Monday, July 9 – If you’re up before dawn this morning, be sure to step outside and look at the waning Moon accompanied by ruddy Mars about 5 degrees to the south. This is definitely worth getting up early for!

Tonight we will hustle off to explore a single small globular – M80. Located about 4 degrees northwest of Antares (about two fingerwidths), this little globular cluster is a powerpunch. Located in a region heavily obscured by dark dust, M80 will shine like an unresolvable star to small binoculars and reveal itself to be one of the most heavily concentrated globulars to the telescope.

Discovered within days of each other by Messier and Méchain, respectively, in 1781, this intense Class I globular cluster is around 36,000 light-years distant. In 1860, M80 became the first globular cluster to host a nova. As stunned scientists watched, a centrally located star brightened to magnitude 7 over a period of days and became known as T Scorpii. The event then dimmed more rapidly than expected, making observers wonder exactly what they had seen.

Since most globular clusters contain stars all of relatively the same age, the hypothesis was put forward that perhaps they had witnessed an actual collision of stellar members. Given that the cluster contains more than a million stars, the probability is that some 2700 collisions of this type may have occurred during M80’s lifetime.

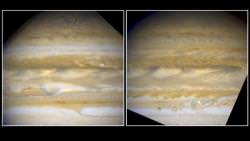

On this day in 1979, Voyager 2 quietly made its closest approach to Jupiter. How about if we take a close approach as well? Enjoy the waltz of the Galileans and all the fine details!

Tuesday, July 10 – Tonight let’s head on out towards two more giants that appear very differently from other recent studies (and from each other) – the same-field binocular pair M10 and M12.Located about half a fistwidth west of Beta Ophiuchi, M12 is the northernmost of this pair. Easily seen as two hazy round spots in binoculars, let’s go to the telescope to find out what makes M12 tick. Since this large globular is much more loosely concentrated, smaller scopes will begin to resolve individual stars from this 24,000 light-year distant Class IX cluster. Note there is a slight concentration toward the core region, but for the most part the cluster appears fairly even. Large instruments will resolve out individual chains and knots of stars.

Now let’s drop about three and a half degrees southeast and check out Class VII M10. What a difference in structure! Although they seem to be close together and close in size, the pair is actually separated by some 2,000 light-years. M10 is a much more concentrated globular showing a brighter core region to even the most modest of instruments. This compression of stars is what classifies one type of globular cluster from another, and M10 appears brighter, not because of this compression, but because it is about 2,000 light-years closer.

Wednesday, July 11 – For hard core observers, tonight’s globular cluster study will require at least a mid-aperture telescope, because we’re staying up a bit later to go for a same-low-power-field pair – NGC 6522 and NGC 6528. You will find them easily at low power just a breath northwest of Gamma Sagittarii – better known as Al Nasl – the tip of the “teapot’s” spout. Once located, switch to higher power to keep the light of Gamma out of the field and let’s do some studying.

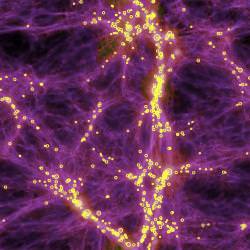

The brighter, and slightly larger, of the pair to the northeast is Class VI NGC 6522. Note its level of concentration compared to Class V NGC 6528. Both are located around 2,000 light-years away from the galactic center and seen through a very special area of the sky known as “Baade’s Window” – one of the few areas towards our galaxy’s core region not obscured by dark dust. While they are similar in concentration and distance, NGC 6522 has a slight amount of resolution towards its edges while NGC 6528 appears more random.

While both NGC 6522 and NGC 6528 were discovered by Herschel on July 24, 1784, and both are the same distance from the galactic core – they are very different. NGC 6522 has an intermediate metallicity. At its core, the red giants have been depleted – stripped tidally by evolving blue stragglers. It is possible that core collapse has already occurred. NGC 6528, however, contains one of the highest metal contents of any known globular cluster collected in its bulging core!

Thursday, July 12 – Tonight we’re going to move back toward Ophiuchus and a globular cluster unlike any that we’ve seen so far – M19. First locate Antares. About a fistwidth to the east you will see Theta Ophiuchi, with fainter star 44 to its northwest and multiple system 36 to the southeast. Move around two degrees to the west of 36 and let’s check it out.

With a visual magnitude of 6.8, this class VIII globular cluster can be seen with small binoculars, but requires a telescope to begin to take on form. Discovered by Messier in 1764, M19 is the most oblate globular known. Harlow Shapely, who studied globular clusters and cataloged their elliptical natures, estimated that there were about twice as many stars along the major axis as along the minor. This stretching of the cluster from its accepted round shape may very well have to do with its proximity to the Galactic Center – a distance of only about 5,200 light-years. This makes it only a tiny bit more remote from us than the very center of the Milky Way!

Very rich and dense, even smaller telescopes can pick up the faint blue tinge to this globular cluster. It is definitely one of the more interesting, due to its shape, but for the adventurous? There are two more. The Class VI NGC 6293 is about a degree and a half to the east-southeast and is far brighter than you might expect. It is much rounder, and is more concentrated directly in the core than its companion. Now move about a degree and a half to the north-northeast of M19 to find dimmer Class IX NGC 6284. Although it is the same size as NGC 6293, look how much more loosely this one is constructed!

