Just about any space mission these days requires water training. Think of the countless hours astronauts spend in the Neutral Buoyancy Laboratory at the Johnson Space Center, practicing the steps to do spacewalks. Then there are the crews that actually live in the ocean for days at a time on NASA’s NEEMO missions.

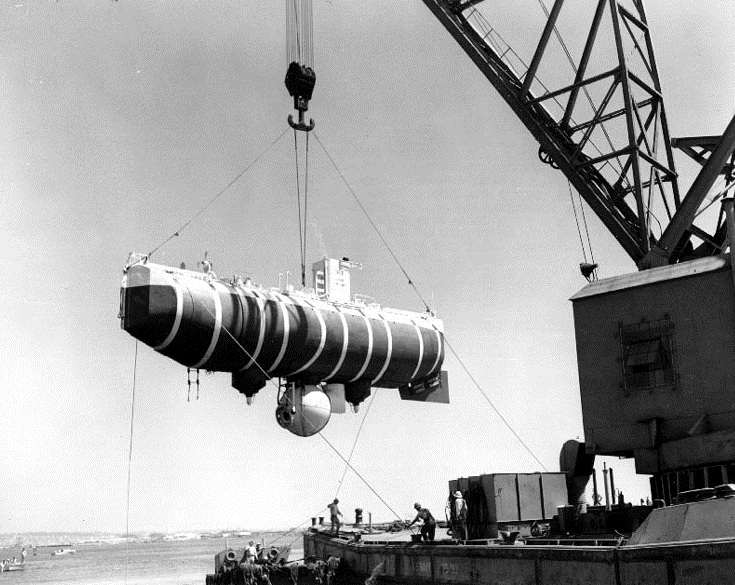

Long before these “aquanauts” added flippers to their list of equipment, however, the U.S. Navy was busy exploring the depths of the ocean. Today – Jan. 23 – marks the anniversary of the Bathyscaphe Trieste’s descent to the bottom of the ocean in 1960. This was the first time a vessel, manned or unmanned, had reached the deepest known point of the Earth’s oceans, the Mariana Trench.

Trieste was at first operated by the French Navy, which operated it for several years in the Mediterranean Sea, but the US Navy purchased the Trieste in 1958.

Although two men took the ride down, all accounts say that it was an isolating experience. Jacques Piccard – well-known today for his exploration of the oceans – and US Navy Lieutenant Don Walsh descended about 11 kilometers (7 miles) to the bottom.

Fighting with poor communications and high pressure – which cracked a window at 30,000 feet below the surface – the crew made their way to ocean floor. They worked in a tiny sphere only 2 meters (6.5 feet) wide, and according to the University of Delaware, the interior reached frigid temperatures of 7 degrees Celsius (45 degrees Fahrenheit) during their successful descent and return.

Spaceflight and deep-ocean diving share many similarities, as this mission demonstrated. The early days of the space program had communications blackouts as spaceships flew between stations; this proved to be a near-disaster for the Gemini 8 crew in 1966 when their spacecraft spun out of control during a period with no voice connection to the ground.

Also, sustaining life is no less challenging in the water as it is in space. Humans require oxygen, pressure and a comfortable environment where they work. Crews in space have faced serious problems with all of these matters before – Mir suffered a partial depressurization in 1997, and the early days of the Skylab space station were rather hot until the astronauts could deploy a sunshade.

Walsh was not available for an interview with Universe Today due to travel, but in a 2012 BBC interview he noted that he had reserved confidence that they would make it to the bottom.

“I knew the machine well enough, at that point, to know that theoretically, it could be done,” Walsh recalled.

The mens’ feat would go unrepeated for decades, until in 2012 Hollywood director James Cameron made the descent again – alone, although certainly equipped with more modern technology. For comparison, only one American has flown solo in space since the 1960s; in 2004, Mike Melvill piloted SpaceShipOne into suborbital space twice as part of the Ansari X-Prize win.

Although I could be wrong, from what I have heard about metallurgy, the stresses placed on that steel sphere from that descent were such that its molecular and crystaline characteristics were thought to be altered irreversibly. Perhaps that is one of the reasons that that was the bathyscaphe’s last dive. I saw the Trieste on the dock in San Diego a

few years after the dive during my Navy days.

Mike Melvill did pilot SS1 above 100kms twice but Brian Binnie piloted the second SS1 X-Prize flight.

Is the Trieste in a museum now ?