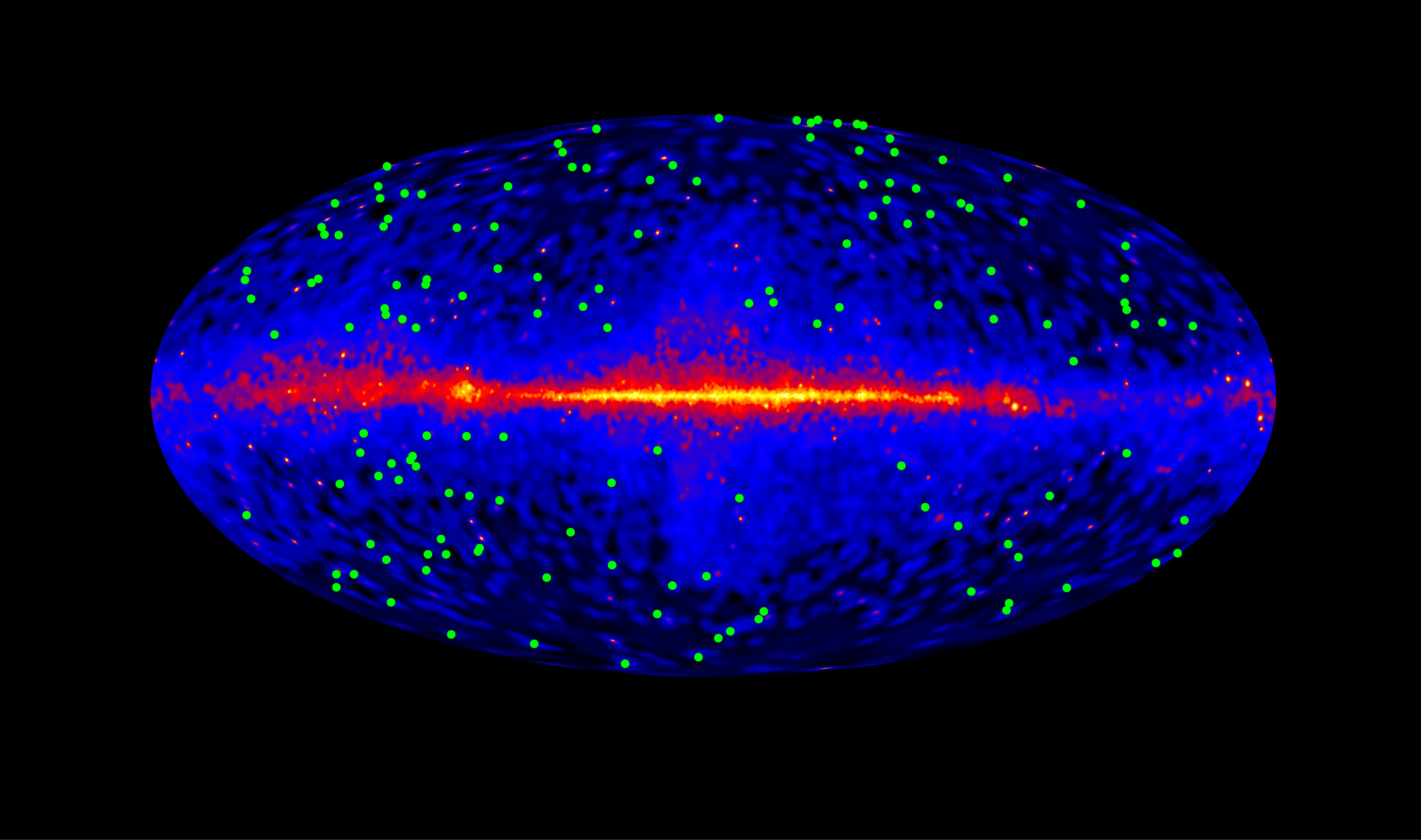

This plot shows the locations of 150 blazars (green dots) used in the a new by the Fermi Gamma-Ray Telescope. Credit: NASA/DOE/Fermi LAT Collaboration

All the light that has been produced by every star that has ever existed is still out there, but “seeing” it and measuring it precisely is extremely difficult. Now, astronomers using data from NASA’s Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope were able to look at distant blazars to help measure the background light from all the stars that are shining now and ever were. This enabled the most accurate measurement of starlight throughout the universe, which in turn helps establish limits on the total number of stars that have ever shone.

“The optical and ultraviolet light from stars continues to travel throughout the universe even after the stars cease to shine, and this creates a fossil radiation field we can explore using gamma rays from distant sources,” said lead scientist Marco Ajello from the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology at Stanford University in California and the Space Sciences Laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley.

Their results also provide a stellar density in the cosmos of about 1.4 stars per 100 billion cubic light-years, which means the average distance between stars in the universe is about 4,150 light-years.

The total sum of starlight in the cosmos is called the extragalactic background light (EBL), and Ajello and his team investigated the EBL by studying gamma rays from 150 blazars, which are among the most energetic phenomena in the universe. They are galaxies powered by extremely energetic black holes: they have energies greater than 3 billion electron volts (GeV), or more than a billion times the energy of visible light.

The astronomers used four years of Fermi data on gamma rays with energies above 10 billion electron volts (GeV), and the Fermi Large Area Telescope (LAT) instrument is the first to detect more than 500 sources in this energy range.

