Mars. Image credit: Efrain Morales. Click to enlarge.

Mars. Image credit: Efrain Morales. Click to enlarge.

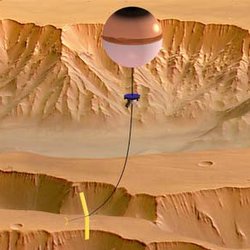

Artist illustration of a balloon floating above Mars. Image credit: ESA/Global Aerospace. Click to enlarge.

Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, have, by now, spent almost two years on the surface of Mars. They traveled several miles each, frequently stopping and analyzing scientific targets with their cameras, spectrometers and other instruments to uncover evidence of liquid water on Mars in the past. Their mission is a smashing success for NASA.

But what if NASA had a platform on Mars that was able to cover these distances in a matter of hours instead and study the rocks on the surface in the same detail as rovers do? Scientific return from such a vehicle would be immense scientists would be able to study the whole planet in greater detail in a time span of a single year.

While orbiters can look at virtually any point on the surface of a planet, they lack the resolution provided by instruments on rovers or landers. Rovers, on the other hand, have limited mobility and cannot travel very far from their landing site. As the atmosphere of Mars is very thin, an airplane at Mars would last for just an hour until it runs out of fuel.

Global Aerospace Corporation of Altadena, CA proposes that the Mars exploration vehicle combining the global reach similar to that of orbiters and high resolution observations enabled by rovers could be a balloon that can be steered in the right direction and that would drop small science packages over the target sites. The concept being developed by the Global Aerospace Corporation is funded by the NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC).

Balloons have been long recognized as unique, scientific platforms due to their relatively low cost and low power consumption. Two balloons flew in the atmosphere of Venus in 1984. In the past the inability to control the path of Mars balloons has limited their usefulness, and therefore scientific interest in their use.

Global Aerospace Corporation has designed an innovative device, called Balloon Guidance System (BGS) that enables steering a balloon through the atmosphere. The BGS is an aerodynamic surface a wing that hangs on a several kilometer-long tether below the balloon. The difference in winds at different altitudes create a relative wind at the latitude of the BGS wing, which in turn creates a lifting force. This lifting force is directed sideways and can be used to pull the balloon left or right relative to the prevailing winds.

Floating just several kilometers above the surface of Mars, the guided Mars balloons can observe rock formations, layerings in canyon walls and polar caps, and other features at very high resolution using relatively small cameras. They can be directed to fly over specific targets identified from orbital images and to deliver small surface laboratories, that will analyze the site at the level of detail rovers would do. Instruments at the balloon’s gondola can also measure traces of methane in the atmospheric and follow its increasing concentrations to the source on the ground. This way the search for existing or extinct life on Mars can be accelerated.

Original Source: NASA Astrobiology

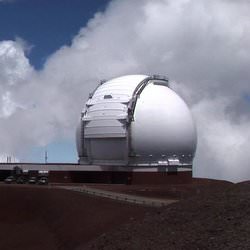

The massive Keck telescope on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. Image credit: NASA/JPL. Click to enlarge.

Are we alone in the universe? Are there planets like Earth around other ?suns? that might harbor life? Thanks to a recent technology breakthrough on a key NASA planet-finding project, the dream of answering those questions is no longer light-years away.

On a crystal clear, star-filled night at Hawaii?s Keck Observatory in Mauna Kea, NASA engineers successfully suppressed the blinding light of three stars, including the well-known Vega, by 100 times. This breakthrough will enable scientists to detect the dim dust disks around stars, where planets might be forming. Normally the disks are obscured by the glare of the starlight.

Engineers accomplished this challenging feat with the Keck Interferometer, which links the observatory?s two 10-meter (33-feet) telescopes. By combining light from the telescopes, the Keck Interferometer has a resolving power equivalent to a football-field sized telescope. The ?technological touchdown? of blocking starlight was achieved by adding an instrument called a ?nuller.?

This setup may eventually help scientists select targets for NASA?s envisioned Terrestrial Planet Finder missions. The success of those potential future missions, one observing in visible light and one in infrared, depends on being able to find Earth-like planets in the dust rings around stars.

?We have proven that the Keck Interferometer can block light from nearby stars, which will allow us to survey the amount of dust around them,? said Dr. James Fanson, project manager for the Keck Interferometer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. That survey will begin in late 2006 after the team refines the nuller?s sensitivity level.

Combined information from all of NASA?s planet-hunting missions will provide a complete picture of possible Earth-like planets: how big they are, whether they are warm enough for life, and if their atmospheres and surfaces show chemical signatures of current life.

