Whitewater Lake is the large flat rock in the top half of the image. From left to right it is about 30 inches (0.8 meter) across. The dark blue nubby rock to the lower left is “Kirkwood,” which bears non-hematite spherules. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ Cornell Univ./Arizona State Univ.

Steve Squyres, Principal Investigator for the Mars Explorations Rovers, cracked open the equivalent of the Opportunity rover’s field geologist’s notebook to describe what he called “a delightful geological puzzle.”

“This is a work in progress,” Squyres said at the American Geophsical Union conference today, “But this is our first glimpse ever at conditions on ancient Mars that clearly show us a chemistry that would have been suitable for life.”

While both the MER rovers have found evidence of past water on Mars, all indications are that it would have been very acidic, with “battery-acid kind of numbers making it very challenging for life,” Squyres said.

Newly found clays that are sprinkled with two different kinds of previously unseen features point to a different type of water “that you could drink,” Sqyures added.

Orbital data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s CRISM (Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars) instrument originally led the MER team to Endeavour Crater, the huge crater where Opportunity is now traversing around the rim.

“It was discovered from CRISM that there were clay minerals there,” Squyres said, “and clays form in a watery environment, and only form under a neutral pH, water that is not acidic.”

The rover has found a region filled with light-toned rocks, such as the Whitewater Lake rock, above, around a small hill named “Matijevic Hill” in the “Cape York” segment of the rim of Endeavour Crater. Squyres described it as the “sweet spot” where clays are known to be present.

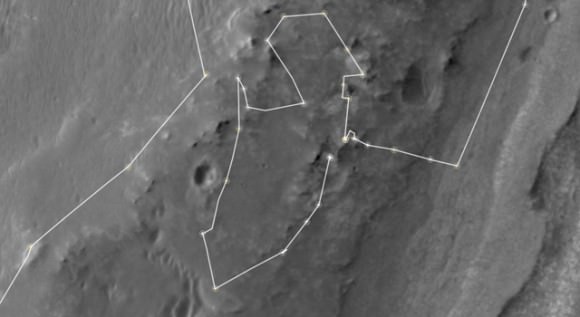

This map shows the route driven by NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity during a reconnaissance circuit around an area of interest called “Matijevic Hill” on the rim of a large crater. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

They have since driven the rover around Matijevic Hill to survey the clays, “which is what you would do if you were a geologist at a site, you’d walk the outcrop,” Squyres said. “We’ve got a good map of where the good, interesting stuff is at Matijevic Hill.”

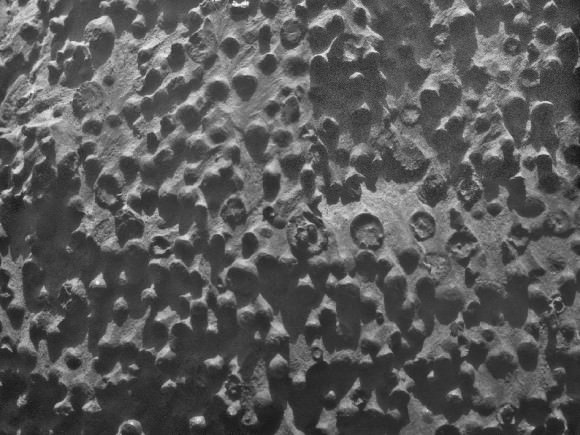

Interspersed on the light-toned rocks are fine veins of even lighter material, which has never been seen before. Additionally, there are “fins” of darker rock sticking up in the region, and within the fins are dense concentrations of spherical little features, about 3 mm in size that are very similar to the hematite Martian “blueberries” that Opportunity has seen before. But when they looked at the chemical composition of these spheres, the science team found they weren’t blueberries, because they contained no iron, which is what hematite is made from.

“It’s something totally different, and I’ve started calling them ‘newberries’,” said Squyres.

Small spherical objects fill the field in this mosaic combining four images from the Microscopic Imager on NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Cornell Univ./ USGS/Modesto Junior College

It is difficult for the rover to determine the chemical make-up of the newberries and the light-colored veins because they are such small features, the rover can’t focus merely on those features. But Squyres and team have come up with a to-do list to try and figure out the mystery of the clays and newberries:

Task one is to understand the Whitewater Lake rock better and look at the rock’s sediments, to understand the layers in the rock: were the layers laid down by water, impact or another process?

The second task is to figure out what the newberries made of. They will have to observe regions that have different concentrations of the spherules to eke out what minerals are and aren’t part of the newberries.

Task three is to find a “contact place” where the light-toned clay rocks like Whitewater are touching the breccias – the broken and fused rock born of the impact that created the crater – that is present all around the rim of Endeavour. They haven’t yet found a place where the two are together.

Task four is to figure out what the fine veins are in the clay rocks.

The tasks are intertwined, Squyres said. “Figuring out the newberries will be important for figuring out the how these clays were laid down. So the stories aren’t independent, they are woven together and we still have homework to do,” he said.

But the team will have to work fast.

Opportunity image of light, flat rocks containing clay and mysterious darker rocks jutting through them. NASA/JPL-Caltech/ Cornell Univ./Arizona State Univ

They have about 6 months before winter sets in again in Meridiani Planum on Mars.

“We’ll soon start doing some serious winter planning,” said Diana Blaney, Deputy Project Scientist. When asked about the potential for Oppy to make it through another winter, Blaney said it all depends on the amount of dust build-up on the solar panels and how much power can be generated. “We don’t have any reason not to expect to survive, but it is a dynamic situation, and are looking ahead to find potential wintering sites,” that have beneficial tilt for the rover to absorb as much sunlight as possible.

The last winter the Opportunity rover endured was the first time the rover had to remain stationary due to power concerns because of dust accumulation on the solar arrays.

“We’re nine years into a 90 day mission,” Squyres said, “and every day is a gift at this point and we’re just going to keep pushing ourselves and the rover.”

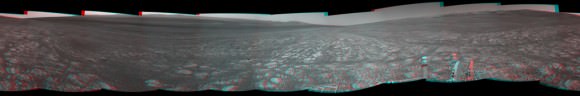

A 3-D mosaic of the Cape York region where Opportunity is now working. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ Cornell Univ./Arizona State Univ

For additional information, see this NASA press release.

I miss Spirit…

It’s great to hear from the ole’ Oppy team, again!

NASA really should make joint Opportunity&Curiosity Updates on their YouTube channel!

Go Oppy! Curiosity is, rightly, all the buzz these days, but this sturdy little guy is still producing excellent science and making huge discoveries.

Ok, if they’re finding different kinds of berries on Mars, there’s at least plant life there (jk)!

Good to see that Oppy’s big brother isn’t getting all of the attention.

Past non-acidic conditions are of course great for habitability, as is current ones like Phoenix found:

“Results published in the journal Science after the mission ended reported that chloride, bicarbonate, magnesium, sodium potassium, calcium, and possibly sulfate were detected in the samples. The pH was narrowed down to 7.7±0.5.”

Why does the ground look wet in this picture? Isn’t that water puddled around the big rock? Or should we get a bigger picture?