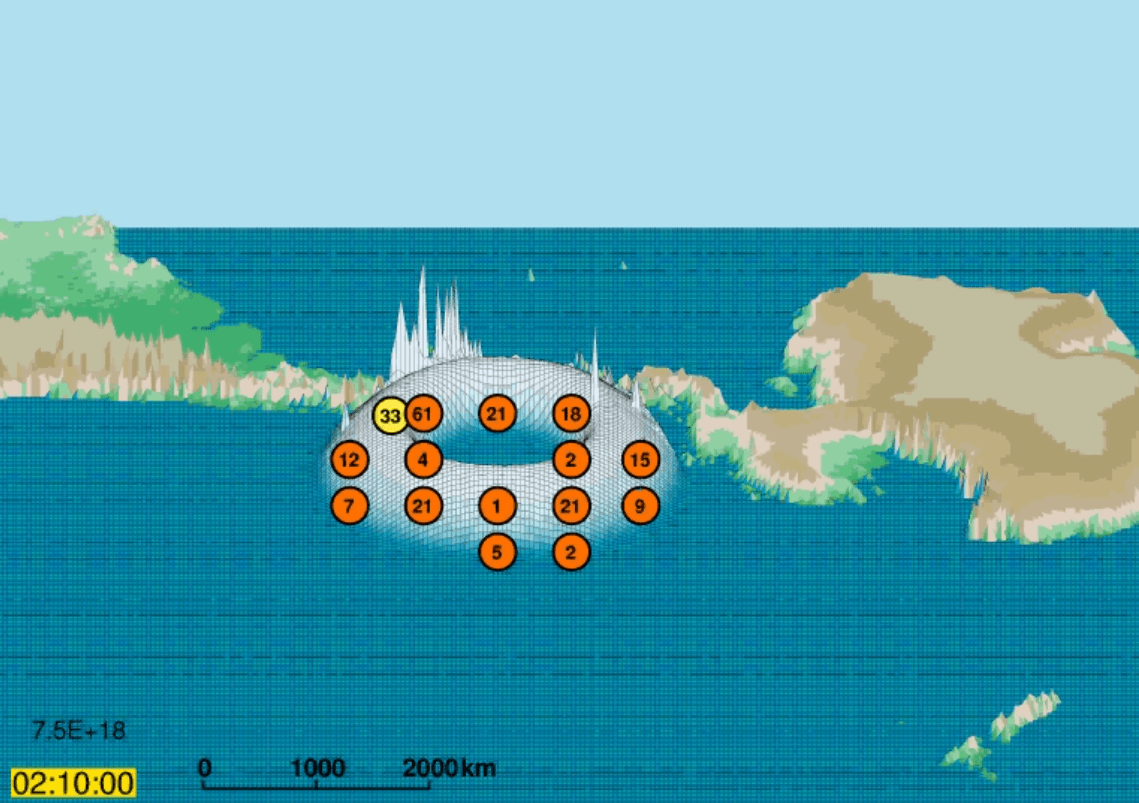

A simulation of the Eltanin meteor strike

When a mountain-sized asteroid struck the deep ocean off the coast of Antarctica 2.5 million years ago, it set off an apocalyptic chain of events: a devastating rain of molten rock and then a deadly tsunami that inundated the coastlines of the Pacific Ocean. But according to a team of Australian researchers, this was just the beginning. Then came a protracted ice age that killed off many of the Earth’s large mammals.

The Eltanin meteor, named after the USNS Eltanin which surveyed the area in 1964, is the only impact that has ever been discovered in a deep-ocean basin. These deep water impacts must be more common – so much of the planet is ocean – but they’re tricky to find because of the inaccessible depths of the impact craters. Researchers examining sediments in the area discovered tiny grains of impact melt and debris from meteorite fragments. Something big smashed this spot.

An asteroid strike on land is devastating, but an asteroid strike in the deep ocean is even worse. On both land and ocean, you get the plume of water vapor, sulfur, and dust blasted into the high atmosphere, raining molten rock down across a wide area. But for asteroid strikes in the ocean, this is followed by a devastating tsunami that inundates coastlines around the world. There are waves hundreds of meters high at the crash site, and they travel deep inland on every coastline. A local event becomes a global event.

