Many sci-fi plots revolve around alien life reaching Earth and causing problems. In "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," alien pods arrive on Earth and replace humans. In "The Thing," a shape-shifting alien creature takes over an Antarctic research base and begins killing people. While frightening and titillating, these are easily dismissed as highly unlikely.

However, in "Life," a single-celled alien life form arrives in a Mars sample and rapidly evolves into a dangerous hostile creature. While rapid evolution seems unlikely, the premise isn't far-fetched: Mars samples could host microbial life and must be handled carefully.

A mission will likely return Martian samples to Earth in the next decade or so. Scientists hope that those samples will provide conclusive evidence of life on Mars when they arrive. But what if the samples contain actual, extant life? It could be disastrous if Martian life came into contact with Earth.

That's why we need to be sure if anything is alive in those samples. A team of researchers are developing stringent techniques to scan these samples and determine if they contain anything living.

Their method is presented in research titled "Submicron-scale detection of microbes and smectite from the interior of a Mars-analogue basalt sample by optical-photothermal infrared spectroscopy." The lead author is Yohey Suzuki, Associate Professor from the Department of Earth and Planetary Science at the University of Tokyo.

"It’s an exciting time to work in this field. It might only be a matter of years before we can finally answer one of the greatest questions ever asked." - Yohey Suzuki, University of Tokyo

"For near-future missions planned for Mars Sample Return (MSR), an international working group organized by the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR) developed the sample safety assessment framework (SSAF)," the authors explain in their paper. "To prepare for MSR, analytical instruments of high sensitivity need to be tested on effective Mars analogue materials."

The eventual Mars Sample Return mission is classified by COSPAR as a 'Category V restricted Earth return'. That means that any unsterilized samples must be kept strictly contained and subjected to only the most sensitive analytic techniques. To advance this, the sample safety assessment framework (SSAF) was developed.

"The SSAF targets living organisms, their resting states (e.g. spores, cysts), or their remains in Martian materials," Suzuki and his co-authors explain in their research. "The tentative level of safety assurance is a risk value of 1 in a million chance of failing to detect life if it is present." The only way to approach this level of assurance is to study Earthly analogues of Martian rocks.

Earth and Mars are wildly different planets in many ways, but they're similar in their bulk compositions. They share major compositional elements like oxygen, silicon, iron, and magnesium. They also share silicate minerals like olivine and clay minerals like smectites, though Earth has greater mineral complexity. This points out that finding Earthly analogues for Mars sample materials isn't an overwhelming challenge.

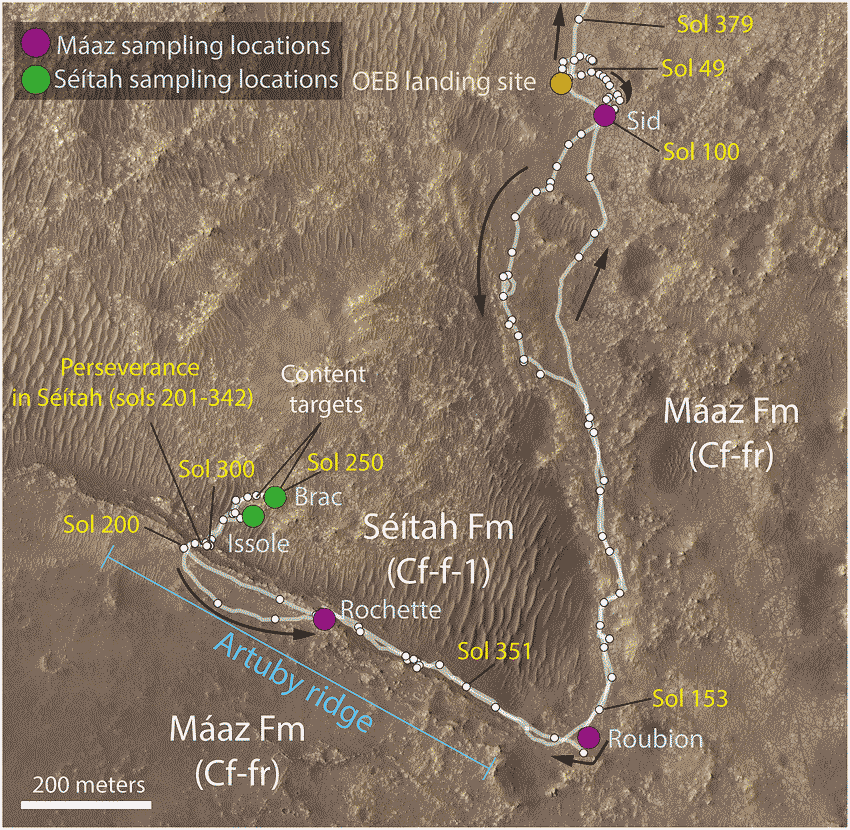

Suzuki and his colleagues chose basalt as their Mars analogue in their research. Basalt is common in both worlds and is known to host microbial life on Earth. Perseverance has already sampled basalt on the floor of the Jezero crater. "Two basalt samples with aqueous alteration cached in Jezero crater by the Perseverance rover are planned to be returned to Earth," the researchers write.

The Maaz formation on the floor of Jezero Crater is rich in basaltic lava, and the Perseverance Rover has already collected samples from the formation for return to Earth. Image Credit: Udry et al. 2023.