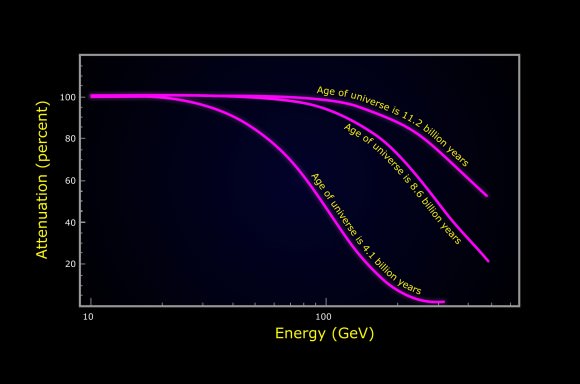

To gamma rays, the EBL functions as a kind of cosmic fog, but Fermi measured the amount of gamma-ray absorption in blazar spectra produced by ultraviolet and visible starlight at three different epochs in the history of the universe.

Fermi measured the amount of gamma-ray absorption in blazar spectra produced by ultraviolet and visible starlight at three different epochs in the history of the universe. (Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center)

“With more than a thousand detected so far, blazars are the most common sources detected by Fermi, but gamma rays at these energies are few and far between, which is why it took four years of data to make this analysis,” said team member Justin Finke, an astrophysicist at the Naval Research Laboratory in Washington.

Gamma rays produced in blazar jets travel across billions of light-years to Earth. During their journey, the gamma rays pass through an increasing fog of visible and ultraviolet light emitted by stars that formed throughout the history of the universe.

Occasionally, a gamma ray collides with starlight and transforms into a pair of particles — an electron and its antimatter counterpart, a positron. Once this occurs, the gamma ray light is lost. In effect, the process dampens the gamma ray signal in much the same way as fog dims a distant lighthouse.

From studies of nearby blazars, scientists have determined how many gamma rays should be emitted at different energies. More distant blazars show fewer gamma rays at higher energies — especially above 25 GeV — thanks to absorption by the cosmic fog.

The researchers then determined the average gamma-ray attenuation across three distance ranges: The closest group was from when the universe was 11.2 years old, a middle group of when the Universe was 8.6 billion years old, and the farthest group from when the Universe was 4.1 billion years old.

This animation tracks several gamma rays through space and time, from their emission in the jet of a distant blazar to their arrival in Fermi’s Large Area Telescope (LAT). During their journey, the number of randomly moving ultraviolet and optical photons (blue) increases as more and more stars are born in the universe. Eventually, one of the gamma rays encounters a photon of starlight and the gamma ray transforms into an electron and a positron. The remaining gamma-ray photons arrive at Fermi, interact with tungsten plates in the LAT, and produce the electrons and positrons whose paths through the detector allows astronomers to backtrack the gamma rays to their source.

From this measurement, the scientists were able to estimate the fog’s thickness.

“These results give you both an upper and lower limit on the amount of light in the Universe and the amount of stars that have formed,” said Finke during a press briefing today. “Previous estimates have only been an upper limit.”

And the upper and lower limits are very close to each other, said Volker Bromm, an astronomer at the University of Texas, Austin, who commented on the findings. “The Fermi result opens up the exciting possibility of constraining the earliest period of cosmic star formation, thus setting the stage for NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope,” he said. “In simple terms, Fermi is providing us with a shadow image of the first stars, whereas Webb will directly detect them.”

Measuring the extragalactic background light was one of the primary mission goals for Fermi, and Ajello said the findings are crucial for helping to answer a number of big questions in cosmology.

A paper describing the findings was published Thursday on Science Express.

Source: NASA

could space-time slow down [light/particles](different energy forms) over long distances since we know there is a ‘frame dragging’ phenomena?

🙂

I have always wondered how relativity factors into the measurement of time on such scales.

I’m glad to see you mention ‘frame dragging’. From the first time I heard of the ‘gravity B’ probe I’ve been fascinated by concept. Our experiments here have only been concerned with the gravity field in near earth space but might the whole galaxy be dragging space around it? Maybe this has implications for theories about dark energy and dark matter?

I thought some stars were completely undetectable due to the expansion rate of the universe due to dark energy.

these blazars are not that far away, as this article states

“All the light that has been produced by every star that has ever existed is still out there”

I can’t agree with that statement. All the light that I have seen from every star that ever existed was absorbed by my retina and is no longer ‘out there’.

Agreed – suspect enthusiasm resulted in “All the light” instead of “Some proportion of the light” being used!

I also agree with Micah – in the context of the above “All the light”…”produced by every star” quote – many stars in scope would be beyond our visible horizon – as they are too distant for their light to have reached us.

~ “Their results also provide a stellar density in the cosmos of about 1.4 stars per 100 billion cubic light-years, which means the average distance between stars in the universe is about 4,150 light-years.”

“1.4 stars per 100 billion (with a B) cubic light years”?! From past inflation to the present of local Time, and yet even more into future expansion of Space, a lot of empty, unused (but, no doubt, not useless) real-estate exists out there in the dark fields of heaven! _______________________________________________________

~ “All the light that has been produced by every star that has ever existed is still out there” ~

It appears the poets had it right, in evening verse of eternal starlight.

It is probably best to say this is a record of every star that is on our past light cone.

LC

So,once we gather all of this information on how much light exists, what do we do with the data. ????

“The Fermi result opens up the exciting possibility of constraining the earliest period of cosmic star formation,”.

That period is more or less completely unknown (even unconstrained) at the moment.