Being stuck here on Earth, at the bottom of this enormous gravity well really sucks. The amount of energy it takes to escape into the black would make even Captain Reynolds curse up a gorram storm.

But gravity has a funny way of evening the score, giving and taking in equal measure.

There are special places in the Universe, where the forces of gravity nicely balance out. Places that a clever and ambitious Solar System spanning civilization could use to get a toehold on the exploration of the Universe.

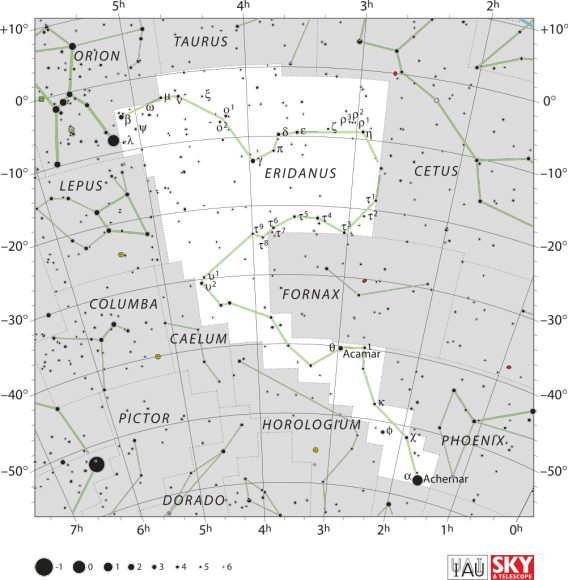

These are known as the Lagrange Points, or Lagrangian Points, or libration points, or just L-Points. They’re named after the French mathematician Joseph-Louis Lagrange, who wrote an “Essay on the Three Body Problem” in 1772. He was actually extending the mathematics of Leonhard Euler.

Euler discovered the first three Lagrangian Points, even though they’re not named after him, and then Lagrange turned up the next two.

But what are they?

When you consider the gravitational interaction between two massive objects, like the Earth and the Sun, or the Earth and the Moon, or the Death Star and Alderaan. Actually, strike that last example…

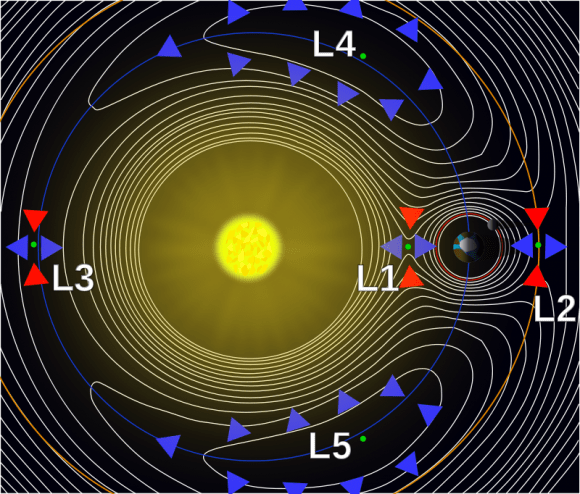

As I was saying, when you’ve got two massive objects, their gravitational forces balance out perfectly in 5 places. In each of these 5 places you could position a relatively low mass satellite, and maintain its position with very little effort.

For example, you could park a space telescope or an orbital colony, and you’d need very little, or even zero energy to maintain its position.

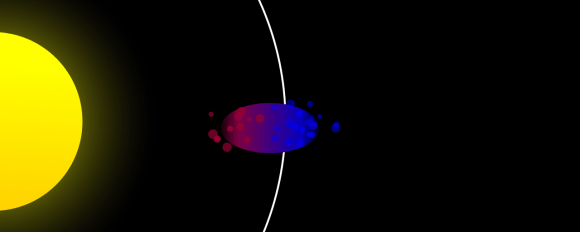

The most famous and obvious of these is L1. This is the point that’s balanced between the gravitational pull of the two objects. For example, you could position a satellite a little above the surface of the Moon. The Earth’s gravity is pulling it towards the Moon, but the Moon’s gravity is counteracting the pull of the Earth, and the satellite doesn’t need to use much fuel to maintain position.

There’s an L1 point between the Earth and the Moon, and a different spot between the Earth and the Sun, and a different spot between the Sun and Jupiter, etc. There are L1 points everywhere.

L2 is located on the same line as the mass but on the far side. So, you’d get Sun, Earth, L2 point. At this point, you’re probably wondering why the combined gravity of the two massive objects doesn’t just pull that poor satellite down to Earth.

It’s important to think about orbital trajectories. The satellite at that L2 point will be in a higher orbit and would be expected to fall behind the Earth, as it’s moving more slowly around the Sun. But the gravitational pull of the Earth pulls it forward, helping to keep it in this stable position.

You’ll want to play a lot of Kerbal Space Program to really wrap your head around it. Sadly, your No Man’s Sky time isn’t helping you at all, except to teach you that hyperdrives are notoriously finicky and you’ll never have enough inventory space.

L3 is located on the direct opposite side of the system. Again, the forces of gravity between the two masses balance out so that the third object maintains the same orbital velocity. For example, a satellite in the L3 point would always remain exactly hidden by the Sun.

Hold on, hold on, I know there are a million thoughts going through your brain right now, but bear with me.

There are two more points, the L4 and L5 points. These are located ahead and behind the lower mass object in orbit. You form an equilateral triangle between the two masses, and the third point of the triangle is the L4 point, flip the triangle upside down and there’s L5.

Now, it’s important to note that the first 3 Lagrange points are gravitationally unstable. Any satellite positioned there will eventually drift away from stability. So they need some kind of thrusters to maintain this position.

Imagine a tall smooth mountain, with a sharp peak. Put a bowling ball at the very top and you’re not going to need a lot of energy to keep it in that location. But the blowing wind will eventually knock it out of place, and down the mountain. That’s L1, L2 and L3, and it’s why we don’t see any natural objects located in those places.

But L4 and L5 are actually stable. It’s the opposite situation, a deep valley where a bowling ball will tend to fall down into. And we find asteroids in the natural L4 and L5 positions in the larger planets, like Jupiter. These are the Trojan asteroids, trapped in these natural gravity wells though the gravitational interaction of Jupiter and the Sun.

So what can we use Lagrange points for? There are all kinds of space exploration applications, and there are already a handful of satellites in the various Earth-Sun and Earth-Moon points.

Sun-Earth L1 is a great place to station a solar telescope, where it’s a little closer to the Sun, but can always communicate with us back on Earth.

The James Webb Space Telescope is destined for Sun-Earth L2, located about 1.5 million km from Earth. From here, the bright Sun, Earth and Moon are huddled up in a tiny location in the sky, leaving the rest of the Universe free for observation.

Earth-Moon L1 is a perfect place to put a lunar refueling station, a place that can get to either the Earth or the Moon with minimal fuel.

Perhaps the most science fictiony idea is to put huge rotating O’Neill Cylinder space stations at the L4 and L5 points. They’d be perfectly stable in orbit, and relatively easy to get to. They’d be the perfect places to begin the colonization of the Solar System.

Thanks gravity. Thanks for interacting in all the strange ways that you do, and creating these stepping stones that we can use as we reach up and out from our planet to become a true Solar System spanning civilization.