The Maaz formation on the floor of Jezero Crater is rich in basaltic lava, and the Perseverance Rover has already collected samples from the formation for return to Earth. Image Credit: Udry et al. 2023.

In previous research, the researchers developed techniques to examine basalt and detect microbial life. These techniques were based on nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry (NanoSIMS) and electron microscopy coupled with energy-dispersive spectroscopy. The authors write that these methods "revealed microbial colonization at clay-filled fractures." However, these methods are destructive testing methods. When your samples come from a different planet that spends most of its time almost 150 million km. away, they're not easily replaced and must be handled carefully.

In this new research, Suzuki and his co-researchers worked on non-destructive testing methods. They focused on Optical-photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectroscopy, a non-destructive technique with a higher spatial resolution. O-PTIR is a relatively new and powerful analytical technique. It exploits the fact that when a sample absorbs light, it heats up, changing its refractive qualities. As an added bonus, O-PTIR requires only minimal sample preparation.

"We first tested conventional analytical instruments, but none could detect microbial cells in the 100-million-year-old basalt rock we use as the Martian analogue. So, we had to find an instrument sensitive enough to detect microbial cells, and ideally in a nondestructive way, given the rarity of the samples we may soon see," said lead author Suzuki in a press release. "We came up with optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectroscopy, which succeeded where other techniques either lacked precision or required too much destruction of the samples."

While not ground up or otherwise destroyed in other methods, samples for O-PTIR must have their outer layers removed and be sliced into pieces only 100 μm thick. While this changes the sample, it leaves plenty of material intact and available for other analytical methods and tools, even ones that have yet to be developed. O-PTIR has a resolution of 0.5 μm, high enough to discern when a sample contains living tissue.

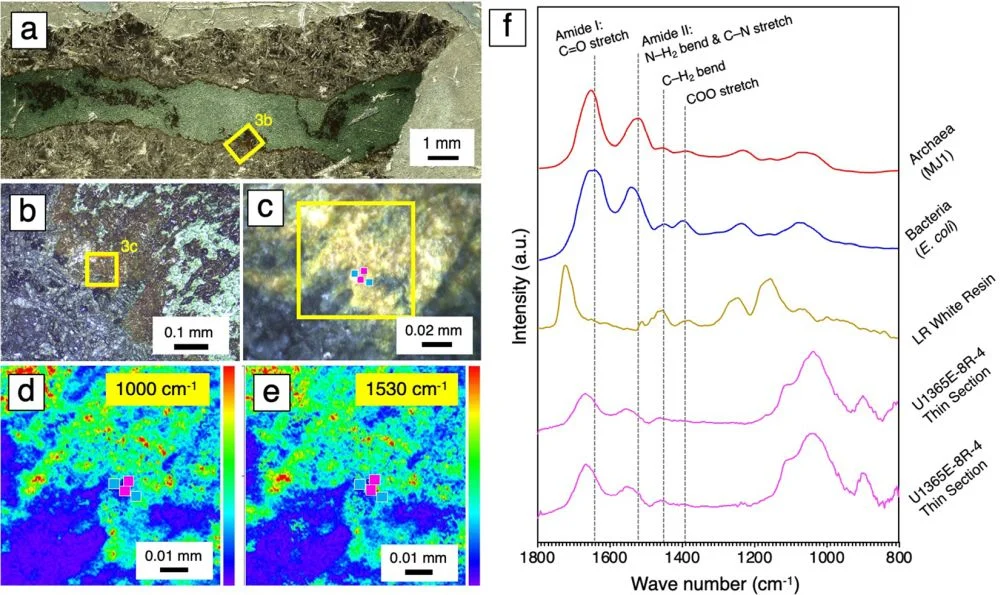

The authors report that their analysis of clay-filled fractures in Earthly basalt delivered "in-situ spectra diagnostic to microbial cells, consistent with our previously published data obtained by NanoSIMS."

These are photographs of a nontronite-bearing fracture in a thin section of the rock core interior (a–c) with increasing magnification. Pink and blue points represent the mineral smectite and peptides indicating microbial cells, respectively. d and e are Intensity maps of optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectra in a region highlighted with a yellow square in the three photographs. On the right are duplicate O-PTIR spectra of the pink points (bottom two lines) and cultured Archaea, Bacteria, and LR White Resin. There are similar signals in all of the spectra for Amides I and II, indicating microbial cells. Image Credit: Suzuki et al. 2025.

These are photographs of a nontronite-bearing fracture in a thin section of the rock core interior (a–c) with increasing magnification. Pink and blue points represent the mineral smectite and peptides indicating microbial cells, respectively. d and e are Intensity maps of optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) spectra in a region highlighted with a yellow square in the three photographs. On the right are duplicate O-PTIR spectra of the pink points (bottom two lines) and cultured Archaea, Bacteria, and LR White Resin. There are similar signals in all of the spectra for Amides I and II, indicating microbial cells. Image Credit: Suzuki et al. 2025.

"We demonstrated our new method can detect microbes from 100-million-year-old basalt rock. But we need to extend the validity of the instrument to older basalt rock, around 2 billion years old, similar to those the Perseverance rover on Mars has already sampled," said Suzuki. "I also need to test other rock types such as carbonates, which are common on Mars and here on Earth often contain life as well. It’s an exciting time to work in this field. It might only be a matter of years before we can finally answer one of the greatest questions ever asked."

Universe Today

Universe Today