?People have been talking about whether there are other earths out there for 2,500 years. Only now are we developing the technology to go find out,? said Michael Devirian, manager of NASA?s Navigator Program at JPL, which is investigating potential planet-exploring missions.

So far, scientists around the world have found 150 planets orbiting other stars. Most are giants, like Jupiter; none is as small as Earth. Scientists believe the best odds of finding life outside our solar system are on Earth-sized planets, particularly those with the right temperature, density and chemistry.

More information on NASA?s planet-finding missions, including the Keck Interferometer and Terrestrial Planet Finder is at http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov.

JPL manages the Keck Interferometer and the Terrestrial Planet Finder missions for NASA?s Science Mission Directorate, Washington. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. The W.M. Keck Observatory is funded by California Institute of Technology, the University of California and NASA, and is managed by the California Association for Research in Astronomy, Kamuela, Hawaii.

Original Source: NASA/JPL News Release

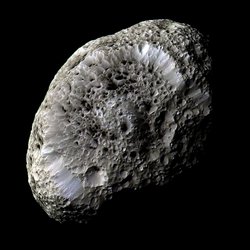

Saturn’s moon Hyperion. Image credit: NASA/JPL/SSI. Click to enlarge.

Cassini performed back-to-back flybys of Saturn moons Tethys and Hyperion last weekend, coming closer than ever before to each of them. Tethys has a scarred, ancient surface, while Hyperion is a strange, spongy-looking body with dark-floored craters that speckle its surface.

New images, mosaics and a movie of these bodies are available at http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov , http://www.nasa.gov/cassini and http://ciclops.org .

Images of Tethys taken during Cassini’s close approach to the moon on Sept. 24, 2005, reveal an icy land of steep cliffs and craters. Cassini photographed the moon’s south pole, a region not seen by NASA’s Voyager spacecraft.

A giant rift called Ithaca Chasma cuts across the disk of Tethys. Much of the topography in this region, including that of Ithaca Chasma, has been thoroughly hammered by impacts. This appearance suggests that the event that created Ithaca Chasma happened very long ago.

Near a prominent peaked crater named Telemachus are the remnants of a very old crater named Teiresias. The ancient impact site is badly overprinted and eroded by impact weathering and degradation. All that remains is a circular pattern of hummocks that mark where the old crater rim existed. Many of the fresh-appearing craters exhibit unusually bright crater floors, in contrast to the dark-floored craters seen on Saturn’s oddly tumbling moon Hyperion.

Images of Hyperion taken on Sept. 26 show a surface dotted with craters and modified by some process, not yet understood, to create a strange, “spongy” appearance, unlike the surface of any other Saturn moon.

A false-color image of Hyperion reveals crisp details and variations in color across the strange surface that might represent differences in the composition of materials. Hyperion has a notably reddish tint when viewed in natural color.

Scientists are extremely curious to learn what the dark material is that fills many craters on this moon. Features within the dark terrain, including a 200-meter-wide (650-feet) impact crater surrounded by rays and numerous bright-rimmed craters, indicate that the dark material may be only tens of meters thick with brighter material beneath.

Scientists will also be examining Cassini’s sharp views in hopes of determining whether there have been multiple episodes of landslides on Hyperion. Such “downslope” movement is evident in the filling of craters with debris and the near elimination of many craters along the steeper slopes. Answers to these questions may help solve the mystery of why this object has evolved different surface forms from other moons of Saturn.

Cassini flew by Hyperion at a distance of only 500 kilometers (310 miles). Hyperion is 266 kilometers (165 miles) across, has an irregular shape, and spins in a chaotic rotation. Much of its interior is empty space, explaining why scientists call Hyperion a rubble-pile moon. This flyby was Cassini’s only close encounter with Hyperion in the prime mission four-year tour. Over the next few months, scientists will study the data in more detail.

Cassini flew by Tethys at a distance of approximately 1,500 kilometers (930 miles) above the surface. Tethys is 1,071 kilometers (665 miles) across and will be visited again by Cassini in the summer of 2007.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.

Original Source: NASA/JPL/SSI News Release

“Snowball Earth” proponents, who say that Earth’s oceans were long ago covered by thick ice, explain the survival of life by hypothesizing the existence of small warm spots, or refugia. On the other side, supporters of a “Slushball Earth” say the planet included large areas of thin ice or open ocean, particularly around the equator.