Friday, July 13 – Today is Friday the 13th. If you’re not superstitious, but only having bad luck at finding some of these globular clusters – then how about if we take a look at one that’s incredibly easy to find? All you have to know is Antares and go west…

Just slightly more than a degree away you find a major globular cluster perfectly suited for every size telescope and binoculars – M4. This 5th magnitude Class IX cluster can even be spotted unaided from a dark location! In 1746 Philippe Loys de Chéseaux happened upon this 7200 light-year distant beauty – one of the nearest to us. It was also included in Lacaille’s catalog as object I.9 and in Messier’s in 1764. Much to Charles’ credit, he was the first to resolve it!

As one of the most loose, or open, globular clusters, M4 would be tremendous if we were not looking at it through a heavy cloud of interstellar dust. To binoculars, it is easy to pick out a very round, diffuse patch – yet it will begin resolution with even a small telescope. Large telescopes will also easily see a central “bar” of stellar concentration across M4’s core region, which was first noted by Herschel.

As an object of scientific study, the first millisecond pulsar was discovered within M4 in 1987 – one which is 10 times faster than the pulsar contained within the Crab Nebula. Photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1995, M4 was found to contain white dwarf stars – the oldest in our galaxy – with a planet orbiting one of them! A little more than twice the size of Jupiter, this planet is believed to be as old as the cluster itself. At 13 billion years, it would be three times the age of the Sol system!

Saturday, July 14 – Today in 1965, Mariner 4 became the first spacecraft to perform a flyby of Mars. If you’re up early, be sure to salute the Red Planet! Tonight at sunset, look for the beautiful visages of Venus and Regulus about a degree apart. Something for both the morning and evening SkyWatcher…

Tonight is New Moon and what better time to look for some alternate catalog objects? Let’s start by Herschel hunting while we continue on our globular cluster studies. Our first stop is to return to brilliant Antares and head one-half degree northwest for the Bennett list cluster NGC 6144 (RA 16 27 14.14 Dec -26 01 29.0).

Originally discovered by Herschel in 1784 and labeled as H VI.10, this 9th magnitude Class II globular is around 8500 light-years from the galactic core. While it is only about one-third the size of M4, it is also three times more distant from our solar system. If you have trouble spotting it, try high magnification to keep Antares’ glare at bay. Situated in the Rho Ophiuchi dust cloud, NGC 6144 has at least one slow variable of the RR Lyrae type.

Now drop a little more than a fistwidth south of Antares for NGC 6139 (RA 16 27 40.43 Dec -38 50 55.6). Discovered by James Dunlop in 1820 and cataloged as Dun 536, this 9th magnitude Class II globular is much further from the galactic center at a distance of 11,700 light-years. Within the gravitational pull of this low metallicity cluster, at least six RR Lyrae type variables still cling to their host.

Now that we’ve seen two very concentrated globular clusters, let’s look at one that isn’t even classed. Drop a fingerwidth south of Lambda Scorpii for NGC 6380 (RA 17 34 28.00 Dec -39 04 09.0). This 11th magnitude globular is a challenge! Also discovered by Herschel and listed as h 3688, this one is also known as Tonantzintla 1 – or Ton 1. It’s so vague that it wasn’t even classed as a globular cluster until research with a photographic plate! It’s very metal-rich and contains red giants at its bulging heart… What’s left of it!

Sunday, July 15 – Tonight while dark skies are still in our favor, let’s start off north in Hercules for a look at another globular study – M92. Although in a relatively open field for starhoppers, it’s not too hard to find if you can imagine it as the apex of a triangle with northern keystone stars – Eta and Pi – as the base.

At near magnitude 6, Class IV M92 was discovered by Johann Bode in 1777 and cataloged as Bode 76. Independently recovered by Messier in 1781 and resolved by Herschel in 1783, this bright, compact globular is around 26,700 light-years away and may be from 12-16 billion years old. It contains 14 RR Lyrae variables among its 330,000 stars, and a very rare eclipsing binary.

Viewable unaided under the right conditions and very impressive in even small binoculars, M92 is a true delight to even the smallest of telescopes. It has a very bright and unresolvable core with many outlying stars that are easily revealed. Larger scopes will appreciate its fiery appearance!

Now let’s hop south to Beta Ophiuchi to have a look at NGC 6426, about a fingerwidth south. There’s a very good reason why you’ll want to at least try with Herschel II.587! It’s even older than M92…

Discovered and cataloged by Sir William in 1786, this 11th magnitude globular Class IX globular looks destroyed in comparison. At 67,500 light-years away, it’s far more than twice the distance from us as is M92! Residing 47,600 light-years from the galactic center, NGC 6426 contains 15 RR Lyrae variables (3 of which are newly discovered) and is the most metal-poor globular known. So what’s the relation to M92? It’s even older!

Forget about finding this one in binoculars and very small telescopes. For the mid-sized scope you’ll find it conveniently located about halfway between Beta and Gamma Ophiuchi – but it’s not easy. Faint and diffuse, a large telescope is required to begin resolution.