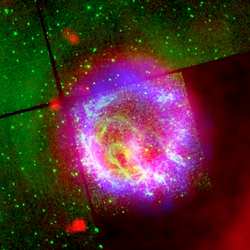

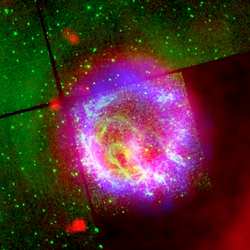

Dusty supernova remnant. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech. Click to enlarge

A supernova remnant in the Small Magellanic Cloud is only 1,000 years old; making it one of the youngest ever discovered. However, astronomers are puzzled about its strange lack of dust. Current theories about supernovae predict that it should have 100 times the dust that astronomers can detect. It’s possible that the supernova shockwaves prevented dust formation, or large amounts of colder dust just haven’t been seen by infrared instruments.

One of the youngest supernova remnants known, a glowing red ball of dust created by the explosion 1,000 years ago of a supermassive star in a nearby galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud, exhibits the same problem as exploding stars in our own galaxy: too little dust.

Recent measurements by University of California, Berkeley, astronomers using infrared cameras aboard NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope show, at most, one-hundredth the amount of dust predicted by current theories of core-collapse supernovae, barely the mass of the planets in the solar system.

The discrepancy presents a challenge to scientists trying to understand the origins of stars in the early universe, because dust produced primarily from exploding stars is believed to seed the formation of new-generation stars. While remnants of supermassive exploding stars in the Milky Way galaxy also show less dust than predicted, astronomers had hoped that supernovae in the less-evolved Small Magellanic Cloud would accord more with their models.

“Most of the previous work was focused only on our galaxy because we didn’t have enough resolution to look further away into other galaxies,” said astrophysicist Snezana Stanimirovic, a research associate at UC Berkeley. “But with Spitzer, we can obtain really high resolution observations of the Small Magellanic Cloud, which is 200,000 light years away. Because supernovae in the Small Magellanic Cloud experience conditions similar to those we expect for early galaxies, this is a unique test of dust formation in the early universe.”

Stanimirovic reports her findings in a presentation and press briefing today (Tuesday, June 6) at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Calgary, Alberta, Canada.

Stanimirovic speculates that the discrepancy between theory and observations could result from something affecting the efficiency with which heavy elements condense into dust, from a much higher rate of dust destruction in energetic supernova shock waves, or because astronomers are missing a very large amount of much colder dust that could be hidden from infrared cameras.

This finding also suggests that alternative sites of dust formation, in particular the powerful winds from massive stars, may be more important contributors to the dust pool in primordial galaxies than are supernovae.

Massive stars – that is, stars that are 10 to 40 times bigger than our sun – are thought to end their lives with a massive collapse of their cores that blows the outer layers of the stars away, spewing out heavy elements like silicon, carbon and iron in expanding spherical clouds. This dust is thought to be the source of material for the formation of a new generation of stars with more heavy elements, so-called “metals,” in addition to the much more abundant hydrogen and helium gas.

Stanimirovic and colleagues at UC Berkeley, Harvard University, the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), Boston University, and several international institutes form a collaboration called the Spitzer Survey of the Small Magellanic Cloud (S3MC). The group takes advantage of the Spitzer telescope’s unprecedented resolution to study interactions in the galaxy between massive stars, molecular dust clouds and their environment.

According to Alberto Bolatto, a research associate at UC Berkeley and principal investigator of the S3MC project, “the Small Magellanic Cloud is like a laboratory for testing dust formation in galaxies with conditions much closer to those of galaxies in the early universe.”

“Most of the radiation produced by supernova remnants is emitted in the infrared part of the spectrum,” said Bryan Gaensler of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Mass. “With Spitzer, we can finally see what these objects really look like.”

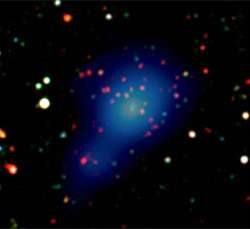

Called a dwarf irregular galaxy, the Small Magellanic Cloud and its companion, the Large Magellanic Cloud, orbit the much larger Milky Way. All three are around 13 billion years old. Over eons, the Milky Way has pushed and pulled these satellite galaxies, creating internal turbulence probably responsible for the slower rate of star formation, and thus the slowed evolution that makes the Small Magellanic Cloud look like much younger galaxies seen farther away.

“This galaxy has really had a wild past,” Stanimirovic said. Because of this, however, “the dust content and the abundance of heavy elements in the Small Magellanic Cloud are much lower than in our galaxy,” she said, “while the interstellar radiation field from stars is more intense than in the Milky Way galaxy. All these elements were present in the early universe.”

Thanks to 50 hours of observing with Spitzer’s Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) and Multiband Imaging Photometer (MIPS), the S3MC survey team imaged the central portion of the galaxy in 2005. In one piece of that image, Stanimirovic noticed a red spherical bubble that she discovered corresponded exactly with a powerful X-ray source observed previously by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory satellite. The ball turned out to be a supernova remnant, 1E0102.2-7219, much studied during the past few years in the optical, X-ray and radio bands, but never before seen in the infrared.

Infrared radiation is emitted by warm objects, and in fact, radiation from the supernova remnant, visible in only one wavelength band, indicated that the 1,000-year-old dust bubble was nearly uniformly 120 Kelvin, corresponding to 244 degrees Fahrenheit below zero. E0102, among the youngest third of all known supernova remnants, probably resulted from the explosion of a star 20 times the size of the sun, and the debris has been expanding at about 1,000 kilometers per sec (2 million miles per hour) ever since.

The infrared data provided an opportunity to see if earlier generations of stars – ones with low abundances of heavy metals – correspond more closely to current theories of dust formation in exploding supermassive stars. Unfortunately, the amount of dust – nearly one-thousandth the mass of the Sun – was at least 100 times less than predicted, similar to the situation with the well-known supernova remnant Cassiopeia A in the Milky Way.

The S3MC team plans future spectroscopic observations with the Spitzer telescope that will provide information about the chemical composition of dust grains formed in supernova explosions.

The work was sponsored by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., manages the Spitzer Space Telescope mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, based in Washington, D.C. Science operations are conducted at the Spitzer Science Center at Caltech, also in Pasadena. JPL is a division of Caltech.

Original Source: UC Berkeley News Release