Now, scientists who applied innovative techniques to previously unexamined rock formations have turned up strong evidence to support the “Slushball Earth” side of the decades-long scientific debate.

The study appears in the Sept. 29 online Science Express

The debate has tended to revolve around the same rock samples and analytical techniques, said Alison Olcott, an earth scientist at the University of Southern California. So she and her team focused on a drill core of little-known black shale deposits from southeastern Brazil and applied lipid biomarker techniques to identify prehistoric organisms based on the fatty remains of their cell membranes.

“This evidence for life in parts of the global oceans requires a revision of our interpretations related to this period of low-latitude glaciation,” said Enriqueta Barrera, program director in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research.

The team, which included scientists from USC, Caltech, the University of Maryland and a Brazilian mining company, identified a complex and productive microbial ecosystem, including photosynthesizing organisms that could not have existed under a thick layer of ice.

“If there were ice, it had to have been thin enough that organisms could photosynthesize below it or within it,” Olcott said.

Frank Corsetti of USC, a co-author on the study, said “this is the first real evidence that substantial photosynthesis occurred in the Earth’s oceans during the extreme ice age 700 million years ago, which is a challenge for the snowball theory.”

The evidence does not prove large parts of the ocean remained free of sheet ice during the pre-Cambrian glaciation. Although unlikely, Olcott said it is possible one of the tiny “refugia” under the “Snowball Earth” hypothesis allowed such marine life to exist.

But, she said, “finding the one anomalous spot would be quite unlikely,” adding that the samples she studied came from an extensive formation of rocks with similar characteristics.

“At what point does an enormous refugium become open ocean?” she asked.

Skeptics also may argue that the rocks do not necessarily date to a glacial era, Olcott said. But the team found evidence of glacial activity in the samples, such as dropstones (continental rocks dropped by melting glaciers into marine deposits) and glendonites (minerals that only form in near-freezing water).

“Geologists don’t necessarily think of looking for traces of microbes left in the rocks. This is the first direct look at the ecosystem during this time period,” said Olcott, who credited USC’s geobiology program, one of a handful in the country, with influencing her thinking.

Original Source: NSF News Release

Spiral Galaxy NGC 1350. Image credit: ESO. Click to enlarge.

Eighty-five million years ago on small planet Earth, dinosaurs ruled, ignorant of their soon-to-come demise in the great Jurassic extinction, while mammals were still small and shy creatures. The southern Andes of Bolivia, Chile, and Argentina were not yet formed and South America was still an island continent.

Eighty-five million years ago, our Sun and its solar system was 60,000 light years away from where it now stands [1].

Eighty-five million years ago, in another corner of the Universe, light left the beautiful spiral galaxy NGC 1350, for a journey across the universe. Part of this light was recorded at the beginning of the year 2000 AD by ESO’s Very Large Telescope, located on the 2,600m high Cerro Paranal in the Chilean Andes on planet Earth.

Astronomers classify NGC 1350 as an Sa(r) type galaxy, meaning it is a spiral with large central regions. In fact, NGC 1350 lies at the border between the broken-ring spiral type and a grand design spiral with two major outer arms. It is about 130,000 light-years across and, hence, is slightly larger than our Milky Way.

The rather faint and graceful outer arms originate at the inner main ring and can be traced for almost half a circle when they each meet the opposite arm, giving the impression of completing a second outer ring, the “eye”. The arms are given a blue tint as a result of the presence of very young and massive stars. The amount of dust, seen as small fragmented dust spirals in the central part of the galaxy and producing a fine tapestry that bear resemblance with blood vessels in the eye, is also a signature of the formation of stars.

The outer parts of the galaxy are so tenuous that many background galaxies can be seen shining through them, providing the observers with an awesome sense of depth. It is indeed quite remarkable to see that with a total exposure time of only 16 minutes, the VLT lets us admire such an incredible collection of island universes wandering about in the sky. ESO PR Photo 31b/05 is a mosaic of some of the most prominent galaxies found in the images. Some of these may reside as far as several billion light-years away, i.e. the light from these galaxies was emitted when the Sun and the Earth had not yet formed.

NGC 1350 is located in the rather inconspicuous southern Fornax (The Furnace) constellation [2]. Recessing from us at a speed of 1860 km/s [3], it is eighty-five million light-years away. It is thus most probably not a member of the Fornax cluster of galaxies, the most notable entity in the constellation, that lies about 65 million light-years away and contains the much more famous barred spiral NGC 1365. On the sky, NGC 1350 stands on the outskirts of the Fornax cluster as can be seen on this image taken with the 1m-Schmidt telescope at La Silla.

