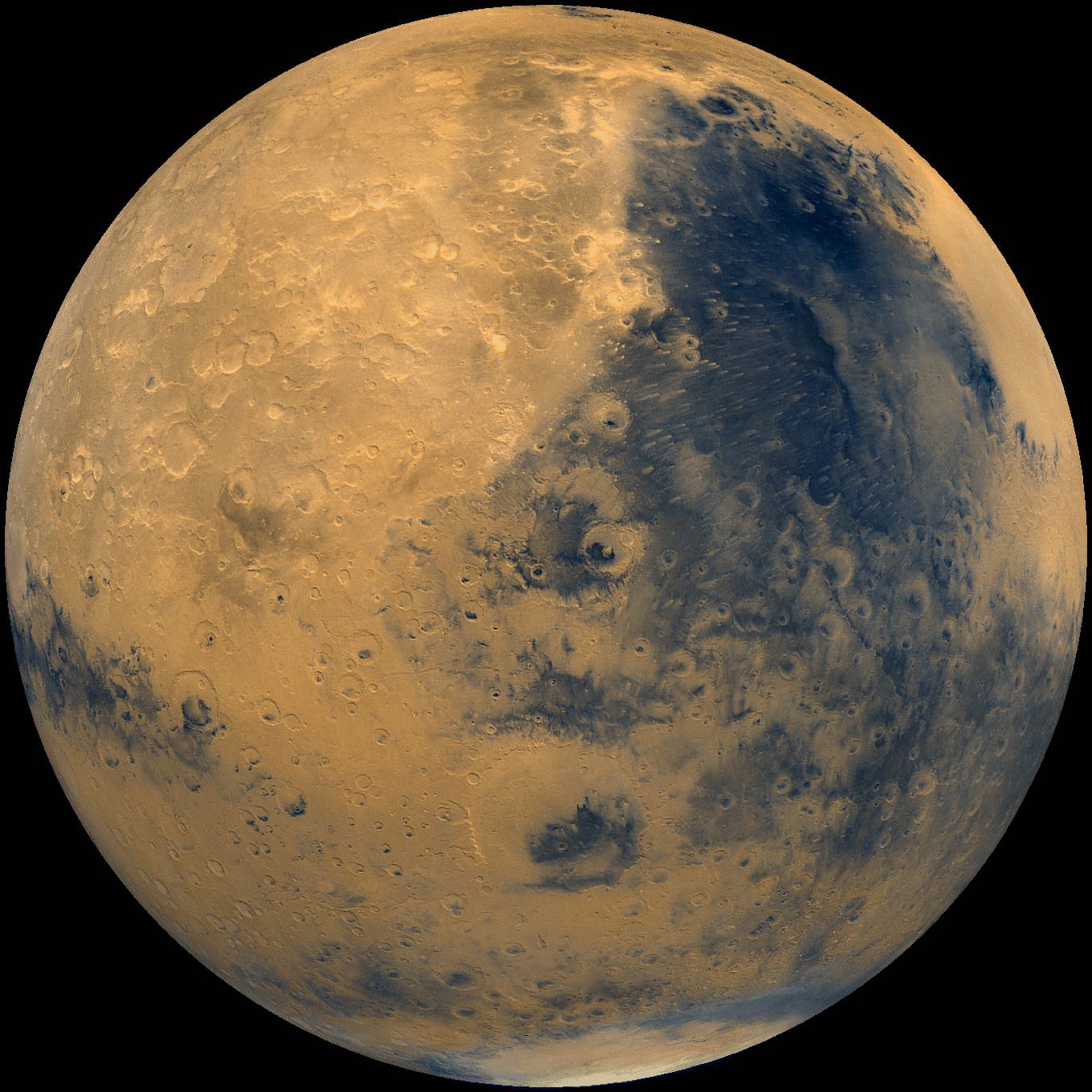

Lead image Caption: High-Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) nadir and colour channel data taken during revolution 10602 on 27 April 2012 by ESA’s Mars Express have been combined to form a natural-colour view of the Ladon Valles region. Centred at around 18°S and 329°E, this image has a ground resolution of about 20 m per pixel. Zoomify by John Williams.

John Williams is a science writer and owner of TerraZoom, a Colorado-based web development shop specializing in web mapping and online image zooms. He also writes the award-winning blog, StarryCritters, an interactive site devoted to looking at images from NASA’s Great Observatories and other sources in a different way. A former contributing editor for Final Frontier, his work has appeared in the Planetary Society Blog, Air & Space Smithsonian, Astronomy, Earth, MX Developer’s Journal, The Kansas City Star and many other newspapers and magazines.

Looking at statistics of fracturing could perhaps give a clue on how dense the early atmosphere was.

But isn’t it an elliptical feature by superposition?

You need same fairly flat trajectories to make hypervelocity craters elliptical since they deposit so much energy. Typically the radius of an impactor is 1/20 of the radius of the impact scar.

And the short relatively short distance between the centers of impactors makes a more vertical impact likelier.

[Disclaimer: I’m just hand waving here, haven’t actually tried to extract data from the figures.]

Maybe its a caldera?

The double feature makes it unlikely. A fractured impactor fits.

Check out Yellowstone Caldera outline for reference of “unlikely”.

I looked a bit better at the image and noted the following:

– Heavy fracturing North West, might indicate impact causing a trapped gas release and collopse of the Western Half of a gas trap.

– A compression hill in center just east of the main center fracture line running north south, most probably pointing to a sliding of the East half against the West half … fitting a Western collapse followed by an Eastern collapse. A secondary compression hill can be found further down south.

– West, indication of plate being pushed into wall with a wall collapse onto the western half of the plate

– Indication of a regolith runoff in North Eastern part into a gully

– Formation of a gully in the north eastern part indicating two hills

Just as important is what is missing …

– No Regolith desplacement worth the missing volume

– No central peak due to backdraft pressure (think mushroom cloud on impact with central pillar being created by pressure rather than heat)

To me, odds of that being an impact crater is … null.

Very nice ‘zoomable’ graphics. But… I have to wonder, after using my red/blue viewer on that last 3-D image, if the verticle scale has been exaggerated, If so, and it is common in other photos I’ve seen, it is a scientific crime not to say so. Maybe it actually looks like that as, unlikely as it seems, with some of the cliffs apparently overhanging the floor of the crater.

A “…scientific crime…”? And who might that criminal be? ESA for not making that info. easy to find in their Mars Express webpage? Universe Today for not providing that info.? Or the viewer for not spending the time to find out himself? Regardless, an interesting question… I think I’ll poke around a bit and see what I can find out for you….

Ok, maybe ‘scientific crime’ was an overstatement. But it is a pet peeve of mine. Any time images are presented to the public, by ESA, by UT, or anyone else it should be said if they’ve been manipulated. Strectched, compressed, color enhanced, whatever. People see these images and think that is would the human eye would see. If not a crime, it is certainly a disservice.

Recently I was part of a group of tourists at McDonald Observatory who got a chance to look through the 86″ telescope, to look at distant galaxy. I loved it because it was real but most everyone else was dissapointed because it didn’t look like a highly enhanced Hubble photo. Hubble photos are beautiful, and informative, but they are not what the human eye would see.

And I think every photo I’ve seen of Valis Marinaris has the verticle scale eggagerated for ‘dramatic effect’.

And every depiction of the asteroid belt show this crowded, jumbled, bunch of rocks when in fact if you were on asteroid you could not see another except, maybe, as a distant point of light.

Lying by omission, and failure to disclose manipulation, *is* not good because it distorts reality without most people realizing they’re being decieved.