If the Sun, Earth and Moon are lined up, shouldn’t we get a lunar and solar eclipse every month? Clearly, we don’t, but why not?

Coincidences happen all the time. Right, Universe? One of the most amazing is that Moon and the Sun appear to be almost exactly the same size in the sky and they’re both the size of your pinky fingernail held at arm’s length. These coincidences just keep piling up. Thanks Universe?

There are two kinds of eclipses: solar and lunar. Well, there’s a third kind, but we’d best not think about that.

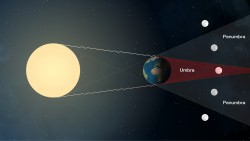

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes in between the Earth and Sun, casting a shadow down on the surface of our planet. If you’re in the path of the shadow, the Moon destroys the Sun. No, wait, I mean the Moon blocks the Sun briefly.

A lunar eclipse happens when the Moon passes through the Earth’s shadow. We see one limb of the Moon darken until the entire thing is in shadow.

You’ve got the Sun, Earth and Moon all in a line. Where they’re like this, it’s a solar eclipse, and when they’re like this, it’s a lunar eclipse.

If the Moon takes about a month to orbit the Earth, shouldn’t we get an eclipse every two weeks? First a solar eclipse, and then two weeks later, lunar eclipse, back and forth? And occasionally a total one of the heart? But we don’t get them every month, in fact, it can take months and months between eclipses of any kind.

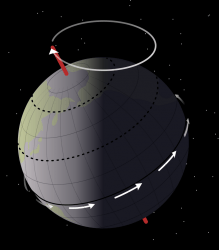

If the Sun, Earth and Moon were truly lined up perfect, this would be the case. But the reality is that they’re not lined up. The Moon is actually on an inclined plane to the Earth.

Imagine the Solar System is a flat disk, like a DVD. You kids still know what those are, right? This is the plane of the ecliptic, and all of the planets are arranged in that disk.

But the Moon is on another disk, which is inclined at an angle of 5.14 degrees. So, if you follow the orbit of the Moon as it goes around the Earth, sometimes it’s above the plane of the ecliptic and sometimes it’s below. So the shadow cast by the Moon misses the Earth, or the shadow cast by the Earth misses the Moon.

But other times, the Sun, Moon and Earth are aligned, and we get eclipses. In fact, eclipses tend to come in pairs, with a solar eclipse followed by a lunar eclipse, because everything is nicely aligned.

Wondering why the Moon turns red during a lunar eclipse? It’s the same reason we see red sunsets here on Earth – the atmosphere filters out the green to violet range of the spectrum, letting the red light pass through.

The Earth’s atmosphere refracts the sunlight so that it’s bent slightly, and can illuminate the Moon during the greatest eclipse. It’s an eerie sight, and well worth hanging around outside to watch it happen. We just had recently had a total lunar eclipse, did you get a chance to see it? Wasn’t it awesome?

Don’t forget about the total solar eclipse that’s going to be happening in August, 2017. It’s going to cross the United States from Oregon to Tennessee and should be perfect viewing for millions of people in North America. We’ve already got our road trip planned out.

Are you planning to see the 2017 eclipse? Tell us your plans in the comments below.