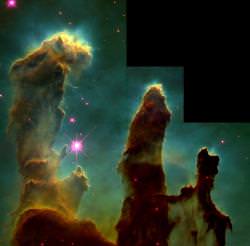

It’s time for another pretty picture. This time you’re looking at an image of the Rho Ophiuchi dark cloud, captured by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. It’s one of the closest star-forming regions to the Earth, located a mere 407 light-years away.

The nebula is mostly a large cloud of molecular hydrogen. This is the main material that all stars form from. Some gravitational event caused a cloud of this hydrogen to collapse down, condensing into vast regions of star formation.

According to recent X-ray and infrared studies, there are more than 300 newly forming stars in the central nursery. And their average age is only 300,000 years old; much younger than our own Sun’s billions of years.

The colours look nice, but that’s not what you’d actually see if you could travel to “Rho Oph”. Its colours were chosen by astronomers to clearly highlight the various temperatures and evolutionary stages of the various stars. The young stars are surrounded by disks of gas and dust, and show up as red in the image.

The extended white nebula in the centre right of the image is glowing bright in infrared radiation because of the dust there has been heated by bright young stars. The rest of the stars forming are concentrated into the filament of cold, dense gas that shows up as a dark cloud in the lower centre and left side of the image.

Original Source: Spitzer News Release