Mercury on Feb. 13, 2006. Image credit: Jeffrey Beall. Click to enlarge

It’s not every day you get to see a shrinking planet. Today could be the day.

Step outside this evening at sunset and look west toward the glow of the setting sun. As the sky fades to black, a bright planet will emerge. It’s Mercury, first planet from the sun, also known as the “Incredible Shrinking Planet.”

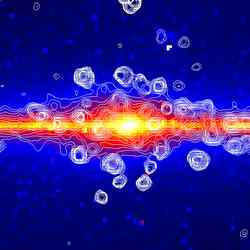

“This is only the second time in my life I’ve seen Mercury,” says sky watcher Jeffrey Beall who snapped this picture looking west from his balcony in Denver, Colorado:

Mercury is the bright “star” just above the mountain ridge, rivaling the city lights.

Mercury is elusive because it spends most of its time hidden by the glare of the sun. This week is different. From now until about March 1st, Mercury moves out of the glare and into plain view. It’s not that Mercury is genuinely farther from the sun. It just looks that way because of the Earth-sun-Mercury geometry in late February. A picture is worth a thousand words: diagram.

Friday, Feb. 24th, is the best day to look (sky map); that’s the date of greatest elongation or separation from the sun. Other dates of note are Feb 28th (sky map) and March 1st (sky map) when the crescent moon glides by Mercury??bf?very pretty.

When you see Mercury popping out of the evening twilight, you’re looking at a very strange place. “Shrinking” is a good example:

In 1974, NASA’s Mariner 10 spacecraft flew by Mercury and, for the first time, photographed the planet from close range. Cameras revealed a densely cratered world??bf?with wrinkles. Planetary geologists call them “lobate scarps” and, like wrinkles on a raisin, they are thought to be a sign of shrinking. What would make a planet shrink? One possibility: Mercury’s oversized iron core has been cooling for billions of years, and its contraction may be the driving force behind the wrinkles. No one knows for sure.

No one knows because Mercury has hardly been explored. Only one spacecraft has ever been there, and during its oh-so-brief visit Mariner 10 managed to photograph less than half (45%) of Mercury’s surface: image. The majority is terra incognita.

Another puzzle is the mystery-substance at Mercury’s poles. Radio astronomers have pinged Mercury from afar using radars on Earth, and they have found something very bright in Mercury’s polar craters. Again, no one knows what it is, although a favorite possibility is ice. Frozen water is a good reflector of radio waves and would explain the observations nicely.

How could frozen water exist on Mercury? The sun heats the planet’s surface to 400 ??bf?C (750 ??bf?F) or more, too hot for frozen anything. Yet deep down in some polar craters, researchers believe, the sun never shines. In permanent shadow, the temperature drops below -212??bf? C (-350??bf? F). Suppose a piece of an icy comet or meteorite landed in such a crater; some of the ice might survive.

Or it could be something else entirely.

What does the unknown half of Mercury look like? Is the planet really shrinking? Can ice stay frozen in an inferno? Mercury poses many questions: list. A new NASA probe named “MESSENGER” is en route to find some answers, but it will not reach Mercury until 2008.

For now, one can only peer into the twilight and wonder. Give it a try, this evening.

Original Source: NASA News Release