Original Source: ESO News Release

Antares-Rho Ophiuchus region. Image credit: Thomas Davis. Click to enlarge.

A distant supernova that exploded 41,000 years ago may have led to the extinction of the mammoth, according to research conducted by nuclear scientist Richard Firestone of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

Firestone, who collaborated with Arizona geologist Allen West on this study, unveiled this theory Sept. 24 at the 2nd International Conference “The World of Elephants” in Hot Springs, SD. Their theory joins the list of possible culprits responsible for the demise of mammoths, which last roamed North America roughly 13,000 years ago. Scientists have long eyed climate change, disease, or intensive hunting by humans as likely suspects.

Now, a supernova may join the lineup. Firestone and West believe that debris from a supernova explosion coalesced into low-density, comet-like objects that wreaked havoc on the solar system long ago. One such comet may have hit North America 13,000 years ago, unleashing a cataclysmic event that killed off the vast majority of mammoths and many other large North American mammals. They found evidence of this impact layer at several archaeological sites throughout North America where Clovis hunting artifacts and human-butchered mammoths have been unearthed. It has long been established that human activity ceased at these sites about 13,000 years ago, which is roughly the same time that mammoths disappeared.

They also found evidence of the supernova explosion’s initial shockwave: 34,000-year-old mammoth tusks that are peppered with tiny impact craters apparently produced by iron-rich grains traveling at an estimated 10,000 kilometers per second. These grains may have been emitted from a supernova that exploded roughly 7,000 years earlier and about 250 light years from Earth.

“Our research indicates that a 10-kilometer-wide comet, which may have been composed from the remnants of a supernova explosion, could have hit North America 13,000 years ago,” says Firestone. “This event was preceded by an intense blast of iron-rich grains that impacted the planet roughly 34,000 years ago.”

In support of the comet impact, Firestone and West found magnetic metal spherules in the sediment of nine 13,000-year-old Clovis sites in Michigan, Canada, Arizona, New Mexico and the Carolinas. Low-density carbon spherules, charcoal, and excess radioactivity were also found at these sites.

“Armed with only a magnet and a Geiger counter, we found the magnetic particles in the well-dated Clovis layer all over North America where no one had looked before,” says Firestone.

Analysis of the magnetic particles by Prompt Gamma Activation Analysis at the Budapest Reactor and by Neutron Activation Analysis at Canada’s Becquerel Laboratories revealed that they are rich in titanium, iron, manganese, vanadium, rare earth elements, thorium, and uranium. This composition is very similar to lunar igneous rocks, called KREEP, which were discovered on the moon by the Apollo astronauts, and have also been found in lunar meteorites that fell to Earth in the Middle East an estimated 10,000 years ago.

“This suggests that the Earth, moon, and the entire solar system were bombarded by similar materials, which we believe were the remnants of the supernova explosion 41,000 years ago,” says Firestone.

In addition, Berkeley Lab’s Al Smith used the Lab’s Low-Background Counting Facility to detect the radioactive isotope potassium-40 in several Clovis arrowhead fragments. Researchers at Becquerel Laboratories also found that some Clovis layer sediment samples are significantly enriched with this isotope.

“The potassium-40 in the Clovis layer is much more abundant than potassium-40 in the solar system. This isotope is formed in considerable excess in an exploding supernova, and has mostly decayed since the Earth was formed,” says Firestone. “We therefore believe that whatever hit the Earth 13,000 years ago originated from a recently exploded supernova.”

Firestone and West also uncovered evidence of an even earlier event that blasted parts of the Earth with iron-rich grains. Three mammoth tusks found in Alaska and Siberia, which were carbon-dated to be about 34,000 years old, are pitted with slightly radioactive, iron-rich impact sites caused by high-velocity grains. Because tusks are composed of dentine, which is a very hard material, these craters aren’t easily formed. In fact, tests with shotgun pellets traveling 1,000 kilometers per hour produced no penetration in the tusks. Much higher energies are needed: x-ray analysis determined that the impact depths are consistent with grains traveling at speeds approaching 10,000 kilometers per second.

“This speed is the known rate of expansion of young supernova remnants,” says Firestone.

The supernova’s one-two punch to the Earth is further corroborated by radiocarbon measurements. The timeline of physical evidence discovered at Clovis sites and in the mammoth tusks mirrors radiocarbon peaks found in Icelandic marine sediment samples that are 41,000, 34,000, and 13,000 years old. Firestone contends that these peaks, which represent radiocarbon spikes that are 150 percent, 175 percent, and 40 percent above modern levels, respectively, can only be caused by a cosmic ray-producing event such as a supernova.

