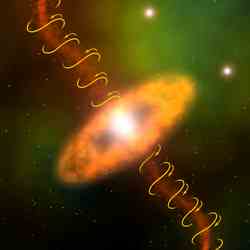

Artist’s illustration represents tightly-wound magnetic field confining jet. Image credit: NRAO/AUI/NSF. Click to enlarge

Radio astronomers have uncovered a dying star with twin jets of material confined by a powerful magnetic field. The star is located about 8,500 light-years away from Earth in the constellation of Aquila, and it’s in the process of forming a planetary nebula. Many stars like this produce elongated nebulae, where the star’s outer envelope is pushed away and channeled into tight jets. The jets come out in a corkscrew shape, which means that the star is slowly rotating.

Molecules spewed outward from a dying star are confined into narrow jets by a tightly-wound magnetic field, according to astronomers who used the National Science Foundation’s Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) radio telescope to study an old star about 8,500 light-years from Earth.

The star, called W43A, in the constellation Aquila, is in the process of forming a planetary nebula, a shell of brightly-glowing gas lit by the hot ember into which the star will collapse. In 2002, astronomers discovered that the aging star was ejecting twin jets of water molecules. That discovery was a breakthrough in understanding how many planetary nebulae are formed into elongated shapes.

“The next question was, what is keeping this outpouring of material confined into narrow jets? Theoreticians suspected magnetic fields, and we now have found the first direct evidence that a magnetic field is confining such a jet,” said Wouter Vlemmings, a Marie Curie Fellow working at the Jodrell Bank Observatory of the University of Manchester in England.

“Magnetic fields previously have been detected in jets emitted by quasars and protostars, but the evidence was not conclusive that the magnetic fields were actually confining the jets. These new VLBA observations now make that direct connection for the very first time,” Vlemmings added.

By using the VLBA to study the alignment, or polarization, of radio waves emitted by water molecules in the jets, the scientists were able to determine the strength and orientation of the magnetic field surrounding the jets.

“Our observations support recent theoretical models in which magnetically-confined jets produce the sometimes-complex shapes we see in planetary nebulae,” said Philip Diamond, also of Jodrell Bank Observatory.

During their “normal” lives, stars similar to our Sun are powered by the nuclear fusion of hydrogen atoms in their cores. As they near the end of their lives they begin to blow off their outer atmospheres and eventually collapse down to a white dwarf star about the size of Earth. Intense ultraviolet radiation from the white dwarf causes the gas thrown off earlier to glow, producing a planetary nebula. Astronomers believe that W43A is in the transition phase that will produce a planetary nebula. That transition phase, they say, is probably only a few decades old, so W43A offers the astronomers a rare opportunity to watch the process.

While the stars that produce planetary nebulae are spherical, most of the nebulae themselves are not. Instead, they show complex shapes, many elongated. The earlier discovery of jets in W43A showed one mechanism that could produce the elongated shapes. The latest observations will help scientists understand the mechanisms producing the jets.

The water molecules the scientists observed are in regions nearly 100 billion miles from the old star, where they are amplifying, or strengthening, radio waves at a frequency of 22 GHz. Such regions are called masers, because they amplify microwave radiation the same way a laser amplifies light radiation.

The earlier observations showed that the jets are coming out from the star in a corkscrew shape, indicating that whatever is squirting them out is slowly rotating.

Vlemmings and Diamond worked with Hiroshi Imai of Kagoshima University in Japan. The astronomers reported their work in the March 2 issue of the scientific journal Nature.

The VLBA is a system of ten radio-telescope antennas, each with a dish 25 meters (82 feet) in diameter and weighing 240 tons. From Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii to St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, the VLBA spans more than 5,000 miles, providing astronomers with the sharpest vision of any telescope on Earth or in space. Dedicated in 1993, the VLBA has an ability to see fine detail equivalent to being able to stand in New York and read a newspaper in Los Angeles.

The National Radio Astronomy Observatory is a facility of the National Science Foundation, operated under cooperative agreement by Associated Universities, Inc.

Original Source: NRAO News Release