But with the Eltanin meteor, this was followed by a prolonged ice age.

Professor James Goff and his colleagues from the University of New South Wales in Australia have been researching the Eltanin meteor and its after-effects. The timing of the impact seems to line up with geologic deposits in Chile, Australia and Antarctica. Geologists traditionally connected these deposits with slower geological processes, like glaciation. But Goff and his team think these deposits might have been dropped all at once by the devastating tsunami from Eltanin.

Here’s a video that shows how the impact and subsequent tsunami might have played out.

Although the Earth was already thought to be cooling in the mid to late Pliocene, the material kicked into the high atmosphere by Eltanin could have pushed the planet’s climate past the tipping point:

“There’s no doubt the world was already cooling through the mid and late Pliocene,” says co-author Professor Mike Archer. “What we’re suggesting is that the Eltanin impact may have rammed this slow-moving change forward in an instant – hurtling the world into the cycle of glaciations that characterized the next 2.5 million years and triggered our own evolution as a species.”

It was this time of a global ice age that transitioned the planet from the Pliocene to the Pleistocene. It was a bad time to be a Chalicothere or Anthracotheriidae, but a good time to be a hominid. So… thanks Eltanin.

View Larger Map

The location of the Elatin meteor crater

Original Source: Journal of Quaternary Science

I’ve always wondered if it would be possible for current society to move on from an event such as this – if it where to happen within our lifetime… Economies would halt, there would be mass fear, countries would be wiped out, and there would be an incredible loss of life.. I suspect us survivors would all be living on cans of baked beans for a while.

Notice the fault lines near the impact site… ‘X’ marks the spot! Other ‘X’ spots might be… the Peugeot Sound? or Hudson’s Bay? Hmmm…..

That isn’t what is going on though. If you zoom out you will note that the impact is in an old inactive zone well within the Antarctic plate, and that the ocean crust is riddled with old and new faults. So the likelihood for a correlation is too high to be remarkable.

The reason for the density of scars is that the ocean plates are ductile and move from midoceanic ridges outwards. Then correlating scars with impacts is an unmotivated pattern search.

Plate tectonics is not driven by impactors. Then impactor influence is unlikely. Ridges would be hoof beats and mantle convection horses, while impactors are zebras.

For example here, the Eltannin impactor was ~ 1 km, leaving the 20 times larger 20 km crustal scar that has been found. The oceanic plates are ~ 100 km thick, as they consist of a thin crust and the sufficiently non-fluid and thick litosphere. The impactor wasn’t thick enough to punch through.

Even if something like a hotspot flow punch through a thin plate section, they don’t always force a plate rift. See the Hawaiian hotspot (I think).

What I’m suggesting is that a large enough impact may be compared to cutting glass? Concentrated shock waves, due to the density of water, might spread the effects of that impact where the crust is thinner – such as in the ocean basins. I suspect that if we look closely enough, evidence of ancient impacts will be found at many plate intersections in the Earth’s crust.

Just a quick point, it’s UNSW, not USNW

Interesting news item. I mentioned it on my twitter account: twitter.com/GirlForScience.

If anyone is interested, I tweet about fun science news. Please follow 🙂

That is certainly one hypothesis. But on anthropology we outsiders must be aware that the difficult field has nurtured schools belonging to major divisive hypothesis like out-of-Africa vs multiregionalism.

Here is a relatively recent (2010) review of the climate-as-evolutionary-driver hypothesis on human evolution:

“The explanations that we’ve had tied human origins back to an African savannah or to a European ice age,” Potts says, “and it was never really adequate to understand the plasticity, the versatility of the human species.”

“Which raises a question, Potts says: “Not how did humans become adapted to a specific ancestral environment, but how did we become adaptable?” Extraordinarily adaptable to so many different environments.”

That was perhaps more urgent with the old out-of-Africa hypothesis, which looked like an explosion with a ready toolbox of adaptive traits and technologies. With DNA showing several migrations, including possibly failed ones, the constraints on adaptability may become less severe.

An interesting and timely question, in other words.