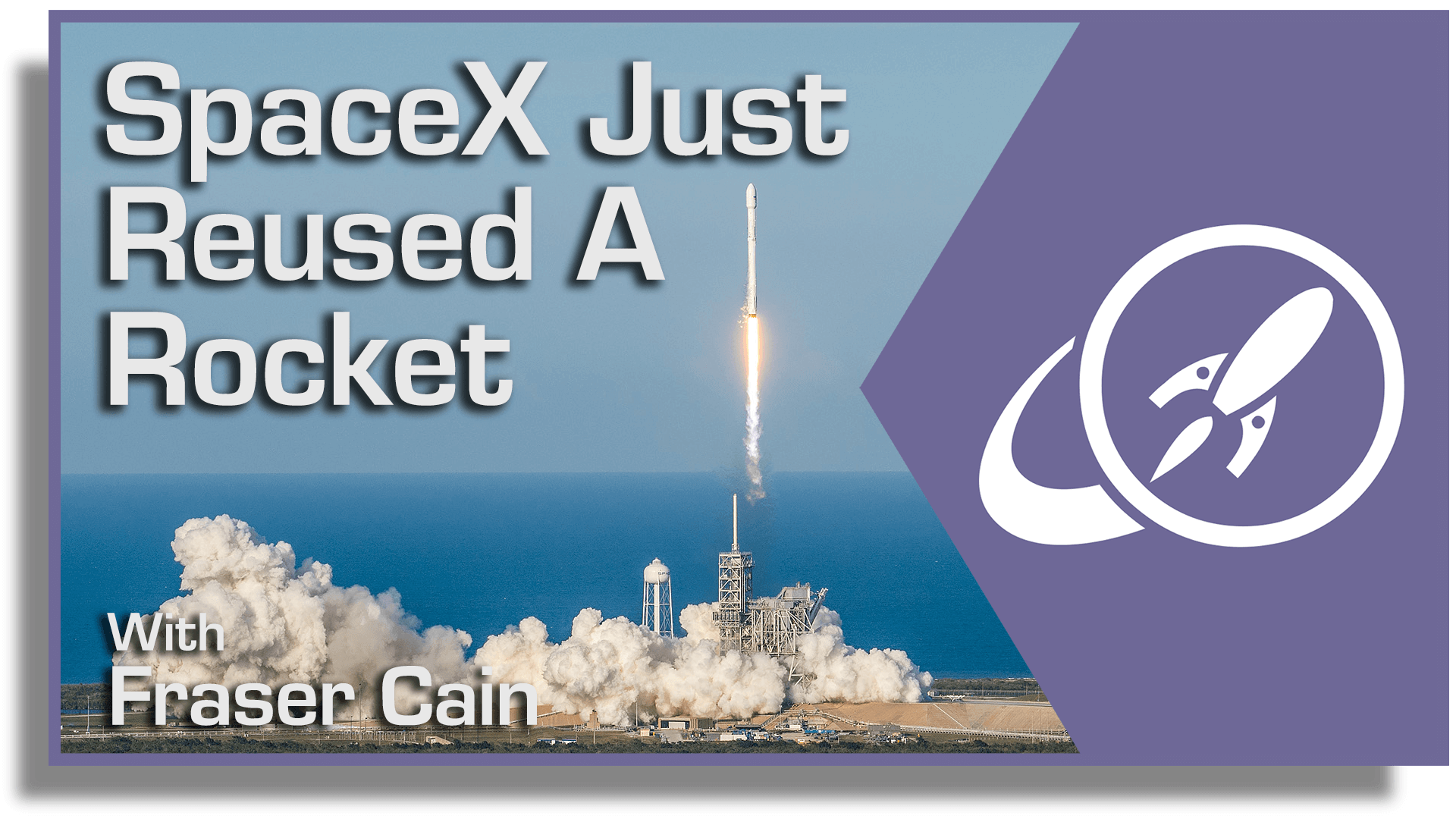

On March 30, 2017, SpaceX performed a pretty routine rocket launch. The payload was a communications satellite called SES-10, owned by a company in Luxembourg. And if all goes well, the satellite will eventually make its way to a high orbit of 35,000 km (22,000 miles) and deliver broadcasting and television services to Latin America.

For all intents and purposes, this is an absolutely normal, routine, and maybe even boring event in the space industry. Another chemical rocket blasted off another communications satellite to join the thousands of satellites that have come before.