“The 150 percent increase of radiocarbon found in 41,000-year-old marine sediment is consistent with a supernova exploding 250 light years away, when compared to observations of a radiocarbon increase in tree rings from the time of the nearby historical supernova SN 1006,” says Firestone.

Firestone adds that it would take 7,000 years for the supernova’s iron-rich grains to travel 250 light years to the Earth, which corresponds to the time of the next marine sediment radiocarbon spike and the dating of the 34,000-year-old mammoth tusks. The most recent sediment spike corresponds with the end of the Clovis era and the comet-like bombardment.

“It’s surprising that it works out so well,” says Firestone.

Original Source: Berkeley Labs News Release

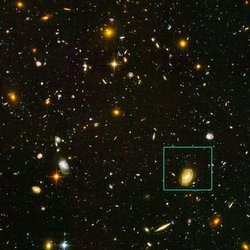

Distant galaxy in a Hubble Ultra Deep Field image. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge.

Two of NASA’s Great Observatories, the Spitzer and Hubble Space Telescopes, have teamed up to “weigh” the stars in several distant galaxies. One of these galaxies, among the most distant ever seen, appears to be unusually massive and mature for its place in the young universe.

This came as a surprise to astronomers, as the earliest galaxies in the universe are commonly thought to have been much smaller associations of stars that gradually merged to build large galaxies like our Milky Way.

“This galaxy, named HUDF-JD2, appears to have bulked up quickly, within the first few hundred million years after the big bang. It made about eight times more mass in stars than are found in our own Milky Way, and then, just as suddenly, it stopped forming new stars,” said Bahram Mobasher of the Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore and the European Space Agency, Paris.

The galaxy was pinpointed among approximately 10,000 others in a small patch of sky called the Hubble Ultra Deep Field (UDF). The galaxy is believed to be about as far away as the most distant known galaxies. It represents an era when the universe was only 800 million years old. That is about five percent of the universe’s age of 14 billion years.

Scientists studying the UDF found this galaxy in Hubble’s infrared images. They expected it to be young and small, like other known galaxies at similar distances. Instead, they found evidence the galaxy is remarkably mature and much more massive, and its stars appear to have been in place for a long time.

Hubble’s optical-light UDF image is the deepest image ever taken, yet this galaxy was not evident. This indicates much of the galaxy’s optical light has been absorbed by traveling billions of light-years through intervening hydrogen gas. The galaxy was detected using Hubble’s Near Infrared Camera and Multi-Object Spectrometer. It was also detected by an infrared camera on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) at the European Southern Observatory. At those longer infrared wavelengths, it is very faint and red.

The big surprise is how much brighter the galaxy is in even longer- wavelength infrared images from the Spitzer Space Telescope. Spitzer is sensitive to the light from older, redder stars, which should make up most of the mass in a galaxy. The infrared brightness of the galaxy suggests it is massive. “This would be quite a big galaxy even today,” said Mark Dickinson of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Ariz. “At a time when the universe was only 800 million years old, it’s positively gigantic,” he added.

Spitzer observations were also independently reported by Laurence Eyles from the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom and Haojing Yan of the Spitzer Science Center, Pasadena, Calif. They also revealed evidence for mature stars in more ordinary, less massive galaxies at similar distances, when the universe was less than one billion years old.

The new observations reported by Mobasher extend this notion of surprisingly mature “baby galaxies” to an object which is perhaps 10 times more massive, and which seemed to form its stars even earlier in the history of the universe.

Mobasher’s team estimated the distance to this galaxy by combining information provided by the Hubble, Spitzer, and VLT observations. The relative brightness of the galaxy at different wavelengths is influenced by the expanding universe and allows astronomers to estimate its distance. They can also get an idea of the make-up of the galaxy in terms of the mass and age of its stars. It will take the next generation of telescopes, such as the infrared James Webb Space Telescope, to confirm the galaxy’s distance.

While astronomers generally believe most galaxies were built piecewise by mergers of smaller galaxies, the discovery of this object suggests at least a few galaxies formed quickly long ago. For such a large galaxy, this would have been a tremendously explosive event of star birth. Mobasher’s results will appear in the Astrophysical Journal on Dec. 20.

For electronic images from the research and information on the Web, visit: http://hubblesite.org/news/2005/28

Original Source: Hubble News Release

NGC 253. Image credit: Paul Mayo. Click to enlarge.