Of course, as you probably know, this wasn’t a routine launch. It was the first step in one of the most important achievements in space flight – launch reusability. This was the second time the 14-story Falcon 9 rocket had lifted off and pushed a payload into orbit. Not Falcon 9s in general, but this specific rocket was reused.

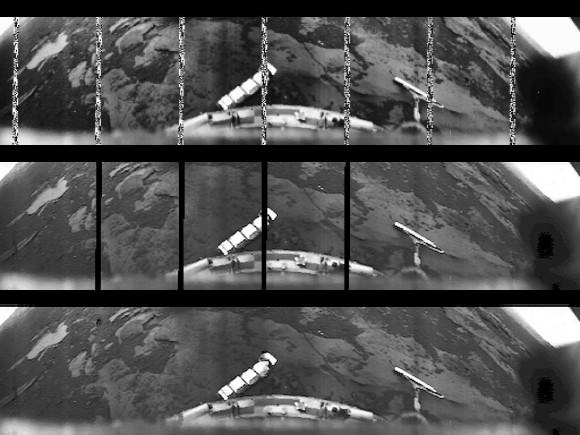

In a previous life, this booster blasted off on April 8, 2016 carrying CRS-8, SpaceX’s 8th resupply mission to the International Space Station. The rocket launched from Florida’s Cape Canaveral, released its payload, re-entered the atmosphere and returned to a floating robotic barge in the Atlantic Ocean called Of Course I Still Love You. That’s a reference to an amazing series of books by Iain M. Banks.

Why is this such an amazing accomplishment? What does the future hold for reusability? And who else is working on this?

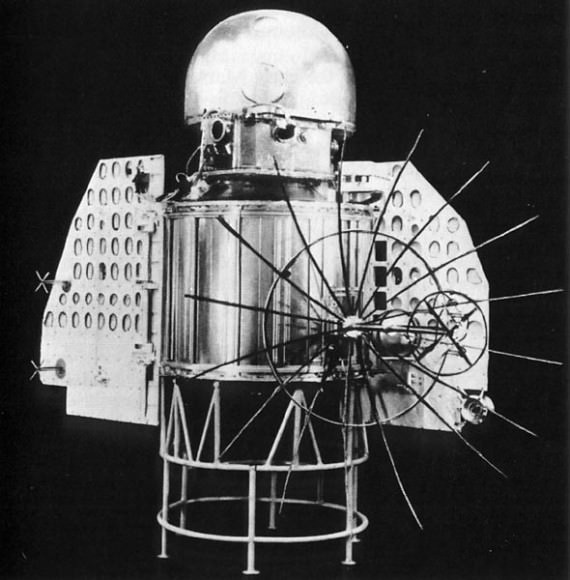

Developing a rocket that could be reused has been one of the holy grails of the space industry, and yet, many considered it an engineering accomplishment that could never be achieved. Trust me, people have tried in the past.

Portions of the space shuttle were reused – the orbiter and the solid rocket boosters. And a few decades ago, NASA tried to develop the X-33 as a single stage reusable rocket, but ultimately canceled the program.

To reuse a rocket makes total sense. It’s not like you throw out your car when you return from a road trip. You don’t destroy your transatlantic airliner when you arrive in Europe. You check it out, do a little maintenance, refuel it, fill it with passengers and then fly it again.

According to SpaceX founder Elon Musk, a brand new Falcon 9 first stage costs about $30 million. If you could perform maintenance, and then refill it with fuel, you’d bring down subsequent launches to a few hundred thousand dollars.

SpaceX is still working out what a “flight-tested” launch will cost on a reused Falcon 9 will cost, but it should turn into a significant discount on SpaceX’s already aggressive prices. If other launch providers think they’re getting undercut today, just wait until SpaceX really gets cranking with these reused rockets.

For most kinds of equipment, you want them to have been re-used many times. Cars need to be taken to the test track, airplanes are flown on many flights before passengers ever climb inside. SpaceX will have an opportunity to test out each rocket many times, figuring out where they fail, and then re-engineering those components. This makes for more durable and safer launch hardware, which I suspect is the actual goal here – safety, not cost.

In addition to the first stage, SpaceX also re-used the satellite fairing. This is the covering that makes the payload more aerodynamic while the rocket moves through the lower atmosphere. The fairing is usually ejected and burns up on re-entry, but SpaceX has figured out how to recover that too, saving a few more million.

SpaceX’s goals are even more ambitious. In addition to the first stage booster and launch fairing, SpaceX is looking to reuse the second stage booster. This is a much more complicated challenge, because the second stage is going much faster and needs to lose a lot more velocity. In late 2014, they put their plans on hold for a second stage reuse.

SpaceX’s next big milestone will be to decrease the reuse time. From almost a year to under 24 hours.

Sometime this year, SpaceX is expected to do the first launch of the Falcon Heavy. A launch system that looks like it’s made up of 3 Falcon-9 rockets bolted together. Since that’s basically what it is.

The center booster is a reinforced Falcon-9, with two additional Falcon-9s as strap-on boosters. Once the Falcon Heavy lifts off, the three boosters will detach and will individually land back on Earth, ready for reassembly and reuse. This system will be capable of carrying 54,000 kilograms into low Earth orbit. In addition, SpaceX is hoping to take the technology one more step and have the upper stage return to Earth.

Imagine it. Three boosters and upper stage and payload fairing all returning to Earth and getting reused.

And waiting in the wings, of course, is SpaceX’s huge Interplanetary Transport System, announced by Elon Musk in September of 2016. The super-heavy lift vehicle will be capable of carrying 300,000 kilograms into low Earth orbit.

For comparison, the Apollo era Saturn V could carry 140,000 kg into low Earth orbit, so this thing will be much much bigger. But unlike the Saturn V, it’ll be capable of returning to Earth, and landing on its launch pad, ready for reuse.

SpaceX just crossed a milestone, but they’re not the only player in this field.

Perhaps the biggest competitor to SpaceX comes from another internet entrepreneur: Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, the 2nd richest man in the world after Bill Gates. Bezos founded his own rocket company, Blue Origin in Seattle, which had been working in relative obscurity for the last decade. But in the last few years, they demonstrated their technology for reusable rocket flight, and laid out their plans for competing with SpaceX.

In April 2015, Blue Origin launched their New Shepard rocket on a suborbital trajectory. It went up to an altitude of about 100 km, and then came back down and landed on its launch pad again. It made a second flight in November 2015, a third flight in April 2016, and a fourth flight in June 2016.

That does sound exciting, but keep in mind that reaching 100 km in altitude requires vastly less energy than what the Spacex Falcon 9 requires. Suborbital and orbital are two totally milestones. The New Shepard will be used to carry paying tourists to the edge of space, where they can float around weightlessly in the vomit of the other passengers.

But Blue Origin isn’t done. In September 2016, they announced their plans for the follow-on New Glenn rocket. And this will compete head to head with SpaceX. Scheduled to launch by 2020, like, within 3 years or so, the New Glenn will be an absolute monster, capable of carrying 45,000 kilograms of cargo into low Earth orbit. This will be comparable to SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy or NASA’s Space Launch System.

Like the Falcon 9, the New Glenn will return to its launch pad, ready for a planned reuse of 100 flights.

A decade ago, the established United Launch Alliance – a consortium of Boeing and Lockheed-Martin – was firmly in the camp of disposable launch systems, but even they’re coming around to the competition from SpaceX. In 2014, they began an alliance with Blue Origin to develop the Vulcan rocket.

The Vulcan will be more of a traditional rocket, but some of its engines will detach in mid-flight, re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere, deploy parachutes and be recaptured by helicopters as they’re returning to the Earth. Since the engines are the most expensive part of the rocket, this will provide some cost savings.

There’s another level of reusability that’s still in the realm of science fiction: single stage to orbit. That’s where a rocket blasts off, flies to space, returns to Earth, refuels and does it all over again. There are some companies working on this, but it’ll be the topic for another episode.

Now that SpaceX has successfully launched a first stage booster for the second time, this is going to become the new normal. The rocket companies are going to be fine tuning their designs, focusing on efficiency, reliability, and turnaround time.

These changes will bring down the costs of launching payloads to orbit. That’ll mean it’s possible to launch satellites that were too expensive in the past. New scientific platforms, communications systems, and even human flights become more reasonable and commonplace.

Of course, we still need to take everything with a grain of salt. Most of what I talked about is still under development. That said, SpaceX just reused a rocket. They took a rocket that already launched a satellite, and used it to launch another satellite.

It’s a pretty exciting time, and I can’t wait to see what happens next.

Now you know how I feel about this accomplishment, I’d like to hear your thoughts. Do you think we’re at the edge of a whole new era in space exploration, or is this more of the same? Let me know your thoughts in the comments.